In the first reading from this week’s Revised Common Lectionary, the Roman-backed authorities seize, beat, and imprison the evangelist Paul and his friend Silas merely for preaching and practicing their religion in the public square. (Their tormentors explain that “they are Jews and are advocating customs that are not lawful for us as Romans to adopt or observe.”)

The timing of the reading is right for a week in which the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) reported, in its annual assessment, that religious freedom has not just decreased around the world in the past year, but “has been under serious and sustained assault.” In many areas, said commission chairman Robert George, “religious freedom conditions… have spiraled downward.”

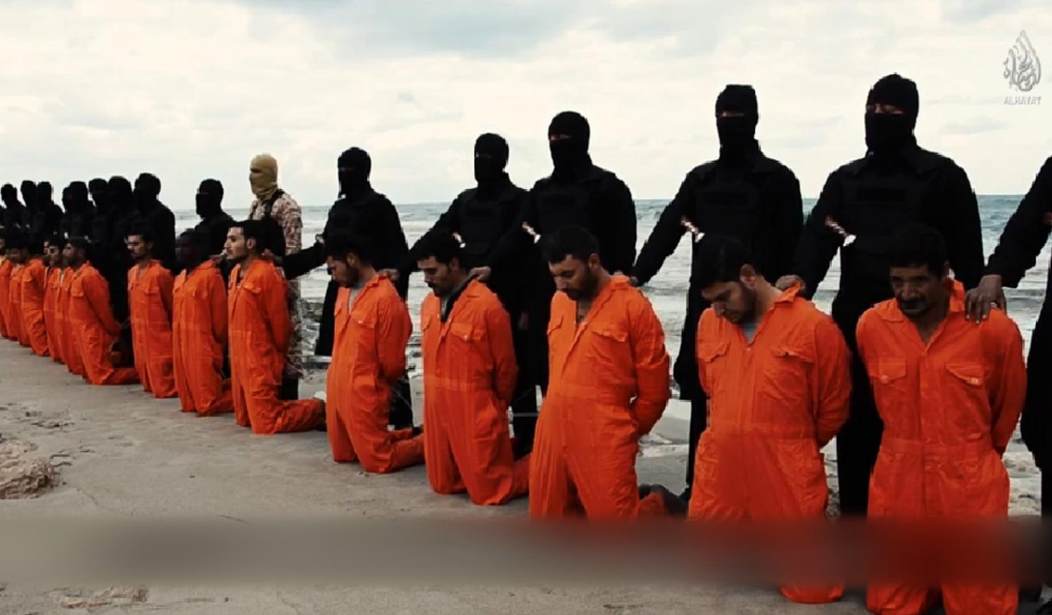

Coincidentally echoing the brutal beatings suffered by Paul and Silas, the report highlighted the “attendant suffering worldwide [resulting from diminutions of religious freedom]. The incarceration of prisoners of conscience – people whom governments hold for reasons including those related to religion – remains astonishingly widespread, occurring in country after country….”

And the report specified those abuses in page after page of appalling detail.

This is, of course, quite horrible. Some of us would argue that, minus the beatings (but not minus outrageous fines and the shuttering of innocent businesses), religious freedom is under significant attack in the United States as well. Be that as it may, both right reason and human decency should compel us to champion religious liberty at every opportunity – to cherish it, to teach the next generation about its significance, to safeguard it, and to proclaim its benefits and its central importance to a world oft-ignorant of, and sometimes hostile to, its expression and practice.

In the Judeo-Christian, Anglo-American tradition, religious liberty is, historically and in terms of importance, our “first freedom.” When Martin Luther and Desiderius Erasmus and others debated “the freedom of a Christian” during the Reformation era, the various permutations of that freedom, and their consequences, took on world-altering significance, not just in ecclesial realms, but in civic realms as well. And going back to the Magna Carta in 1215, various forms of religious liberty were the rights upon which all other British/American rights were based and built.

In fact, the very first substantive sentence of the Magna Carta (after the basic introductory salutations) reads thusly: “In the first place we grant to God and confirm by this our present charter for ourselves and our heirs in perpetuity that the English Church is to be free and to have all its rights fully and its liberties entirely.”

Similarly, the great Declaration of Arbroath of 1320, in which the Scots laid out their case for equal rights as a free people, was drafted and signed in an abbey and addressed to the Pope – for he and the church were seen as the ultimate guardians of liberty.

The first settlers to the United States – philosophical heirs to those Scots – came here primarily for the freedom to practice their various religions, with different sects or denominations setting up different settlements in Massachusetts, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island based originally on their differing sectarian beliefs. The famous Mayflower Compact of 1620, like the Magna Carta and the Declaration of Arbroath, was a documents proclaiming civic liberties under the aegis of religious freedom. And when the Virginia Declaration of Rights – the model for the Declaration of Independence – was passed in 1776, its most important advance, insisted on by a young James Madison, came in its culminating clause, saved for last in a document deliberately designed to build up to and climax in its most crucial part. That clause, the demand for religious liberty, went beyond an insistence that the state merely “tolerate” that freedom, instead proclaiming that men were by their very humanness “equally entitled to the free exercise” thereof.

And, of course, the U.S. Constitution’s very First Amendment, in its first words, forbids the government both from “establishing” a particular religion and from “prohibiting the free exercise” of the same.

Without this freedom, all other rights rapidly dissipate. Without this freedom, all of us are at risk of becoming like Paul and Silas, imprisoned and shackled – and like so many of the other poor souls around the world whose sufferings are memorialized in the USCIRF report.

Quin Hillyer is a veteran conservative columnist. He has an undergraduate degree in Theology from Georgetown University and has served for years in various forms of ecumenical lay leadership.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member