A common problem when making and proposing legislation is trying to figure out when something is permissible or not under the law's paradigm. If we grant permission for one thing, trying to place prohibitions later is seen as an infringement. If we prohibit another, it is oppression.

This conundrum lies at the heart of a lot of politics, especially here in the United States. We are a country that believes in freedom, but "freedom" means different things to different people. The key difference, ultimately, is a matter of "we believe people should be allowed to do this, except in these cases" versus "we believe people should not be allowed to do this, except in these cases."

Generally, it is easier to make the latter argument.

Take a look at abortion, for instance. The pro-life argument is that unborn children are valuable as living humans, and therefore it is wrong to kill them before birth. However, some are willing to make exceptions: abortion is only permissible when it is performed before the child can feel pain or has a detectable heartbeat, or if the mother's life is at stake (like in an ectopic pregnancy). You can make consistent arguments for why these exceptions exist despite generally being opposed to abortion because you believe it should be prohibited in the first place.

The pro-choice argument does not really have this luxury, because it starts with the idea that abortion is permissible. If a woman has the right to terminate a pregnancy, why would that right be denied in one case but not the other? Of course, the left doesn't actually believe there should be any restrictions on abortion, but that is the point: if something is declared a right, it should be exercised to its fullest extent.

The same line of reasoning can be applied to euthanasia: the argument against it is that determining when someone should die is not in the hands of other people. You can make very tight exceptions to this (the only one I can feasibly think of is if they are already mortally wounded and cannot be saved). By contrast, Canada defined euthanasia as a right to people who are suffering, but since anyone can say they are suffering, who are they to deny someone the right to die? (And yes, I know what they are doing in trying to recommend it to people.)

Related: SHOCK Statistic: 4.1% of Deaths in Canada Due to Government Euthanasia (MAID)

The drug issue works in a similar fashion: drugs such as cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl are harmful and should not be freely available to people. You can make exceptions for things like marijuana because it is arguably less harmful (although even that is up for debate now) or say certain drug offenses should incur less punishment than others, but the general principle is what allows those exceptions to make sense. (Arguably the problem on the left isn't that they are saying they should be legal, but the focus on lessening the severity of drug charges renders them de facto legal.)

Granted, there are cases where the issues are not so black and white, like freedom of speech or freedom of assembly. If you believe people should be allowed to say what they want or should be allowed to associate with whom they want, how do you define when this is unacceptable?

Cases like these are why legalese exists: You can say what you want unless it is actively harming other people in immediate circumstances (like yelling "fire" in a crowded theater or actively inciting violence). You can belong to whatever group you want, but if it is an entity open to the public and is turning people away for no justifiable reason, it is discrimination and therefore unacceptable (at least socially).

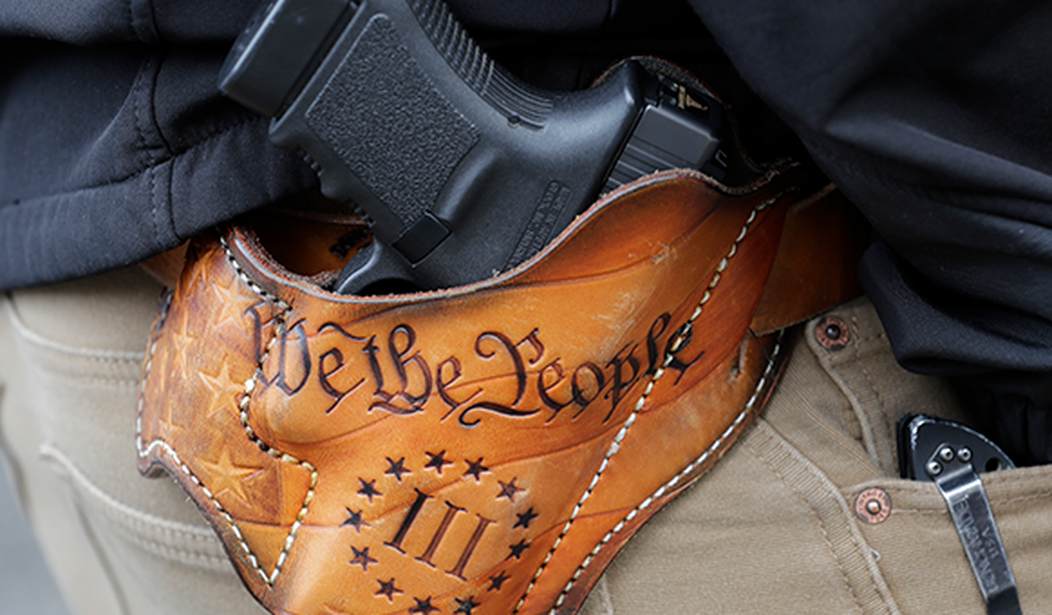

This brings us to the gun debate. The Second Amendment is explicitly written as a permission, hence it is why gun laws are viewed as an infringement by ardent defenders of gun rights, and why trying to argue in favor of gun control through this framework does not work. (Obviously, Democrats dream of removing the Second Amendment, but you knew that already.)

Related: Judge Obliterates Oregon's Newest Gun Grab

Overall, making exceptions to something prohibited is generally easier because the initial belief that it shouldn't be allowed provides a ceiling on where exceptions end. Starting from the idea that something should be permissible works as a floor, and unless you plainly define the ceiling, you end up enabling the abuse of that initial permission, whether it is by the people or the government.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member