British poet Phillip Larkin famously wrote in 1967:

Sexual intercourse began

In nineteen sixty-three

(which was rather late for me) —

Between the end of the “Chatterley” ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.

Lots of people believe that recorded music also began with the Beatles, and the studio they made famous via the title of their last album, Abbey Road. Regarding the latter, not least of whom was Paul McCartney’s 53 year old daughter, Mary McCartney, before she began working on her new documentary, If These Walls Could Sing, now streaming on Disney+:

I had no idea that Abbey Road Studios had first opened 90 years ago, and when I was asked to direct this documentary, I spent the first part of the process learning all of the history, all of the artists that had gone through there. There was way too much to put into a feature documentary, but I picked the famous names like the Beatles and Pink Floyd when they did Dark Side of the Moon. I was also really happy to explore the lesser known artists like Jacqueline du Pré and peppered it with stories that I think will surprise and entertain the viewer.

The Jacqueline du Pré segment is one of the most moving of the documentary’s many vignettes. A virtuoso cellist and striking looking young woman, she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1973, which eventually robbed her of her playing ability; she passed away at age 42 in 1987.

All Those Years Ago

Abbey Road had a rich history dating back to the year it opened, 1931, long before John, Paul, George, and Ringo first walked through its doors in 1963, which Mary McCartney highlights, with clips of Edward Elgar christening the studio in 1931 by conducting the London Symphony Orchestra performing “Pomp and Circumstance March No.1,” and an interview with a spry-looking Cliff Richard, age 82. Richard’s success in England in the late ‘50s and early ’60 as a British answer to Elvis sent George Martin looking for a Cliff Richard of his own, which led to Martin signing an obscure but enthusiastic young Liverpool band in 1962. (You probably know the basics of how that story turned out.)

Regarding the early days of Abbey Road, Kevin Ryan and Brian Kehew, the authors of the brilliant 2006 book Recording the Beatles wrote:

The beautiful neighbourhood of St. John’s Wood seems, even today, a rather unlikely spot for the construction of such a studio. But it was in this upper class section of north London that the Gramophone Company found the ideal spot for its new recording complex. Originally built in 1830, No. 3 Abbey Road was an elegant, sixteen-roomed, three story residence situated just a few blocks West of Regent’s Park. The real allure of the location however, lay in the extensive 250-foot garden space that stretched deep into the lot beyond the house. The Company realized that the residence and its associated 22,750 square feet lot would be the perfect site for their proposed flagship studio, and they purchased the house in 1929 for the sum of £16,500. In the course of the ensuing construction, the house and gardens of No.5 Abbey Road would be purchased as well.

* * * * * * * *

The interior of the house itself was thoroughly renovated to provide office space and listening rooms, but existing regulations forbade alterations to its exterior. The architects were, however, free to add on to the rear of the building, and did so by constructing an enormous four-story complex over the garden that had existed on the rear lot. This rear addition attached to the house at a slight angle and contained three new studios of varying sizes, as well as various listening rooms, editing rooms, cutting rooms and workshops. The view from the street gave little indication of the magnitude of this structure, and even today, visitors arriving at the studio are surprised to find what appears to be little more than an austere and unexpectedly modest residential building only upon entering the building does one fully grasp just how much lies behind that staid façade.

The above information is condensed into a narrator speaking in painfully enunciated Received Pronunciation over the footage of Elgar, likely recorded for the documentary given all of its expository information, but treated to sound like a newsreel recording from the 1930s.

The Final Cut

From its opening day, Abbey Road consisted of three primary studios: Studio One, a huge (57 feet by 94 feet with an 40-foot tall ceiling ) facility for the recording of up to a 100-piece orchestra. Studio Two (60’ by 37’ with a 28’ ceiling) for swing-era big bands and large chamber ensembles. And Studio Three (32’ by 40’ with a 16’ ceiling) originally built to record “solo piano or small chamber groups” according to Recording the Beatles.

Studio Two was where the Beatles recorded many of their albums. Studio Three, while also occasionally used by the Beatles, was where Pink Floyd recorded Dark Side of the Moon in 1972.

By the late-1970s, the cavernous Studio One was in danger of being cut up into smaller studios or even torn down to expand the studio’s parking lot. But scoring movies (with John Williams’ legendary Raiders of the Lost Ark score being one of the first in 1981) turned out to be its salvation, Abbey Road’s Mirek Stiles wrote in 2020:

Studio One is one of the largest purpose-built studios in the world, and certainly largest of the three main recording areas at Abbey Road. It was designed predominantly with classical music in mind and, for a large proportion of the room’s early life, it was a busy place hosting the greats like Sergei Prokofiev, Yehudi Menuhin and Pablo Casals. Non-classical popular artists like Fats Waller, Glenn Miller and Burt Bacharach also graced the cavernous room with their presence, but by the middle of the 1970s problems started to creek in, major problems… [ellipses in original — Ed]

