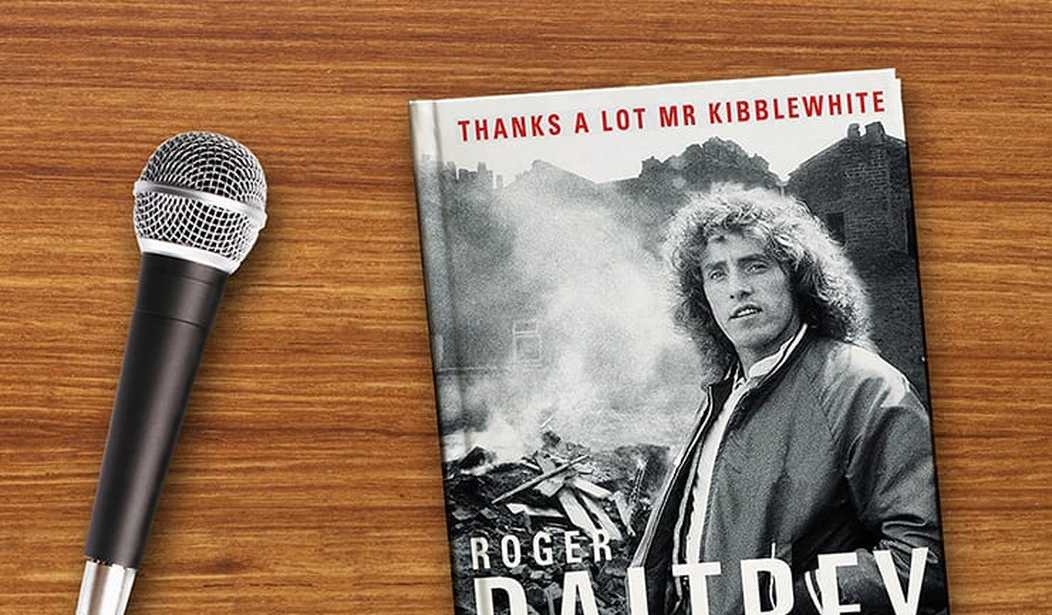

Roger Daltrey’s new autobiography, Thanks a Lot Mr. Kibblewhite (we’ll explain the title in a moment), is a fun read, but if you’re as diehard a fan of The Who as I am, you can’t help but notice it contains a few missed opportunities. Daltrey is the lead singer for one of the most influential rock bands of the 1960s through the early 1980s, yet fails to comment on some of his group’s most important moments.

But he does discuss some of the many squabbles that involved him, his band mates, and his managers. As Dave Marsh wrote in Before I Get Old, his excellent 1983 history of the band, completed immediately after their “first” farewell tour:

If the music world [of the 1960s] could be compared to a neighborhood, then the Who were the one family in every block who simply cannot keep their squabbles private, who make a mess that dangles out of the windows and into the yard and who unashamedly tangle with one another publicly in ways that mortify the neighbors. The Beatles might have argued among themselves as much as the Who, but they were discreet. The Stones were scruffier by far, but their very essence was never losing their cool. The Who battled it out right in public.

Daltrey punctuated a few of those arguments with his fists – most notoriously, an October 1973 argument with The Who’s songwriter, guitarist, and resident genius Pete Townshend, while shooting a promotional film clip during a rehearsal for the British leg of the world tour to promote their then-new album Quadrophenia:

Pete, fueled by the best part of a bottle of brandy, went off like a firecracker. He was up in my face, prodding me. “You’ll do what you’re fucking well told,” he sneered. This is not the way to talk to me, but I still backed off. The roadies knew what I was capable of so they sprang into action and held me back.

“Let him go!” screamed Pete. “I’ll kill the little fucker.” They let me go.

Next thing I knew, he’d swung a twenty-four-pound [sic] Les Paul guitar at me. [Actually, even the heaviest Les Pauls of the 1970s weighed about half that – Ed.] It whistled past my ear and glanced off my shoulder, very nearly bringing a much earlier end to The Who. I still hadn’t retaliated, but I was beginning to feel quite put out. He’d called me a little fucker, after all.

