A week after riots ripped through Charlotte, N.C., Hillary Clinton visited an African-American church this past Sunday morning in the Queen City, and instead of bringing solutions to the real problems plaguing the black community, she capitalized on black people’s fears to secure their votes.

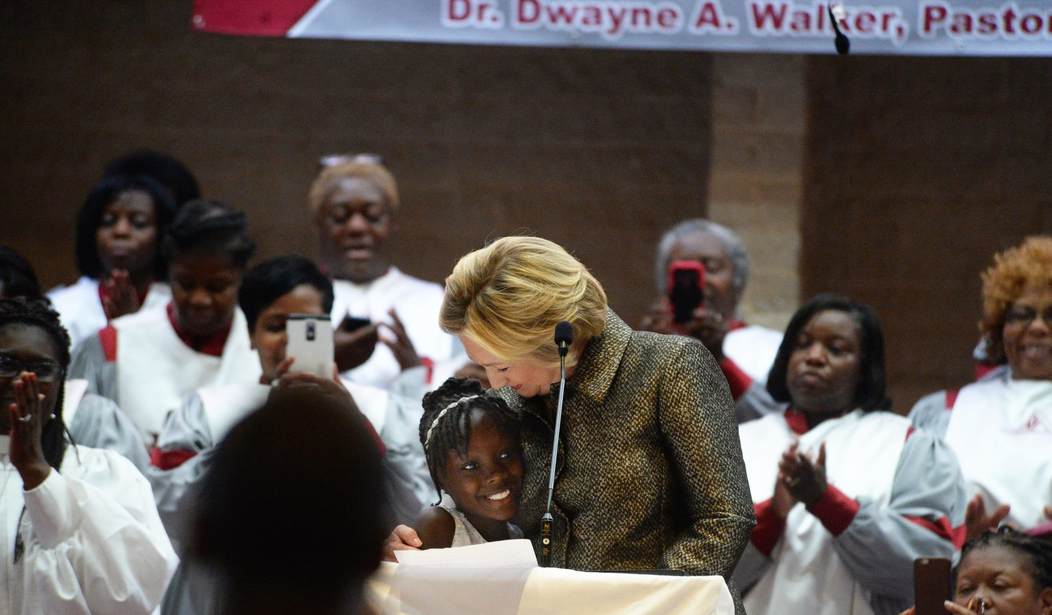

This was Clinton’s first visit to Charlotte since protests and riots broke out in response to the shooting death of an allegedly armed black man with a violent criminal record. She attended a worship service at Little Rock AME Zion, which is the same church where the NAACP held a presser in response to the death of Keith Lamont Scott by a local police officer, who was also black.

“Our entire country should take a moment to really look at what’s going on here and across America,” Clinton told the congregation. “I believe we need end-to-end reform in our criminal justice system.”

While Clinton called for people not to “let hate infect their hearts” and encouraged her listeners to appreciate police officers, she maintained that the fears and concerns of the black community over racial discrimination in our justice system are warranted, and she repeated calls for gun control.

Clinton also referenced a 9-year-old girl who had spoken before the Charlotte City Council last week and called her “courageous.”

“I don’t like how we’re treated just because of our color,” 9-year-old Zianna Oliphant declared last week in a city council meeting. “We are black people, and we shouldn’t have to feel like this. We shouldn’t have to protest because you all are treating us wrong. We do this because we need to and have rights.”

Is what’s “really going on here” racial discrimination, as Clinton and this young girl claim? Are the tensions in Charlotte rooted in institutionalized racism, or is it something else? If it’s something else, will Clinton’s call for criminal justice reform and gun control actually help the black community?

No, it won’t. It won’t because problems in the black community are not due to racial discrimination or institutionalized racism within our judicial system or any other system for that matter. To put the blame on racism (in other words, to blame white people) for the trials and tribulations of the black community is to purposely turn a blind eye to the real problems they face and leave them unsolved.

And what are those real problems? Let’s take a look at Charlotte in particular. Earlier this year, many months before the city erupted in violence, city leaders discussed the growing trend of racial unrest throughout the country and its impact on Charlotte. They also addressed a dramatic increase in homicides in the Queen City.

Even though blacks make up only 35 percent of the Charlotte population, most homicide victims are black (28 out of 43). Most of those are black men, and a majority of those are under 30. A total of 63 percent of homicide victims and 68 percent of homicide suspects are black men. In other words, most of the violent crime in Charlotte is black-on-black crime.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Chief Kerr Putney, who has been in the national news lately because of the Scott shooting, expressed concern months before about problems in the black community and wanting to find solutions. He told the city council in January that he wants to keep up with rising crime.

