More than 60 years ago, the good Sisters of Mercy taught me how to read. Like all children, I was eager to learn and quickly grasped the basic elements of reading, including sounding words out and learning phonics. It seemed natural, and even easy.

But then, the most gigantic mistake in the history of American public education was made when public schools dropped the traditional method of teaching children how to read in favor of a “whole language” approach in the 1970s. The new technique relied on the use of cues and word recognition in reading rather than decoding and phonics.

The result was an unmitigated disaster. Even before COVID saw test scores drop through the floor, the decline in reading skills appeared unstoppable.

Now educators have suddenly discovered the answer: phonics. And New York City schools are about to implement updated phonics programs that, it is hoped, will improve this vital skill for their students.

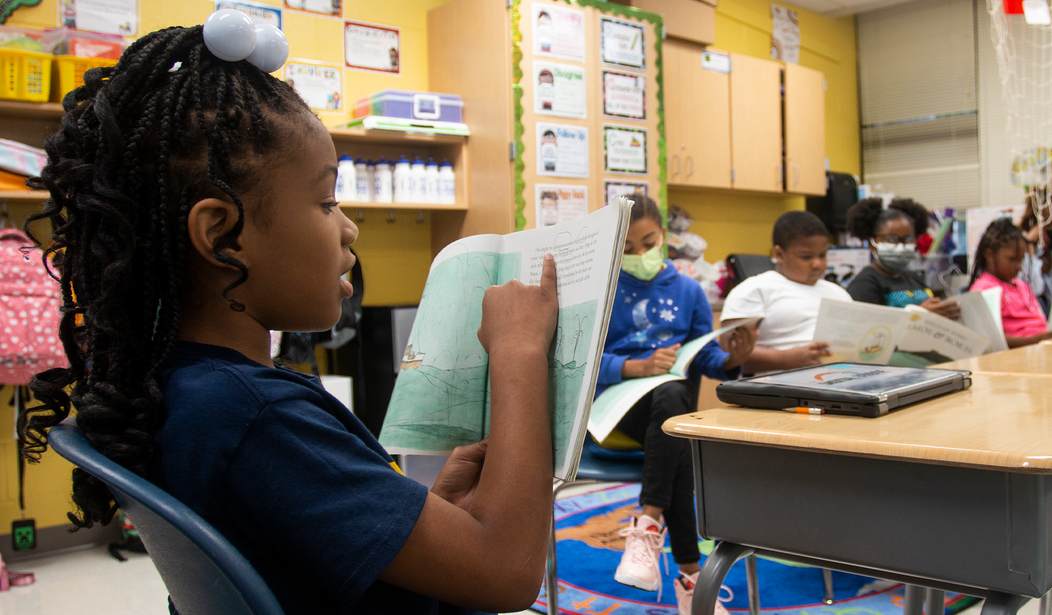

Last week, students in a first-grade class there sounded out words such as “neat” and “hippo” in a lesson led by teacher Jocelyn Testa. Sitting in a group in a corner of the classroom near a window, the children read from a book called “Joaquin’s Zoo,” as Ms. Testa helped them to decode the words.

Nine-year-old Terrance Mims, a fourth-grader, felt good about the approach. “When you sound out letters in a word, it kinda helps you pronounce it better,” he said. “You can break it down, and get a vision of how you say it.”

From the mouths of children, wisdom.

Related: Impossible: The High School Class So Popular Kids Sit In on It so They Can LEARN Stuff

Phonics isn’t the total answer. Teaching teachers is a good place to start. Many of the teachers themselves may be unfamiliar with teaching phonics since it hasn’t been formally taught since their parents were in primary school. New York Teachers Union President Michael Mulgrew thinks it’s the right decision, but what “it comes down to, is the department capable of actually implementing a training regimen that’s the same across the board, for all the schools.”

New York City Schools Chancellor David Banks says this new approach to reading will be the first time the 1-million-student district has mandated how teachers will conduct reading lessons.

“We’re all working really hard on the wrong track,” Mr. Banks, a former city teacher, and principal, said in an interview last week. “My goal is to get us back on the right track.”

The Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, based at Teachers College, Columbia University, provides professional development for a curriculum based in balanced literacy in about 150 New York City schools. The project estimates about 15% of American elementary schools use some part of the curriculum, which isn’t published by the project.

The new plan to be introduced by Mr. Banks doesn’t include the curriculum but it has been updated with a greater focus on phonics practice. “All of us have been looking for a way to learn from the science of reading without throwing the baby out with the bathwater,” said Lucy Calkins, founding director of the reading and writing project.

Very young children won’t have a problem transitioning to “the science of reading” away from the “whole language” approach. The older the child, the more difficult it might be. But any way you look at this decision, it’s likely to pay off in both the short and long term.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member