FALLUJAH, IRAQ — Captain Steve Eastin threw open the door to the Iraqi Police captain’s office and cancelled a joint American-Iraqi officer’s meeting before it could even begin. “Someone just shot at my Marines,” he said. “We can’t do this right now.”

I following him into the hall.

“What happened?” I said.

“Someone just shot at my guys at the flour mill,” he said. “A bullet struck a wall four feet over a Marine’s head. We have to go in there and extract them.”

“They don’t extract themselves?” I said.

“They’re on foot,” he said, “and we’re going in vehicles. They don’t extract themselves on foot.”

And I was getting comfortable and even bored in post-insurgent Fallujah. Complacency kills, and Fallujah isn’t completely free of insurgents just yet.

“Can I go with the extraction team?” I said.

“They’ve already left in Humvees,” he said.

But he did send a patrol to the flour mill less an hour later, and I went with them.

Captain Eastin is the commanding officer of Lima Company, and they operate in the slums of southern Fallujah. The houses down there are smaller than they are in the rest of the city, and much more decrepit. Southern Fallujah isn’t nearly as rough as a Latin American, Indian, or Egyptian shantytown, but its residents live a hardscrabble life and largely depend on charity for survival. There isn’t much of an economy. Unemployment is well over 50 percent. Many residents worked in the industrial district, but only a few factories have re-opened so far. Business owners are waiting for government compensation which was supposed to have been delivered from Baghdad months ago.

During periods of heavy fighting there were more insurgents in this part of the city than in the north, but they fought more for money than ideology. They needed the survival cash Al Qaeda paid them.

“Get your shit on!” Corporal Z bellowed at the privates under his command. He screamed at just about everyone, including me. He’s a tyrant to work underneath, and he’s a royal pain to work near. His belligerent attitude was unprofessional, and I was surprised his fellow Marines put up with him. I’m referring to him as Corporal Z instead of his full name because my objective here isn’t to name and shame him as an act of revenge.

“Are we walking or driving?” I said to him before I realized who I was dealing with.

He scowled at me like I was the dumbest human being he had ever seen.

“We don’t drive,” he said. “We walk. You got that? We walk. We don’t ever drive out of here.” He scoffed and shook his head.

Forty five minutes earlier his commanding officer Captain Eastin sent a unit to the flour mill in Humvees. Corporal Z only thought he knew what he was talking about.

As it turned out, though, we did walk. The previous patrol had been safely extracted, and the Marines didn’t want to look like they were scared.

Lieutenant Justin Lappe led the unit from the joint security station to the flour mill where the shot had been fired. We walked out the gate, and we walked quickly.

“Fuck,” Corporal Z said. “Fuck. I hope I get to shoot somebody today.”

We were in earshot of Iraqi civilians, and I hoped they didn’t understand English.

“What’s his problem, anyway?” I said to Lieutenant Lappe.

“He’s from the south side of Chicago,” he said, as if that explained it. “I guess he grew up in a really bad area. For the last five months I’ve tried to civilize him, but it can’t be done and I’ve given up.”

“How many people is he in charge of?” I said.

“You’d think he was in charge of a hundred people the way he yells at everybody,” he said. “But he’s only in charge of ten. Don’t let him get to you. We’ve all learned to ignore him. I don’t even hear him anymore.”

Corporal Z reminded me of another Marine NCO in Fallujah whom I’ll call Sergeant C. Sergeant C does not play well with others. He made it clear he hates journalists as a species and that he was going to take it out on me personally. It was nearly impossible to have anything resembling a normal conversation with him.

“When are we moving out, sergeant?” one of his men asked before rolling out on a mission.

“In a few minutes,” Sergeant C said. “Now calm down and stick your tampon back in.”

I saw him slap a private — hard — in the head in the chow hall during lunch. Any private sector employer would have fired him on the spot.

Lieutenant J.C. Davis at Camp Baharia once asked me how everybody was treating me.

“Like gold,” I said. “With one exception. I am not really getting along with Sergeant C.”

The lieutenant laughed out loud hard.

“Nobody gets along with Sergeant C,” he said.

What struck me most about Corporal Z and Sergeant C, though, is how unusual they were. I met hundreds of Marines in Fallujah, but only these two had this kind of attitude problem. Most soldiers and Marines in Iraq are far more polite and respectful of others than Americans generally.