Finally, after almost ten years of Peaceful Perce, after another left hook narrowly dodged, I replied with an uppercut to the jaw. Pete went up and backward like he’d been poleaxed. And then he fell down hard, cracking his head on the stage. I thought I’d killed him.

To make matters only slightly worse, our publicist Keith Altham chose that moment to bring the American managing director from our newly signed record company onto the sound stage. The bigwig’s first sight of his big new signing was of the lead vocalist knocking the lead guitarist out cold. “My God,” said the horrified MD. “Is it always like this?”

“No,” said Keith. “Today is one of their better days.”

Mr. Kibblewhite Lights a Fire

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. The band that would become The Who began in 1961 as the Detours, when Roger Daltrey, then age 17, talked bassist John Entwistle into joining his group. A few months later, guitarist Pete Townshend would join. During that period, Doug Sandom, a decade older than the rest of the members of the Detours, served as their drummer. He would leave the band in 1964, and be replaced by the now legendary Keith Moon, then age 18.

All during this time, Daltrey was driven by a statement from his headmaster at Acton County Grammar School, Mr. Kibblewhite, who told him on his 15th birthday that “you’ll never make anything of your life, Daltrey,” after expelling him for truancy. Determined to escape his lower-middle class existence in the west London district of Acton, Daltrey was driven to be the lead singer of a rock and roll group. What he couldn’t know is that he had stumbled into the rock and roll group, one of the most influential bands of the 1960s and 1970s.

Later in 1964, The Who were discovered by wannabe filmmakers turned rock impresarios Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, when they stumbled into London’s Railway Hotel wanting to making a documentary about the then-burgeoning London “mod” scene, coming across one of the mods’ favorite bands, The Who. Lambert and Stamp decided instead to manage the group, which quickly rose to prominence in first England and eventually America on the backs of several key elements, not least of which were brilliant songs, written by Townshend, a group with four very distinct personalities, and a powerful stage show, culminating in Townshend and Moon “destroying” their equipment. (In reality, after most shows, Townshend’s guitar, at least when he played a rugged Fender Telecaster or Stratocaster, could usually be repaired, and Moon’s seemingly smashed-up drum kit was recovered by his roadie and reassembled for the next night’s gig.)

How Tommy Transformed Daltrey’s Singing

Right next to the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction,” The Who’s first album contained one of the great anthems of 1960s rebellion, “My Generation,” and its infamous line “I hope I die before I get old.” As they got older, both Townshend and Daltrey would be asked endlessly about that line, and what it was like to write it and sing it, respectively. In his 1999 book, Pete Townshend: The Minstrel’s Dilemma, Larry David Smith quotes Townshend saying in 1989, “It’s a masterpiece of a statement and there’s nothing more to be said. I certainly don’t have to live by it. It will end up in one of the future editions of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, and that’s all I care about at this stage. It’s got a life of its own.” Smith himself writes, “Few popular music lyrics have attained the mythical status of that one, simple line.” Keith Moon and John Entwistle would live out that one simple line, but Daltrey at age 74 and Townshend at 73 keep going back out on the road under the banner of The Who. In terms of chronological age, they have gotten old – and yet they still deliver an awe-inspiring performance in a band that isn’t the original Who, but still flies their flag.

However, Daltrey’s vocals at the start of the band were hardly awe-inspiring. Listening to the 1965 album that contained “My Generation,” it’s painfully obvious in retrospect that Daltrey’s singing ability isn’t quite “there” yet. While The Who billed themselves during this period on their classic promotional poster (I have a framed copy) as “Maximum R&B,” Daltrey’s singing on many songs sounds like a bad James Brown pastiche, right down to a somewhat embarrassing cover of Brown’s “Please, Please, Please.” Fortunately, to the best of my knowledge, The Who never tried to imitate Brown’s show-stopping cape routine when they played it live.

