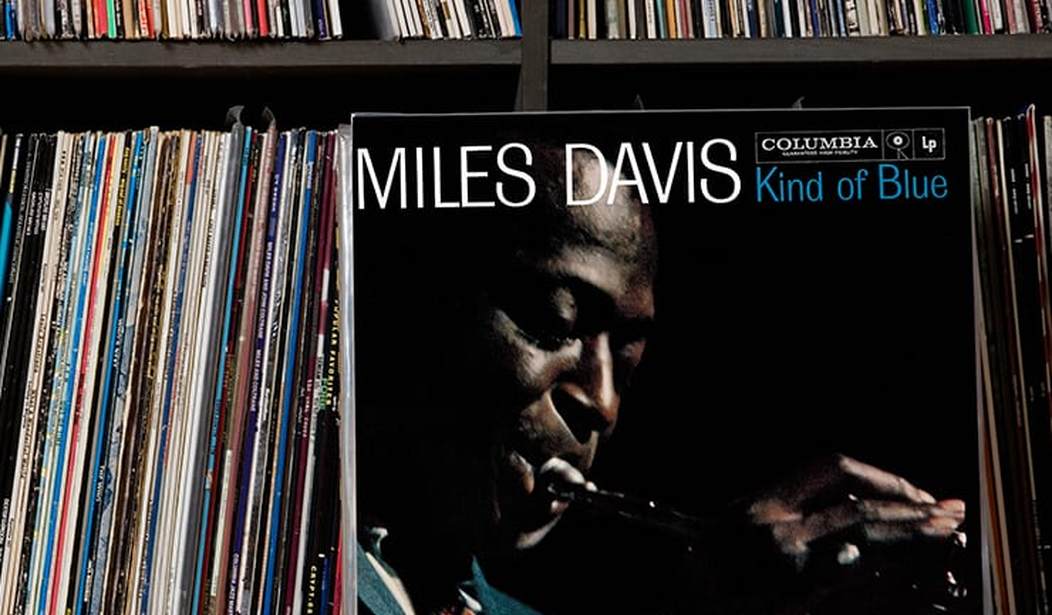

In an article published on Sunday, the British edition of GQ listed Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue as the number one title on its list of “The 100 best jazz albums you need in your collection,” and noted:

Miles’ soft, muted trumpet sound (dry as a martini) has become synonymous with “cool” jazz, and there is no better example of the genre, or of his art, than this album. Kind Of Blue is the best-selling recording in his catalogue and the best-selling classic jazz album ever. It regularly tops All Time Favourite lists, and had become a template for what a jazz record is meant to be. It is also perhaps the most influential jazz record ever released. Musically, it’s where modal jazz really hit paydirt, and where linear improvisation came to the fore (Davis playing Samuel Beckett to John Coltrane’s James Joyce), and its tunes have been covered by everyone from Larry Carlton to Ronny Jordan. Influence is far-reaching; “Breathe” from Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of The Moon was based on a chord sequence from this album. From its vapoury piano-and-bass introduction to the full-flight sophistication of “Flamenco Sketches”, Kind Of Blue is the very personification of modern cool. And, according to Steely Dan’s Donald Fagen, it is also something else far more important: “Sexual wallpaper”.

Heh, indeed, as Glenn Reynolds would say over at PJ Media’s sister website, Instapundit. Earlier this month, the online music retailer Sweetwater looked back at Kind of Blue on its 60th anniversary, and explored how that “modal jazz hit paydirt” in detail:

In 2002, during the very early days of the now moribund Blogcritics website, I reviewed music historian Ashley Kahn’s then-recent book, Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece. Since that article is no longer online, here’s a lightly-edited reprise:

Very, very few artists can be said to have changed the course of their medium even once. Miles Davis (1926-1991) changed the direction of jazz three times.

First with 1949’s The Birth of the Cool, Davis, early in his career as a bandleader, slowed the frantic tempo of bebop down, and introduced the world to cool jazz. This would be the dominant form of jazz, especially as played by west coast musicians, for the next decade.

In 1969, Davis released Bitches Brew, a double album of what would eventually be described as jazz-rock fusion. Fusion, of course, would be the dominant form of jazz (for better or worse) for the next decade, and the players on Bitches Brew (which include John McLaughlin, Joe Zawinul, Wayne Shorter, and Chick Corea) would be its chief proponents.