I will not publish Corporal Z’s and Sergeant C’s names because I don’t wish to cause them any trouble, but they nevertheless violated MJT’s First Rule of Media Relations: Be nice to people who write about you for a living.

The flour mill where Marines had been shot at was only a quarter mile away, but the Marines still walked quickly and didn’t stop to talk to any Iraqis. They were much more serious and focused than usual. They knew, and I knew, that we were much more likely to be shot at this time.

An Iraqi Police station had just been constructed a few blocks from the mill, and we stopped to pick up some of their officers to take with us. I waited in the front parking lot.

The neighborhood looked terrible: shoddy houses, concrete walls, barbed wire, garbage, and rubble. I snapped a few pictures.

A poor man and his two children saw me point my camera in their general direction and decided to pose for me. They thought I wanted a picture of them. I didn’t really, but I took one anyway.

They had an innocent and kind look about them, and I felt bad that they didn’t realize that what I was really trying to photograph was their destitute neighborhood. They did not seem ashamed of their humble circumstances.

It would not have surprised me if they had. When I tried to photograph a slum in Cairo near Giza — a slum that was in much worse shape than this one — my taxi driver was embarrassed and implored me to put down my camera. He knew I was a journalist, and he wanted to protect Egypt’s dignity.

A unit of Iraqi Police officers emerged from the station with their gear on, and we walked the few remaining blocks to our destination.

The flour mill is the tallest building in the area, and I thought it looked like an ideal location for a sniper’s nest. I walked toward it in a random zigzag pattern to make myself a more difficult target.

An Iraqi Police truck roared past us on the street and nearly ran over several Marines and Iraqi Police officers. The driver slammed on the brakes. Officers jumped out with their AK-47s at the ready and merged into the staggered line of Marines.

The flour mill loomed ominously overhead. Was the earlier shot fired at the building or from the building? That wasn’t clear to me, and I dearly hoped the shot had come from somewhere else.

We made it inside the parking lot. A handful of Iraq civilians were already there talking to some Iraqi Police officers.

“Get in here! Get in here!” Corporal Z bellowed at everyone, American and Iraqi alike. “We need to shut this gate now!”

Just behind the sliding gate were the words Complacency Kills. Corporal Z, for all his faults, at least wasn’t complacent.

Once everyone was inside the parking lot, an Iraqi Police officer lackadaisically shut the gate to keep the city at bay. I assumed, then, that the shot had not come from the flour mill or we likely wouldn’t have barricaded ourselves in. Everyone seemed tense, but only slightly — except for Corporal Z who looked like he wanted to fire his weapon. I hoped his superior officers kept him away from detainees.

“Are we going inside?” I said to Lieutenant Lappe.

“I don’t know,” he said. “We need to talk to the owner, but he isn’t around. The Iraqis are trying to locate him.”

The purpose of the mission was to find him and talk to him, and also to show force. The Marines who were shot at had to be extracted, but at the same time they can’t be seen steering clear of a place just because somebody fired a round at them.

This is as much action as the Marines see any more in Fallujah, which is why the city and the rest of the province are being handed back to Iraqis.

The police could not locate the owner, so we left.

I spoke to Corporal Benjamin Smith on our walk back to the station. He had been in Fallujah before.

“I was hit more than ten times with IEDs in 2006,” he said.

“What kind of IEDs did they use out here?” I said. I was pretty sure there were no EFPs — explosively formed projectiles that tear through tanks, Humvees, and people as though they were made of wet paper. EFPs are made in Iran and are therefore supplied to Iraqi Shia militias. Fallujah is Sunni.

“155 [mm] artillery shells,” he said. “Mortar rounds. Propane tanks. P4 explosives.”

“What was Fallujah like then compared to now?” I said.

“We did a few foot patrols,” he said, “but mostly convoys. Kids even ran up to us then sometimes, but not very often. There are lots more people in the street now. Only once in a while, back then, did anyone wave. It was very rare. Typically, people who saw Marines turned their backs. It was a tough environment.”

An Iraqi Police truck roared down the street. One of the officers threw handfuls of leaflets over the side. Kids scrambled to pick them up.

