Bruce Schneier argues that reliance on blockchain distributed ledger technology is creating a dangerous over-confidence in its security. He argues encryption can’t do it all. Somewhere there’s always going to be a man in the loop and if institution aren’t fixed then …

What blockchain does is shift some of the trust in people and institutions to trust in technology. You need to trust the cryptography, the protocols, the software, the computers and the network. And you need to trust them absolutely, because they’re often single points of failure. …In many ways, trusting technology is harder than trusting people. Would you rather trust a human legal system or the details of some computer code you don’t have the expertise to audit? …

Irrational? Maybe, but that’s how trust works. It can’t be replaced by algorithms and protocols. It’s much more social than that.

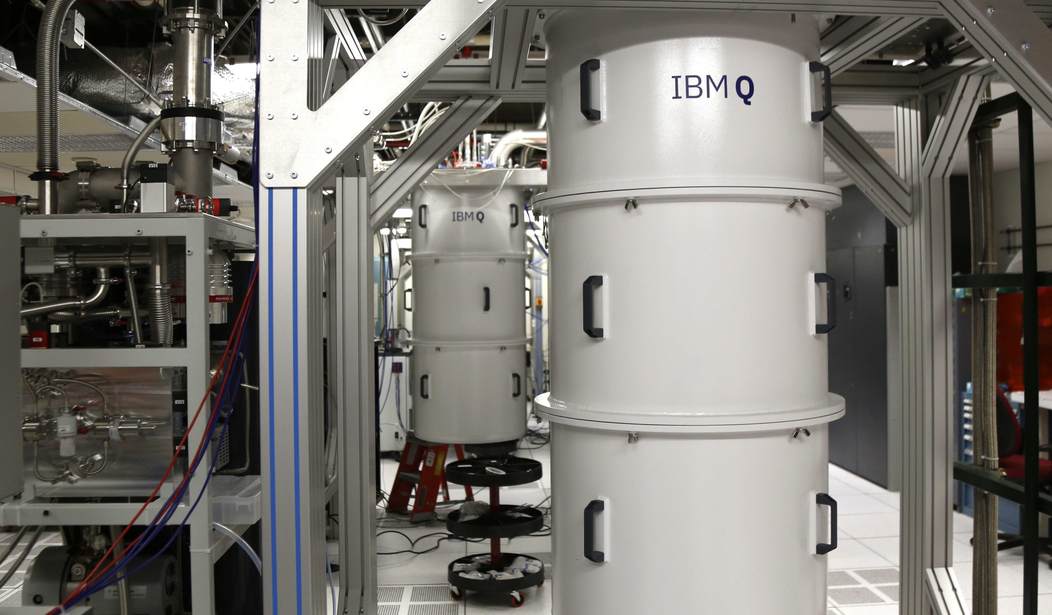

Alas institutions and social systems have proved less than trustworthy so users disillusioned with the giant centralized servers and the loss of control over their data continue to seek at least partial safety in better technology. But Schneier’s right in saying the blockchain, like many other technologies, face future threats. One of the best known threats is quantum computing which has the ability to probabilistically evaluate many situations at once. “A quantum computer with n qubits can be in an arbitrary superposition of up to 2^n different states simultaneously. This compares to a normal computer that can only be in one of these 2^n states at any one time”. This can have dramatic consequences.

Superposition lets one qubit perform two calculations at once, and if two qubits are linked through a quantum effect known as entanglement, they can help perform 2^2 or four calculations simultaneously; three qubits, 2^3 or eight calculations; and so on. In principle, a quantum computer with 300 qubits could perform more calculations in an instant than there are atoms in the visible universe. A powerful enough quantum computer could successfully break conventional cryptography, including that protecting blockchains.

This challenge is to be expected. Federov, Kiktenko and Lvovsky argue that security mass extinction events are simply part of a never-ending technological arms race. In the eternal contest between attack and defense any advantage is temporary.

Information security has faced such mass extinctions before. For example, during the Second World War, German military messages were encoded and decrypted using Enigma machines, initially giving the Axis powers an advantage until the Allies cracked the Enigma code. And in 1997, the Data Encryption Standard, an algorithm for encrypting electronic data that was then state of the art, was broken in a public contest to prove its lack of security. That gave rise to a second competition to develop a new protocol, resulting in today’s Advanced Encryption Standard. … Fortunately, quantum technologies also offer opportunities to enhance the security and performance of blockchains.

But the quantum both giveth and taketh away. “Various groups have suggested adding quantum cryptography to blockchains to guarantee their security”. But “Del Rajan and Matt Visser at the Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand … suggest making the entire blockchain a quantum phenomenon”. If technologically feasible this would create the possibility of security guaranteed by the laws of physics themselves.

