With Gibson issuing a new Pete Townshend-branded Les Paul guitar, the music manufacturer’s Website reprints a 2002 interview with Townshend discussing Scoop, his first of three albums (and Scooped, a best-of anthology) collecting the home demo recordings of the songs he would give to The Who to record in a proper studio environment. Because neither Townshend nor his fellow band members read music notation, working in his home studio, Townshend typically recorded guitar or piano, then added rudimentary bass and drum parts for John Entwistle and Keith Moon to build upon, and a guide vocal for Roger Daltrey to follow. At 7:10 into this BBC South Bank Show from the mid-’80s, Townshend illustrates the mechanics of the process, using Elvis’s “That’s All Right, Mama” as an example:

On some songs, such as “Won’t Get Fooled Again,” the band restructured Townshend’s parts and built a song far more powerful than his original demo. But as Townshend’s demos got more and more complex and professional sounding, many of their songs, such as “Who Are You” stayed remarkably true to his original recording. Townshend also recorded lots of material that he knew would never be used by The Who as musical experimentation, therapy, and to test out new equipment and recording concepts.

Most of the material on the Scoop albums is multi-instrumental and fully arranged. Did you always try to completely arrange the songs before taking them to The Who?

Yes. The reason for doing this is that The Who is a simple rock band with an extremely parochial style and sound. To influence it one must be very specific about what one wants. So a full orchestral piece recorded by The Who will sound orchestral, but there will be no orchestra. The other reason for trying to deliver complete demos is because up until now—and this may well change—I have always wanted to be the composer up until the recording starts, and from then on the guitar player. I have never felt comfortable tearing my own stuff apart with the band during recording. So I become a little detached. I find myself behaving like a session man. I do my job. I play guitar with The Who much as I do on stage these days. If the demo is complete, even I am able to react to it with more detachment and objectivity than if there were deliberate “spaces” for creative and interpretative input.

* * * * * * * *

Did you consciously strive to write toward the strengths of the individual members of the band?

Always. On “My Generation,” I made the demo with a six-string bass and played a solo because I knew that would suit John. I put in a stutter because Roger and I were both huge fans of both John Lee Hooker and Johnny Cash, and both [of them] occasionally stuttered. When I started to employ drums on my demos I tried not to overplay, but I certainly would have played like Keith sometimes if I could. After I heard [The Band’s] Music from Big Pink, I wanted my demos to sound tight and cool. That’s why the demos for Who’s Next are so good, because I tried very hard indeed to emulate the sound of The Band to some degree.

* * * * * * * *

You’ve always seemed to have an especially intense love of the studio—much like Prince, it seems to me. Does the studio inspire you as a writer?

Yes. I love Prince and the way he uses the studio as his template for whatever is happening in his life. For people like us, the studio is like a golf-course! It’s strange to think that one can be inspired by technology, but one can. For example, “Drowned” [from Quadrophenia] was written purely to test my first one-inch 8-track machine. It is a fantastic song, but I just knocked something out so that I could play. Music is something you play at. It’s play—like golf, sailing, model trains, engine restoration, etc. It’s quite a man thing, I think.

As Brian Eno’s old line goes, “the first Velvet Underground record sold only 30,000 copies in its first five years. Yet, that was an enormously important record for so many people. I think everyone who bought one of those 30,000 copies started a band!”