The belligerent Corporal Z waded into the crowd of kids, smiled warmly, patted one on the head, and gave the others high-fives. What was this? He can’t be nice to Americans, he said he hoped he got to shoot somebody that day, but he’s affectionate with the kids?

“I like it when the kids swarm around me,” he said when he saw that I watched him. “I feel a lot safer.” This was the first time I heard him speak in a normal tone. He’s complicated.

Corporal Smith and I kept walking together.

“What’s the most intense thing you saw in Fallujah back then?”

“An SVBIED,” he said. Suicidal vehicle-borne improvised explosive device. In other words, a suicide car bomber. “It was a civilian van. It swerved right toward me, and the guy blew up himself and the van. We found pieces 150 yards away. The engine block blew 50 feet in the air and landed on a Humvee. What was left of the guy was nasty, as if he’d been drawn and quartered.”

I didn’t know what to say.

“There was another time when an SVBIED fuel tanker came at us,” he said. “Our EOF [escalation of force] measures couldn’t stop it. The driver made it into the outpost. He destroyed four Humvees and even melted one of them. No one was killed, though. Just one dead insurgent. Enemy contact was a daily occurrence then. Me and everyone I know who was here then and now are like, what the fuck? This is Fallujah? Sometimes we’ll be driving along and I’ll pass a place where I got hit. I’ll say oh fuck, this is that place where I got hit and everybody stops talking. It’s like fucking crickets in the Humvee.”

Lieutenant Lappe overheard our conversation. I think he was worried that I was getting nervous.

“No one can lay down an IED anymore without somebody calling it in,” he said.

He fished some Iraqi dinars out of his pocket, walked up the counter of a small store, and bought a huge bag of treats for the kids. It was instant kid bait.

“Chocolate! Chocolate!”

“Mister, I love you!”

“These kids are our security,” he said.

And the Marines are their security.

Kids burst out of every house on the street and formed a violent mob. They fiercely pushed, hit, kicked, and screamed at each other in a mad scramble for a small piece of candy. Someday, I thought, these children will be adults.

Lieutenant Lappe was horrified by their behavior, and he held the bag over his head and told them to calm down. They didn’t calm down. They just keep pushing and punching each other to get as close to the bag of candy as possible.

“You know what?” he said. “Fuck it.” And he threw the bag of candy up into the air over their heads. It landed in the street with a loud smack and broke open. The mob descended and it was all elbows and fists.

“Jesus,” I said.

“Yeah,” the lieutenant said. “These people have issues.”

We walked past a nice-looking Opel sedan. A Marine peered into the driver side window. Another crouched down and looked underneath.

“The Opel is like the Humvee for the muj, man,” said another.

“It’s a bad ass car,” our Iraqi-American interpreter said and grinned.

*

“There are no reporters in all of Fallujah, except Mike,” Captain Eastin said to his men when I first arrived. “So if he talks to you, talk to him. It’s the only way to get our story out.”

Soldiers and Marines tend to be a bit more friendly and trusting when I’m introduced to them in this way, and Lima Company was no exception.

I sat with a handful of jokesters in the smoke pit outside the station while First Sergeant Alonzo Baxter held court and entertained us all with his war stories and wisecracks. I can’t quote him exactly because I did not have my notebook or voice recorder with me at the time, but almost everything he said was hilarious.

“This guy ought to be famous,” one of his fellow Marines said.

“I’m famous already,” Sergeant Baxter said. “I’ve been on TV. Ain’t no thing.”

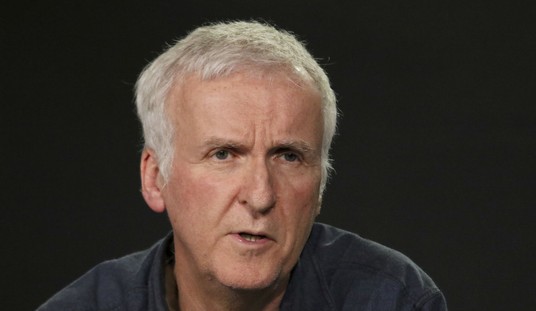

“Well, I’ll make you famous again,” I said and snapped his picture.

First Sergeant Alonzo Baxter

Lieutenant Colonel Chris Dowling paid a brief visit to the station from Camp Baharia just outside the city. He caught wind of the smoke from Sergeant Baxter’s cigar.