As reported in the Charlotte Observer, Putney said he needed more personnel. “In order to have the ability to be flexible and have those innovative strategies, you also need the resources.” But what’s most important, he said, is getting to the root causes of crime — economic and social dysfunction.

Of all the homicides in Charlotte, nearly half are caused by toxic relationships. Domestic violence is a huge source of strife in the black community, and it’s not something criminal justice reform will fix.

“If you’re in a toxic, violent relationship until you break that cycle, we’re kind of defenseless to assist in preventing some of these,” Putney said.

As Cleve Wootson of the Charlotte Observer reported earlier this year, there are many factors at play when looking for solutions to the troubles of Charlotte’s black community. Domestic violence is certainly one of them, but another is “antipathy toward police departments.”

This is “increasing in the wake of highly publicized shootings of unarmed individuals, particularly minorities. The tension makes people less willing to cooperate with police to solve crimes, keeping violent criminals on the streets,” criminologists told Wootson.

Kami Chavis Simmons, the head of Wake Forest’s criminology department, said recent high-profile police shootings of minorities may be intensifying the disparity. Crime victims and witnesses in minority neighborhoods may be less willing to cooperate with officers, leaving violent criminals on the street for longer, and increasing the chance that they’ll commit more crimes.

“If you can’t trust the police officers, it is very difficult to form partnerships and for people to want to cooperate with them,” she said.

The more blacks believe the narrative that the system is rigged against them, the less likely they will cooperate with police and the more likely they will interpret disparity in arrests and crime rates with racial injustice.

This disparity, however, is more about socioeconomics than race.

“What we are experiencing is a culture of violence in low-income communities where they are socially and economically isolated without the type of mentorship or visible signs of hope,” Patrick Graham, the president and CEO of the Urban League of Central Carolinas, told Wootson. “It’s the notion that you can’t rise above the circumstances in which you live. And a lot of times it’s very hard to envision something when you don’t actually see any examples of it.”

Family breakdown, gangs, school drop-out rates—all the same problems that plague other communities across the nation can also be found in Charlotte. But, again, the solution is not criminal justice reform and gun control, as Clinton says. It’s getting into these communities, setting up mentoring programs, rebuilding families, and creating real economic opportunities to combat isolation and despair, not increasing government handouts or putting the blame on a fictional “racist” system.

Police and government officials can create some initiatives to try to make a difference, but when it comes to the fundamental problems, change has to come from within the black community itself. Instead of clinging to the promises of the Democratic Party to reform institutions they say are racist and oppressive, blacks should partner with police to reduce violent crime and empower themselves to bring about real reform in their own lives and in their own communities.

The solution doesn’t lie in the promises of liberals like Clinton. That’s because liberalism is part of the problem.

This is a point made by former NFL football star Burgess Owens, who recently wrote Liberalism or How to Turn Good Men into Whiners, Weenies and Wimps.

“We live in the greatest country in the history of mankind every single day,” Owens told Glenn Beck recently. “We do not have a racial crisis, we have an ideology crisis. We have socialists, Marxists and liberals who have hijacked my race.”

From 1865 to 1965, my race, the black race, was one of the most competitive, entrepreneurial, Christian, moral races in our country. We had the highest percentage of entrepreneurs in the country, the highest percentage of marriage in the country. And we were so competitive, black entrepreneurs, that in 1932, the Democrats had put together a law called the Davis-Bacon Act to help protect the white unions against us.

Where we are today is 80 percent of black females are unemployed across this country. Seventy-six percent of black men abandon their children, forsake marriage. We have illiteracy running afoul. There’s more black males dropping out of high school than dropping out of college. This is the end result of liberalism, and it’s not an accident.

Burgess’s message to the black community is the opposite of that given by liberal politicians like Hillary Clinton. As he told Alex Marlow of Breitbart News Daily, “White Americans, stop apologizing.”

If you apologize to me, I look at it as an insult because my parents, my grandparents, my great-grandparents, like every other culture out there, did exactly what they needed to do. They worked hard, and they became part of the American way, and they earned the respect of Americans across the board. We need to do the same. We need to step up because our past generations did their jobs; we now need to do ours.

This is the message the black community needs to hear, not just in Charlotte, but across the country. It’s a message of freedom and personal responsibility. It’s a message of hope.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member