This past week, Texas State Historical Association chief historian Walter Buenger made two controversial assertions regarding the Alamo in a story published by USA Today.

Although the battle has become a symbol of patriotism and freedom for many Texans and Americans, like the Confederate monuments erected after the Civil War, the myth of the Alamo has been used to “commemorate whiteness,” according to Walter L Buenger, Texas State Historical Association chair.

The battle itself was relatively insignificant tactically speaking, but it gained recognition decades later in the 1890s as backlash to African Americans gaining more political power and Mexican immigration increasing, Buenger said. In 1915, “Birth of a Nation” director D.W. Griffith produced “Martyrs of the Alamo,” which solidified the myth further by pitting white virtuous Texans against racist caricatures of Mexicans on screen.

“It became in some ways a sort of symbol of Anglo-Saxon preeminence,” he said. “The Alamo became this symbol of what it meant to be white.”

Buenger is currently the Texas State Historical Association’s chief historian as well as holding a major post at the University of Texas at Austin. The TSHA is not a state agency, it’s a nonprofit, but it plays a key role in history education in Texas schools, and of being an authoritative repository of the state’s history through its online Handbook of Texas. As Michelle Haas, editor of the Copano Bay Press, notes, Buenger’s role lends him a great deal of influence and power over how Texas history is recorded and taught.

In the article, Buenger asserts that the Battle of the Alamo was “tactically insignificant” and that it wasn’t recognized as important until decades after the battle, and then only as a “backlash to African Americans gaining more political power.” Both of these assertions, if true, undermine the common understanding of the Alamo battle as one of, if not the most important, turning points in Texas history and suggests Texas is and always was racist.

Are Buenger’s Claims True?

The Alamo had nothing to do with the Confederacy or the Civil War, which occurred 25 years after the famous Texas battle. None of its defenders can be held responsible for its misuse by anyone, including 20th century filmmakers or 21st century historians. Buenger’s attempt to connect the Alamo to misuses long after the battle is misguided at best, and unfair. But what about his factual claims: that it was strategically unimportant at the time, and that it was only recognized as important in the context of a racial backlash?

Let’s take the first claim, that the battle itself was “tactically insignificant.” I reached out to Texas historian Dr. Stephen Hardin. Hardin is professor of history at McMurray University and is widely regarded as one of the preeminent Texas historians. He has authored numerous books on Texas history including Texian Iliad, which chronicles the Texas Revolution. Hardin wrote the TSHA’s Handbook of Texas entry about the Battle of the Alamo.

Hardin referred me to an article he wrote, titled “Lines in the Sand, Lines on the Soul: Myths, Fallacies, and Canards That Obscure the Battle of the Alamo.” In that article, which first appeared Texan Identities: Moving Beyond Myth, Memory and Fallacy in Texas History (2016, University of North Texas Press), Hardin tackles the assertion that the Battle of the Alamo was not significant in military terms. Hardin calls this claim a “myth.”

Strategic Value

Hardin notes that the Alamo sat on one of the two roads into Texas from Mexico. One of these was the Atascosito Road, which led to the south toward Goliad and Presidio La Bahia, which had been converted into a revolutionary fortress and renamed Fort Defiance. About 400 revolutionaries under the command of Col. James Fannin occupied that fort. The other road was the El Camino Real, or the King’s Highway, which led toward the north and San Antonio, which was the capital of Texas at the time. Both of these facts lent the Alamo strategic importance in 1836. Whoever controlled the Alamo could more easily control the capital city and the key road into Texas. Additionally, Texian and Tejano forces had captured the Alamo from Mexican forces in late 1835, which lent it symbolic and strategic importance for both sides.

Dictator Santa Anna apparently viewed the Alamo as important. At the beginning of 1836, he faced rebellion not just in Texas but also in several other provinces concurrently. The rebellion had nothing to do with “whiteness,” which is a politically-charged 21st century term. Santa Anna had done away with local power and declared himself a Centralist — and dictator. He had done away with the 1824 Constitution, which granted great power to the provinces in a federalist system (Texas was part of the combined Texas y Coahuila province at the time, with San Antonio as its capital). In the 1835 Tormel Declaration he had declared that Anglos who sided with the Federalists would be given no quarter. He had declared his intent to drive all Anglos out of Texas — which we might call ethnic cleansing today. Santa Anna also faced the defection of officials including diplomat and physician Lorenzo de Zavala, a Federalist, after he declared himself a Centralist.