In 1968, Townshend became obsessed with the Indian mystic Meher Baba, whose teachings would influence Townshend’s songs for the rest of his time as an active songwriter. However, in Thanks a Lot Mr. Kibblewhite, Daltrey never discusses what he thought of Townshend’s obsession over Baba, or what the other members of the band thought of it. (According to rock author Richie Unterberger in his 2011 book, Won’t Get Fooled Again: The Who from Lifehouse to Quadrophenia, not surprisingly, the manic hard-partying Keith Moon didn’t think much of Townshend’s newfound faith. At one point during the band’s 1972 American tour, when Townshend was in a near paralytic rapture after visiting the Baba center in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, Moon taunted Townshend with Baba’s credo, which in 1988 would inspire the title of the hit song by singer Bobby McFerrin, “Don’t Worry, Be Happy:” “‘Be Happy,’ Keith kept chanting, exultant, flinging it out like a scarlet rag. ‘Don’t worry, be happy, don’t worry, be happy.’ Pete made no response. Just sat there and continued to suffer.”)

Meher Baba’s teachings would directly influence the lyrics of Tommy, The Who’s breakthrough 1969 “rock opera,” which catapulted them to superstardom. Tommy and the rehearsals for the tour to promote it would have a powerful influence on Daltrey’s singing, as he writes:

It was only when we took it out live that I really got to grips with where I could go with my voice. We rehearsed it at the Southall Community Centre in March 1969 and, by the fourth run-through, we’d worked it out. It was a live stage show and I felt like I’d been set free. Everything I learned to do with my voice came from Tommy, and it happened in those four rehearsals. I just hanged. It was always in my voice. I’d been getting there with Pete’s earlier songs but Tommy brought it out like that.

Did You Steal My Money?

The success of Tommy would culminate in The Who playing at Woodstock, and arguably stealing its Warner Brothers documentary movie. While the public assumed that the members of The Who were simply printing money at this point in their career, one of the most intriguing passages of Thanks a Lot Mr. Kibblewhite involves the band’s tenuous economics in the early to mid 1970s. As Daltrey writes:

We were in good shape. And then our accountant called a meeting. He said we’d had a fantastic year, which is what you want to hear from your accountant. He said we’d done all that touring, we’d done Who’s Next and Live at Leeds. We’d made loads of money. And he was pleased to tell us that we were only six hundred thousand pounds in debt.

The band’s finances were being bled dry by Lambert and Stamp becoming raging cocaine and heroin addicts by the early 1970s. After Daltrey audited The Who’s books, he convinced his bandmates to replace Lambert and Stamp with Bill Curbishley, who Daltrey notes resided “at her majesty’s pleasure,” for seven years beginning in 1963, after being framed in the early 1960s for robbing a London bank van.

In 1978, Keith Moon died at age 32 as a result of swallowing too many pills designed, sadly enough, to reduce his alcoholism. Townshend would invite the drummer of the Faces, Kenney Jones, to join The Who. Daltrey writes, “We signed him in for a quarter share of the band, which was just stupid. Pete wanted it that way so Pete had it that way and I gave in for the quiet life,” adding that he never liked Jones’ drumming:

I got on with him better than the rest of the band. He was also a great drummer. But he was completely the wrong drummer for us. He was right for the Faces. That’s not meant to sound disparaging. At the time, people thought I was saying Kenney was a crap drummer. I have never ever said Kenney was a crap drummer. He was a crap drummer for The Who, just as Keith would have been for the Faces. He was wrong, very wrong, for us.

Who’s Last

Unlike Led Zeppelin, who called it quits in late 1980, when their drummer met his own alcohol-related demise, The Who took the opportunity of Moon’s untimely death to hit the road, release the movie version of their album Quadrophenia, and record with Jones. By 1981, Townshend, via a combination of the stress of having to write songs to meet the lucrative record deals The Who and he as a solo artist had signed, the tragedy of the 11 killed at their 1979 Cincinnati rock concert, and other strains, had become addicted to cocaine, heroin, and alcohol. Eventually, after nearly dying of a heroin overdose, he checked himself into a rehab clinic led by Dr. Meg Patterson, the Scottish surgeon who had previously helped Eric Clapton and Keith Richards detox.