In between those two extremes, in 1959, Davis introduced modal jazz to the world. Modes are scales of musical notes, some of which date back thousands of years. The appeal of modes for jazz musicians was to get away from playing constant chord changes, which were felt to hamstring the soloist, and provide a sparse, less cluttered background for solos, providing maximum flexibility and expressiveness. In the hands of an amateur, who needs the chord changes to influence his selection of notes when soloing, the result is cliched scale after scale (this would become the curse of the jazz/rock fusion genre). But in the hands of master musicians such as Davis and his bands, the results were obvious: a new composition style instead of relying of old standards, a greater freedom of expression, and a unique new sound that would be jazz’s dominant form for the next 30 years, and remains one of its most important elements. The album that introduced this sea change was, of course, 1960’s Kind of Blue.

Along with John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme and Giant Steps, Kind of Blue is one of those albums that even non-jazz fans own — they are definitive recordings from the 1960s. And yet, no album emerges in a vacuum. There’s rarely a moment of divine inspiration behind an artwork — it’s almost always a combination of talent and hard work, combined with an enormous amount of thought.

Kind of Blue is no exception. It was a logical progression in Davis’ career, and in his ability to choose excellent sidemen. Davis had the core of a crack band at the time of Kind of Blue’s two 1959 recording sessions, with Jimmy Cobb on drums, Paul Chambers on bass, and the dueling saxes of the avant-garde John Coltrane (soon to leave for a solo career that would rival Davis’ in its stature and influence) and the more conventional, but playful technique of Cannonball Adderly.

Davis toured with pianist Wynton Kelly, who plays on Kind of Blue’s bluesy “Freddie Freeloader,” but a few months prior to the recording session Davis recruited Bill Evans, who was quietly earning a reputation as the pianist in jazz, with the chops to handle any material, and an innovator in his own right.

This was the group that walked in Columbia Record’ 30th Street studios in Manhattan to record Kind of Blue. Ashley Kahn, in Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece covers this session, the events leading up to it, such as Davis’ then rapidly rising stature, his 1955 signing to Columbia, which provided the budgets and studios to allow Davis to produce “concept albums,” often with a small orchestra behind him, a decade before the Beatles made both concepts popular in rock music.

Kind of Blue would not exist in its current form but for Davis’ astute hiring of Bill Evans. Kahn sketches Evans’ career up to Kind of Blue, and briefly, but effectively covers the “Crow Jim” reverse racism that Evans occasionally received from black audiences when performing as the only white member of an otherwise black group.

(He also mentions the hilarious request of Davis before he allowed Evans into the band: “You got to make it with everybody, you know what I mean? You got to f**k the band.” The straitlaced Evans stuttered in reply, “I’d like to please everyone…but I just can’t do that”. Davis’s sardonic humor, and attempts to mess with the minds of his musicians would eventually become the stuff of legend among his band members.)

All of these anecdotes demonstrate Kahn’s most important writing skill: the ability to describe, (in fairly short, and splendidly illustrated chapters) the history of the recording sessions, Davis’s career, his meteoric rise prior to Kind of Blue, and that album’s impact on the jazz world as a whole, both in the 1960s, and today, as it sold an astonishing 5000 copies a week 40 years after its release.

Kahn’s effortless style belays the intense research and reporting that makes it possible. To describe the actual recording session, Kahn uses a remarkable collection of skills that combine his simultaneous role as historian, detective, and musicologist. He assembles material gleaned from existing interviews with Davis and his band members and the album’s producer, Irving Townsend, new interviews with Jimmy Cobb, the last surviving member of that session, photographs of the session (ironically, Cobb was never clearly photographed, since he spent most of the session behind his kit), and numerous quotes transcribed from the band’s own comments recorded onto the studio session tapes. His best detective work is determining, with a fairly high degree of certitude, that Gil Evans (no relation to Bill Evans) wrote the introduction to the first track of the album, “So What,” perhaps the most beautiful 30 seconds or so in all of jazz.

Kahn also describes the careers of Davis and his band members immediately after Kind of Blue, including Davis’ epochal 1961 concert at Carnegie Hall, with his five-piece band, and the Gil Evans Orchestra backing him on one of the greatest live recordings in all of jazz.

Kind of Blue is an album that simultaneously evokes an era, while remaining timeless. Ashley Kahn does a masterful job of both explaining that era, and why Davis’ music from it remains astonishingly popular today.

2019 Update: Enjoy Miles’ best music (before he became entranced with jazz/rock fusion and ’80s pop) while you can. It’s only a matter of time before he’s memory-holed by #metoo, as this 2013 article in the Onion’s A/V Club section portends: “Miles Davis beat his wives and made beautiful music.”

Join the conversation as a VIP Member