De Zavala would later serve as Texas’ first vice president. If “whiteness” lay at the heart of the revolution, de Zavala would never have been elected to any office. “Whiteness” would also fail to explain why the Esparza brothers, Damacio Jimenez (sometimes spelled Ximenez), Carlos Espalier, and other Tejanos fought and died at the Alamo, and why Jose Torbio Losoya was possibly the last defender alive. His body was recovered just inside the doorway at the Alamo church. Was he fighting for “whiteness” in an “insignificant” military engagement? Losoya wasn’t white, and he was a professional soldier who began his service in the Mexican army. Why did he join the revolution and defend the Alamo to the end?

Another fact runs against the “whiteness” theory. A slightly greater percentage of Tejanos than Anglos fought for Texas’ independence from Mexico, according to Dr. Jody Edward Ginn. Ginn wrote the 2014 Standing Their Ground: Tejanos at the Alamo exhibit at the Alamo. An expert in Texas history and executive director of the Texas Rangers Heritage Center, Ginn studied under Frank de la Teja, Texas’ premier Tejano history expert. Ginn also served as a consultant on Netflix’s The Highwaymen and is the author of the great East Texas Troubles: The Allred Rangers Cleanup of San Augustine.

Santa Anna’s Objectives

The argument over governance, contested by Federalists on one side and Centralists on the other, and Santa Anna’s related abrogation of the 1824 Constitution, was the primary cause of the Texas Revolution. Federalists sought a system similar to that of the United States. Centralists sought a much stronger central national government with little power afforded the provinces. Race was a factor in the war, but not likely in the way Buenger probably sees it: Santa Anna sought to drive all “perfidious foreigners” — American and European Anglos — out of Texas. As noted above, such designs in the 21st century might be viewed as ethnic cleansing.

When he marched into Texas, Santa Anna sought to crush the rebellion swiftly. He divided his forces into two divisions, one to march north to recapture the Alamo and the other to move south and attack Fannin’s forces at Goliad. Santa Anna placed the Goliad column under the command of the highly competent Gen. Jose de Urrea. Santa Anna himself led the force to attack the Alamo, which would suggest to anyone who knows their military history and Santa Anna’s character that he regarded this effort as the most important. Facing widespread rebellion and defections and with the choice of which column to lead in his hands, Santa Anna personally prioritized capturing the Alamo. Was the “Napoleon of the West” mistaken in his military priorities?

Adding to its symbolic and strategic importance due to its geography is the fact that some of the most famous and feared Texas revolutionaries were present at the Alamo: David Crockett, James Bowie, William Barret Travis, and Juan Seguin. Tejano leader Seguin was present leading the Tejano defenders when the siege began. He rode out through enemy lines, on Bowie’s horse, during the siege with a call for reinforcements. Colonists from Gonzales, numbering about 32, were the only ones to answer Travis’ call through Seguin. Santa Anna’s tactical objectives at the Alamo were to recapture the fortress and the capital city, control the road, and eliminate some of his most dangerous foes at once. The Alamo alone offered this opportunity.

The Alamo Battle and the Texas Revolution

When he encircled the Alamo, Santa Anna might have been wise to follow Sun Tzu’s advice to leave a surrounded enemy a path to retreat. Had he done so, their retreat may have let much of the air out of the resistance. It certainly would not have created 189 immortal martyrs.

Santa Anna left no such path. He intended to intimidate the revolutionaries into submission by crushing the garrison, sparing no quarter, and burning the bodies of the defenders on pyres alongside the road into and out of San Antonio. His actions instead enraged and galvanized the revolutionaries. They knew from that point forward they must fight for their very lives or Santa Anna would hunt them down, kill them, and deny them even a proper burial. He proved his intentions at the Alamo and Goliad.

The strategic importance of the fall of the fortress on March 6, 1836 was immediately understood. Santa Anna controlled the capital and the El Camino Real. He could move virtually unopposed. Once Urrea took the Goliad forces out, Santa Anna could then combine his forces to pursue and destroy the final Texian force, commanded by Sam Houston. Texian and Tejano families, fearing the worst, began to flee to the south and east in the Runaway Scrape.

Newspapers reported the fall within days to weeks, and as Hardin notes in his article, word spread beyond Texas quickly. U.S. President Andrew Jackson reacted in a letter to his nephew on April 22, 1836. He told his young nephew that his reaction to the “death of those brave men who fell in defense of the Alamo displays a proper feeling of patriotism and sympathy for the gallant defenders of the rights of freemen.” News had spread far and wide within weeks, all the way to the White House.

One day prior to the date of Jackson’s letter, the Texians and Tejanos defeated Santa Anna at San Jacinto, shouting “Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!” as they surprised and routed the dictator’s forces. Seguin was there, leading the Tejanos providing rearguard security for the Texians under Sam Houston.