According to Daltrey, all of this turmoil led to his decision to declare the band’s 1982-1983 tour their last ever:

It all crystallized for me in September 1982. I was on my way to do the launch of the record’s accompanying tour. Another forty-two shows. Another three-month haul across North America. I was doing the launch on my own, as usual. Pete wanted nothing to do with promotion. He didn’t want to do interviews or photo shoots. Nothing. So I was on my own in the car, trying to build up the enthusiasm, and I just made the decision. That was it. This would be our last tour. I made the announcement at the press launch and I knew it was the right decision. It solved all our problems. Pete would have no more pressure on him. The drummer problem wouldn’t exist anymore. It took the band completely by surprise, but I knew that if we had just carried on it might have killed him.

The ostensible last concert by The Who was performed in Toronto on December 17th, 1982. I’ve seen it many times on laser disc (I attended their September 25th, 1982, show at Philadelphia’s cavernous old JFK Stadium). It’s a desultory affair, with the band occasionally catching fire, but largely going through the motions. Despite everyone in the band believing that this was their last gig, no guitars were destroyed by Townshend, despite his playing kit-built replicas of Fender Telecasters that the band purchased in bulk and could easily be salvaged. In Thanks a Lot Mr. Kibblewhite, Daltrey doesn’t discuss what was it was like to go from being in (apologies to Paul Shaffer) the world’s most dangerous band, to a group phoning it in on their last live concert.

Of course, after one-off appearances with Jones at Live Aid in 1985 and a performance in 1988 when the band received the British Phonographic Industry’s Lifetime Achievement Award, The Who would eventually reform in 1989, with the promise of lucrative tours of America’s sports arenas. As Daltrey writes, “With no work since 1982, John Entwistle started to run out of money by the end of the eighties. For that matter, so did I. It’s expensive living the life of a rock star when you’re not earning rock star money.”

The Song Is Over

But while Daltrey writes that “we had been through a traumatic few years, but our music was still there … smoldering” (ellipses in original), he never discusses how, with the exception of their one-off album Endless Wire album in 2006, Pete Townshend, one of the greatest songwriters of the 1960s through the early 1990s, had largely stopped writing music — at least new music that was being released commercially. From 1964 through 1982’s It’s Hard, every year or two or three, audiences were regularly graced by new songs written by Townshend and performed by Daltrey and The Who. This virtually stopped when The Who reformed in 1989. Unfortunately, Daltrey never discusses what he thought about Townshend’s diminished output as a commercial songwriter, if only to blame the dearth of new material on the changing economics of the post-Napster record industry.

However, Daltrey does go into extensive details of the lowest point of Townshend’s later career: his 2003 arrest for attempting to download child pornography, in an effort to prove, Daltrey writes, “that the credit card companies were taking money from child pornographers.” As Daltrey eventually concludes:

Pete had to wait a long time to find his way out of his darkness. In May 2003, the charge that he’d downloaded photographs was dropped. They hadn’t found a single picture. He hadn’t been on the website. He hadn’t viewed any images. I’m sure if he had they would have done him. As he put it years later, when he finally felt able to talk to the press about it, “A forensic investigator found that I hadn’t entered the website, but nonetheless, by the time the charges came to be presented to me, I was exhausted.” He had admitted that he’d provided his credit card details right from the start, and that was enough to break the law, so he took that part of it on the chin.

And in the end we did what we always did. We got back onstage.

Which has been The Who’s existence since 1989. Whatever complaints I have about what’s missing from Daltrey’s autobiography, they’re all minor grouses. If you’re as obsessed with The Who as I am, Thanks a Lot Mr. Kibblewhite is a must-read, and a quite enjoyable one at that.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member