By the mid ‘70s the classical scene, from a recording point of view, had started to dry up a little. Most of the repertoire had been recorded and released on everything from vinyl to 8 track cartridges; all recorded, edited and mastered on wonderful analogue tape machines. There wasn’t a huge amount of new classical music coming through the doors and the glorious digital age was yet to explode, in which all the repertoire would be re-recorded, but this time without hiss. Unfortunately, during this lull use of Studio One with its rather large footprint was depleting rather rapidly, to the point where the suits on the EMI board wanted to know why revenues were down and what the hell was going on? This created a huge amount of pressure for then studio manager Ken Townsend. Instead of the LSO or RPO creating beautiful lush symphonic sounds, the room was becoming accustom to games of 5-a-side football and members of staff driving their cars in to the studio floor for a quick mechanical tune up. As much as the exciting game of footie between Pink Floyd and the Technical Team must have been, it wasn’t paying the bills and this had become a serious problem, serious to the point that major and in some cases drastic plans were bubbling away in the background.

As Mary McCartney adds:

I didn’t realize the impact that movie soundtracks had on Abbey Road’s history. All of these incredible movie soundtracks have been done at Abbey Road. It had Star Wars [beginning with 1983’s Return of the Jedi — Ed]. It had Indiana Jones. It had all of the Harry Potter films. The list goes on. Even to this day, film soundtracks are being done there.

One of the great storylines from the documentary is about the contract that brought film scores to Abbey Road and saved the studio to a degree. Studio 1, which was a big studio for orchestras, had been originally used for recording all of the classical music. But when those recordings started to dry up, they were like, ‘Well, what are we going to do with this huge studio?’ And they were literally looking at plans to make it into a car park or break it up into other studios. So, very timely, Ken Townsend, the manager, heard that Denham Studios was closing and got in touch with them and said, ‘Come to Abbey Road.’ They then made this contact and quickly pivoted put in a screen. To this day, it’s the leading studio for film soundtracks. You could do a whole documentary of just all of the film scores that have been done there.

Orchestral sessions for film theme songs were recorded in Studio One long before the 1980s, though. Jimmy Page appears midway through the documentary to discuss his playing acoustic rhythm guitar as a session musician on Shirley Bassey’s 1964 title track for Goldfinger. While he mentions Bassey nearly passing out after sustaining the very long last note of the song, “He loves gooooooooooooooooooldddd!!!!!!!”, he omits a detail of the story that fellow session guitarist Vick Flick once told:

Vic Flick was one of the guitarists on the session — as, purportedly, were Jimmy Page and Big Jim Sullivan — and he recalled how the singer quite literally gave herself a little more breathing room.

“Barry wanted this long note held,” he told the Daily Mail. “He said to do it again and she said she couldn’t. But then there was a rustling noise, and suddenly this bra comes over the top of the vocal booth. And then Shirley really let it go.”

Us and Them

But Abbey Road isn’t just a series of rooms. The studio always had extremely talented producers and engineers inhabiting its facilities. Before he recorded the Beatles, George Martin had already produced Judy Garland, and comedy records by Peter Sellers, Spike Milligan, Dudley Moore, and Peter Cook. The Beatles’ first engineer, Norman “Hurricane” Smith would go on to produce the early records of Pink Floyd, and then have his own career as a pop singer in the 1970s, appearing in 1973 on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. His successor engineering the Beatles, Geoff Emerick, single-handedly invented modern recording methods on the Beatles’ 1966 album, Revolver, by close-miking Ringo’s drum kit, and using hard compression techniques to give the band a new “in your face” sound and immediacy. Alan Parsons, one of the Beatles’ last engineers, would go on to engineer Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, and lead his own eponymous progressive rock group. Sadly, these engineers aren’t discussed in the documentary.

The four Beatles had mixed emotions about Abbey Road Studios. Paul loved it so much that when he wasn’t able to book the studio to complete Back to the Egg in 1978, he had an exact replica of Studio Two built in the basement of his Soho office building. Once John moved to America in the early 1970s, most of his solo albums were recorded in L.A. and New York. George complained in interviews about the studios’ sterile atmosphere and drab white walls. During a recent promotional event for If These Walls Could Sing, when asked what his favorite memory of Abbey Road Studios was, he replied, “Leaving.” As Geoff Emerick wrote in his 2006 autobiography, after the Beatles shot the famous cover photo for their swan song, “they all seemed to want a shot of them walking away from the studio, not toward it. That’s how much they had come to dislike being there.”