Their idea is to create a blockchain using quantum particles that are entangled in time. That would allow a single quantum particle to encode the history of all its predecessors in a way that cannot be hacked without destroying it …

The phenomenon at the heart of their approach is called entanglement. When two quantum particles are entangled, they share the same existence. This happens when they interact at the same point in space and time. After that, a measurement on one immediately influences the other, no matter how far apart they may be.

What guarantees security is that entanglement is extraordinarily fragile. A measurement on one of a pair of entangled particles immediately destroys the link. So if a malicious user attempts to interfere with one of the pair, it is immediately obvious to the other.

Just as particles can become entangled across space, they can also become entangled over time. So a particle existing in the present can be entangled with one that existed in the past. And a measurement on it immediately influences its predecessor. …

This chain is secure because anybody attempting to tamper with it immediately invalidates it. That’s the advantage of quantum entanglement.

This quantum blockchain has another advantage: the earlier blocks are completely tamper-proof. “The attacker cannot even attempt to access the previous photons since they no longer exist,” say Rajan and Visser. “Entanglement in time provides a far greater security benefit than an entanglement in space.”

Mind boggling as this may sound Rajan and Visser note that “all the subcomponents of this system have already been shown to be experimentally realized.” Indeed a quantum key distribution protected by spatially entangled particles has already been in testing for some time. Despite technological difficulties there’s a good chance some of these magic bullets will wind up working to a degree.

Technology and institutions interact with each other. The blockchain’s success is not based on simple trendiness but because of its potential to help reconcile national security imperatives like CALEA while maximizing the security of personal ownership over data. This problem is particularly daunting because two seemingly contradictory interests must be served.

The U.S. Congress passed the CALEA to aid law enforcement in its effort to conduct criminal investigations requiring wiretapping of digital telephone networks. The Act obliges telecommunications companies to make it possible for law enforcement agencies to tap any phone conversations carried out over its networks, as well as making call detail records available. The act stipulates that it must not be possible for a person to detect that his or her conversation is being monitored by the respective government agency.

One of the most promising solutions to this conundrum is to create markets for personal information through the blockchain which will allow creators to retain meaningful control of their data while allowing the government to access at least part of it through a financial mechanism. Not all the kinks are worked out to be sure but are they ever?

Every technological paradigm shift never leaves us exactly as we were but always leaves us lurching a little further into the unknown. Never before have “records about past transactions [been] encoded onto a quantum state that is spread across time … current records in a quantum blockchain are not merely linked to a record of the past but rather a record in the past, one that does not exist anymore.” The blockchain doesn’t constitute a magic bullet but it does change the ammunition.

Would you rather trust a human legal system or a quantum time machine? Perhaps we should hedge our bets and mistrust both by a little.

Follow Wretchard on Twitter

For a list of books most frequently purchased by readers, visit my homepage.

Support the Belmont Club by purchasing from Amazon through the links below.

Books:

Custer’s Trials: A Life on the Frontier of a New America, by T.J. Stiles. Winner of the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in History, this book paints a portrait of Custer that demolishes historical caricature, revealing a volatile, contradictory, intense person — capable yet insecure, intelligent yet bigoted, passionate yet self-destructive, a romantic individualist at odds with the institution of the military (he was court-martialed twice in six years). The key to understanding Custer, Stiles writes, is keeping in mind that he lived on a frontier in time. In the Civil War, the West, and many other areas, Custer helped to create modern America, but could never adapt to it. Stiles casts surprising new light on a near-mythic American figure, a man both widely known and little understood.

Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, by Sebastian Junger. We have a strong instinct to belong to small groups defined by clear purpose and understanding or “tribes,” a connection now largely lost. But its pull on us remains and is exemplified by combat veterans who find themselves missing the intimate bonds of platoon life at the end of deployment and the high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder suffered by military veterans today. Combining history, psychology, and anthropology, Junger explores what we can learn from tribal societies about loyalty, belonging, and the eternal human quest for meaning. He explains why we are stronger when we come together, and how that can be achieved even in today’s divided world.

For a list of books most frequently purchased by readers, visit my homepage.

Did you know that you can purchase some of these books and pamphlets by Richard Fernandez and share them with your friends? They will receive a link in their email and it will automatically give them access to a Kindle reader on their smartphone, computer or even as a web-readable document.

The War of the Words, Understanding the crisis of the early 21st century in terms of information corruption in the financial, security and political spheres

Rebranding Christianity, or why the truth shall make you free

The Three Conjectures, reflections on terrorism and the nuclear age

Storming the Castle, why government should get small

No Way In at Amazon Kindle. Fiction. A flight into peril, flashbacks to underground action.

Storm Over the South China Sea, how China is restarting history in the Pacific

Tip Jar or Subscribe or Unsubscribe to the Belmont Club

Join the conversation as a VIP Member