“What are you smoking?” Colonel Dowling said. “Is that a Cuban?”

“It’s a Cuban,” Sergeant Baxter said.

Colonel Dowling scowled at Sergeant Baxter and looked like he was gearing up to read him the riot act — or worse.

Lieutenant Colonel Chris Dowling

“You want one, sir?” Sergeant Baxter said meekly.

The colonel put his hands on his hips. Then he laughed. “Yeah,” he said. “I’ll take one.”

Sergeant Baxter handed Colonel Dowling a Cuban cigar.

“Now I get a free pass next time I mess something up,” he said.

“Oh, no you don’t,” Colonel Dowling said.

“Ah, come on, sir,” Sergeant Baxter said. “Just something small.”

The colonel then made an announcement. Secretary of the Navy Donald C. Winter was going to drop by and pay us a visit. Every Marine in the smoke pit sat bolt upright in their chairs. “So we need to get this place straightened up now.”

Five seconds later I was the only one who remained sitting. The rest were busting out brooms, organizing clutter, and taking trash to the burn pit.

No one, including the colonel, had any idea the Secretary of the Navy would be dropping by their random Joint Security Station in a rented house in the slums of Fallujah. How unlikely was that?

“Is he going to patrol?” I heard one Marine say.

“Fuck no,” said another. “That’s like President Bush going on patrol.”

Marines don’t like it when you point this out, but they are part of the Department of the Navy. They like to fashion themselves as more bad ass than the Navy, the Army, and the Air Force. They do have a point. A Marine is much more likely to see combat than a service member in any of the other branches. The Marine Corps takes far more casualties per head than the others. But the Secretary of the Navy outranked the bejeezus out of every man at that station. They found Lieutenant Colonel Dowling a little intimidating, but the news of a visit from Donald C. Winter made me think of that famous bumper sticker: Jesus is Coming. Look Busy.

Two hours later, he arrived. Lieutenant Colonel Dowling shook his hand, called him sir, and introduced him to the Marines. They stood and faced him like star struck teenagers and seemed terrified that he might find them inadequate.

He did not.

Instead he read a letter written by an Iraqi woman who wanted to thank the U.S. armed forces for freeing and protecting her country.

Each Marine was asked to briefly introduce himself. Each was given one of Donald C. Winter’s very own “unit” coins.

After the formalities, Sergeant Baxter approached the secretary with a cigar in his hand.

“Would you like one, sir?” he said. “It’s a Cuban.”

Secretary Winter happily grinned and did not even bothering putting on a show of disapproval.

“Why thank you,” he said. “I think I will.” Then he slipped the cigar into his pocket.

I quietly introduced myself to his aid Becky Brenton.

“What’s he doing this for, exactly?” I said. I doubted it was for a photo op. I was the only reporter in all of Fallujah. He crossed paths with me by sheer chance. It was obvious that he wasn’t there for any attention from me.

“He wants to thank the troops,” she said. “He does this every year. He’s on his way to Afghanistan now.”

“Well,” I said, “this is a good time for him to come to Fallujah. It’s not dangerous anymore.” I thought he might be on the dog and pony show happy tour circuit. I was wrong.

“Oh,” she said. “He’s been here before. And he was in Haditha last year.”

“Last year,” I said. “When Haditha was still hot.”

“He risked getting blown up just like everyone else,” she said.

She introduced me to him, and he was startled to see me.

“Get their stories out,” he said as he shook my hand.

“I will,” I said. “That’s why I came.”

Please support independent journalism. Traveling to and working in Iraq is expensive. I can’t publish dispatches on this Web site for free without substantial reader donations, so I’ll appreciate it if you pitch in what you can.

You can make a one-time donation through Pay Pal:

[paypal_tipjar /]

Alternately, you can now make recurring monthly payments through Pal Pal. Please consider choosing this option and help me stabilize my expense account.

[paypal_monthly /]

If you would like to donate for travel and equipment expenses and you don’t want to send money over the Internet, please consider sending a check or money order to:

Michael Totten

P.O. Box 312

Portland, OR 97207-0312

Many thanks in advance.

In the Slums of Fallujah

Advertisement

Join the conversation as a VIP Member