Unfortunately, in If These Walls, while Mary McCartney mentions film scoring saving Studio One, there’s no discussion of the 2010 stories of Abbey Road possibly going up for sale; so many legendary studios in major cities in the US and England have in recent years been scrapped to become much more lucrative apartment and condo towers. Fortunately, as Wikipedia notes, Abbey Road was spared this fate:

On 21 February 2010, EMI stated it planned to keep the studio and was looking for an investor to help finance a “revitalization” project. Meanwhile, the British government declared Abbey Road Studios a Grade II listed building which protected it from major alteration. The following December, the pedestrian crossing at Abbey Road was listed on the National Heritage List.

* * * * * * * *

In September 2012, with the takeover of EMI, the studio became the property of Universal Music. It was not one of the entities that were sold to Warner Music as part of Parlophone and instead the control of Abbey Road Studios Ltd was transferred to Virgin Records.

If These Walls debuted at the Telluride Film Festival in September. The concluding segment features an extended look at Kanye West’s recording sessions in Studio One in 2005. Given his recent anti-Semitic meltdowns, I suspect that if the film debuted in the theater this month as opposed to Disney+, these scenes would have been significantly trimmed, if not excised all together. I did laugh out loud when West mentioned that recording at Abbey Road is “something that all musicians and rappers aspire to.” Never the Twain shall meet? Well, perhaps very infrequently. And as Robert Daniels writes at Roger Ebert.com:

Especially when most music aficionados are probably keenly interested in the overall history of this studio: What makes Abbey Road so unique? Why did so many artists choose these surroundings to record some of the greatest pop music ever?

The answers come in fits and starts. We meet the studio’s longtime technician Lester Smith, an intriguing lynchpin in the day-to-day happenings of the space, but that only makes the absence of more people involved with the upkeep of Abbey Road even more glaring. John Williams also appears to discuss recording the soundtracks to “Indiana Jones” and “Star Wars” there. His explanation of the room’s unique reverb, setting this studio apart from all others, is the closest we get to someone not talking about being in the space during some famous event but absorbing the area.

That shortcoming doesn’t make those stories—Jimmy Page recording “Goldfinger” or Pink Floyd composing “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” in an adjacent studio while the Beatles were making Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band—any less awe-inspiring. But it does restrict audiences from learning a few facts that couldn’t easily be found in a biography or Wikipedia page. McCartney also struggles to anchor these recollections to the story of Abbey Road. For instance, the inclusion of cellist [Jacqueline du Pré] is an imperative chapter in the studio’s story. Unfortunately, McCartney makes [du Pré] a bespoke element rather than a fully integrated thread in the fabric of said history through some odd narrative editing choices.

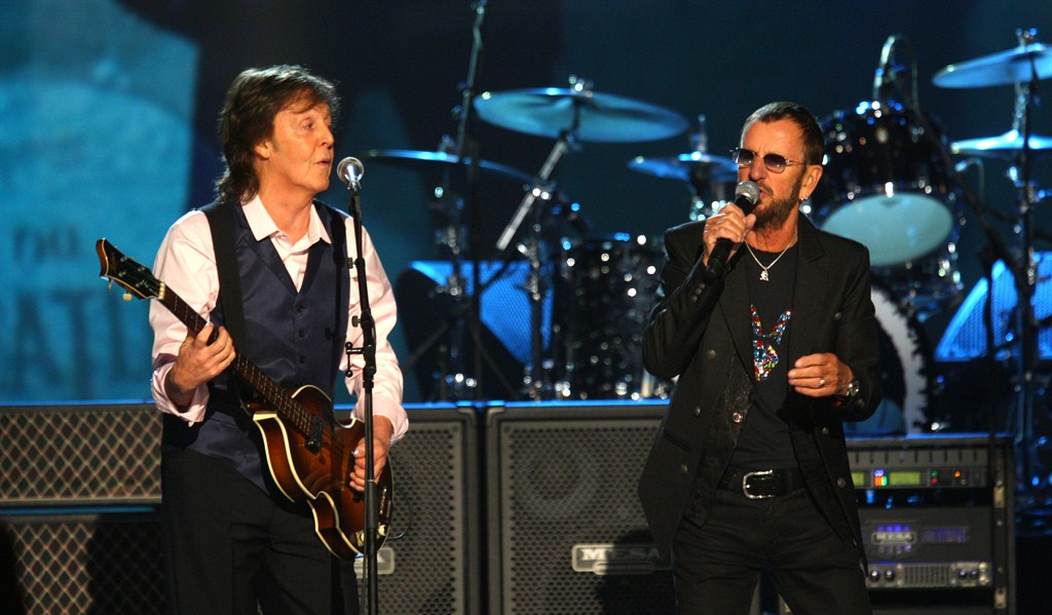

Still though, Kanye notwithstanding, with its numerous interviews with Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, Giles Martin, and audio from his late father; Elton John; plus Pink Floyd’s Roger Waters, David Gilmour, and Nick Mason, for fans of British rock, If These Walls Could Sing will be quite an enjoyable documentary.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member