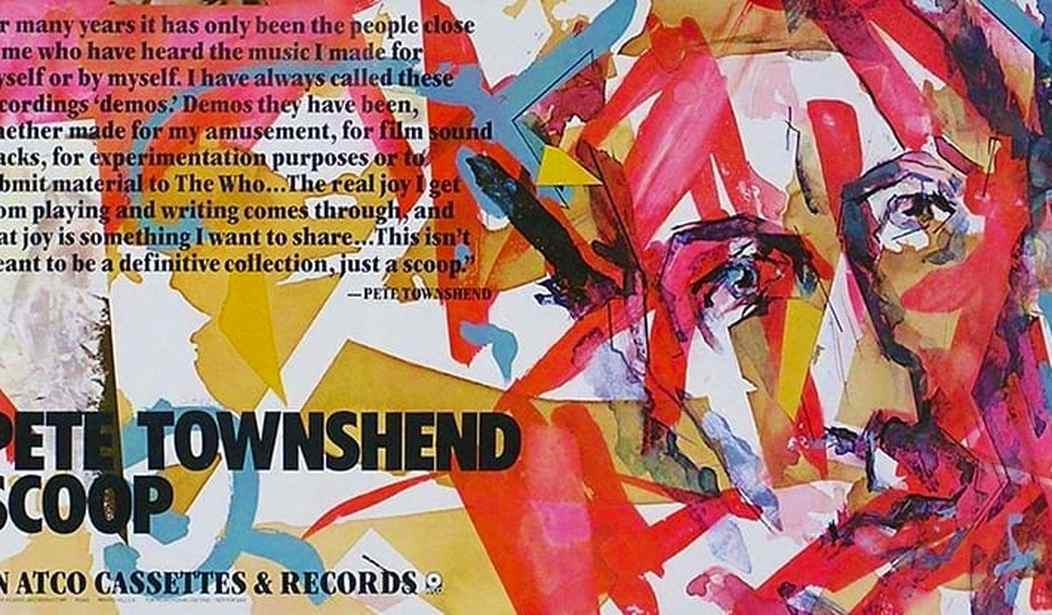

That was true for me as well — I bought my copy shortly before co-founding my college-era rock band, but Scoop made an infinitely more profound impression on me. (More on that in a moment.) Scoop was released in 1983, right around the time the first cassette four-track recorders were appearing in music stores. And according to Townshend, he played a role in developing them during the previous decade:

Yes. I am pleased to have helped develop and demand equipment for this purpose. There are others, like Joe Meek, Wendy Carlos, Les Paul, and Eddie Cochran and so on—who worked in complex home studios long before I did. But I helped develop the first portastudio. It was me and a fellow called Andy Berraza who, in 1971, came up with the idea to use a four-track car cassette head block (designed to play two tracks but in two directions) as a one-direction 4-track. Andy somehow managed to solve the problems of the delicate bias issues, and sold it to Fostex. Prior to that I had invented the Junior Songwriter’s Kit for [Faces’ guitarist and one-time Townshend collaborator] Ronnie Lane—two Dolby Cassette machines in an attache case for overdubbing. I have always encouraged songwriters to have their own studios. Composers should be like painters. If you can’t write notation, you must have a scratch pad you can use at any time night or day—almost in any place too. These days, all this is possible.

It definitely is possible with computers and even iPads equipped with the right software and interface, but in the early ‘80s, home multitrack recording was pretty radical stuff. At least for me – I was on a path to managing (and eventually owning) my parents’ retail store in southern New Jersey, but learning how to play guitar, and then writing my own songs on four-track, initially using guitar, drum machine, an electric bass, and eventually synthesizers freed up all sorts of creative impulses. During college, I figured that if I could write songs, I could write articles and create videos.

I didn’t know it, but in the mid to late-‘80s, I was acquiring many of the skills I would need 15 years later for the early days of blogging. And it’s no coincidence that several of us who pioneered blogging had one leg in journalism and the other in DIY music. Today, the Photoshops I do for PJM also have a sense of multitrack recording, insomuch as with a 24-track recorder, they’re built on layers and layers of treated and manipulated images. Quincy Jones once described multitrack recording as feeling akin to “Painting a 747 with a Q-Tip,” and some of the more involved Photoshops I’ve done have felt very much like that as well, at times. And there’s no way I would have begun doing this without all of the other prior DIY experiences, which is why a framed print of the above 1983 record store ad for Scoop is on my office wall.

I apologize if this sounds like an out-of-control ego bragging. I’m very well aware of the limitations of my skills in all of the disparate fields in which I work. But I’m also a big fan of something that Julia Cameron wrote in her best-selling how-to guide for the budding or recovering artist, The Artist’s Way:

Judging your early artistic efforts is artist abuse…In recovering from our creative blocks, it is necessary to go gently and slowly. What we are after here is the healing of old wounds — not the creation of new ones. No high jumping, please! Mistakes are necessary! Stumbles are normal. These are baby steps. Progress, not perfection, is what we should be asking of ourselves. Too far, too fast, and we can undo ourselves. Creative recovery is like marathon training. We want to log ten slow miles for every one fast mile. This can go against the ego’s grain. We want to be great — immediately great — but that is not how recovery works. It is an awkward, tentative, even embarrassing process. There will be many times when we won’t look good — to ourselves or anyone else. We need to stop demanding that we do. It is impossible to get better and look good at the same time.

* * * * * * * *

in order to recover as an artist, you must be willing to be a bad artist. Give yourself permission to be a beginner. By being willing to be a bad artist, you have a chance to be an artist, and perhaps, over time, a very good one.

As with most veteran rock stars earning a living on the stadium/casino circuit in an era where the Internet has effectively destroyed the notion of the record album, Townshend seems resigned to mostly touring off his back catalog, rather than releasing much new material. But there was a time, from his first solo album through the mid-‘80s (culminating in his brilliant 1985 charity concerts in Brixton) where he was making highly innovative, highly listenable music.

And providing more than a scoop of inspiration for others who wished to be creative as well.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member