The San Jacinto battle cry leads to another key point: context. Warfare includes both strategic and propaganda or symbolic importance. The fall of the Alamo, and Santa Anna’s brutal treatment of the fallen, affected the thinking and the morale of both sides. It all happened in context: Santa Anna’s betrayal of the Federalist colonists when he switched to the Centralist side; the Tornel Decree which offered no quarter for Anglos supporting the Federalists; the former American colonists’ role as children and grandchildren of the American Revolution; Santa Anna’s ambition and his abrogation of the 1824 federalist Constitution; and many Tejano Federalists’ choice to side with the Anglos against Santa Anna.

For many Mexican soldiers and officers, Santa Anna’s conduct caused them to question and later repudiate him. His brutality at the Alamo and his order to massacre about 400 captured revolutionaries at Goliad and burn their bodies horrified many of his officers and conscripts alike. He had ordered his own soldiers to commit what today would be considered war crimes in the context of an ethnic cleansing campaign. Mexico’s officers were moral Catholics. Gen. Vicente Filisola, an Italian who was Santa Anna’s overall second in command at the time, denounced Santa Anna’s brutal actions at the Alamo in his 1848 memoir as “atrocious authorized acts unworthy of the valor of and resolve with which the operation was carried out.” Filisola added that Santa Anna’s actions helped ignite the rebellion (Sea of Mud: The Retreat of the Mexican Army after San Jacinto, An Archeological Investigation, Dr. Gregg Dimmick).

Filisola was attempting to rehabilitate his own reputation but he was right about the effect of Santa Anna’s actions; they backfired and ignited rebellion. Santa Anna’s actions removed any possibility of reconciliation with the revolutionaries — Anglo or Tejano.

Newspaper reports of the time capture the battle’s importance. On March 24, 1836, The Telegraph and Texas Register of San Felipe de Austin declared “Spirits of the mighty, though fallen! Honors and rest are with ye: the spark of immortality which animated your forms, shall brighten into a flame, and Texas, the whole world, shall hail ye like the demi-gods of old, as founders of new actions and as patterns of imitation!” Less than three weeks after its fall, the Alamo was already seen as lending its fallen defenders “immortality.” Some might call that wartime propaganda. That’s right, which only reinforces the view that the Alamo was important at the time, not just decades later. This report became the template other newspapers used to report the battle, according to the Daughters of the Republic of Texas.

Writing in the Southwestern Historical Quarterly in 1988, the late Michael P. Costletoe, professor of Hispanic and Latin American studies at the University of Bristol (England), noted that Mexican newspapers including the country’s official newspaper reported the Alamo’s fall jubilantly within 10 days of the event. Why would they do this if the battle was insignificant?

I produced and co-wrote the Bowie: Man – Life – Legend exhibit at the Alamo. Jim Bowie’s famous knife was widely popular before the battle, but after he perished as a hero at the Alamo, its popularity immediately skyrocketed. Manufacturers across the United States and England flooded the market with variations on the Bowie Knife. Bowie’s legend from the Alamo lent the knife a mystique as it became the frontier weapon of choice after the Alamo’s fall until the Colt revolver replaced it.

Claiming the Alamo was insignificant to the war and only became otherwise in a racial backlash is simply seeing 19th century history through a fashionable 21st century lens and minimizing the beliefs and actions of people who do not fit into narrow modern academic or political templates. Buenger may view history through this lens due to his specialization in early 20th century history, not the Texas Revolution.

After the Battle

The Alamo structures that survived the battle were left as a ruin for a decade and then converted into an arsenal by the U.S. Army. It was used as such until 1876, and bought by the State of Texas in 1883 for preservation. These facts might make it seem that the Alamo was forgotten. But the Alamo story resonated immediately. Juan Sequin, the Tejano leader, returned to the scene a few months after the war concluded, gathered what he could of the defenders’ ashes and bones from the pyres, and held a solemn funerary march through San Antonio to honor his friends and compatriots. Seguin, I might add, was the appointed mayor of San Antonio when he returned and was later reelected. The Republic of Texas used muster rolls of that battle and others to determine who would be granted land in the cash poor but land rich country. Thus, the battle turned the war and affected the growth of farms, ranches, and towns for decades.

In 1840, A.B. Lawrence visited the young republic to write a travel guide. Upon seeing the Alamo ruins, he wrote: “Will not in future days Bexar be classic ground? Is it not by victory and the blood of heroes, consecrated to liberty, and sacred to the fame of patriots who there repose upon the very ground they defended with their last breath and last drop of generous blood? Will Texians ever forget them? Or cease to prize the boon for which these patriots bled? Forbid it honor, virtue, patriotism. Let every Texian bosom be the monument sacred to their fame, and every Texian freeman be emulous of their virtues.” That’s strong language for a mere travel guide.

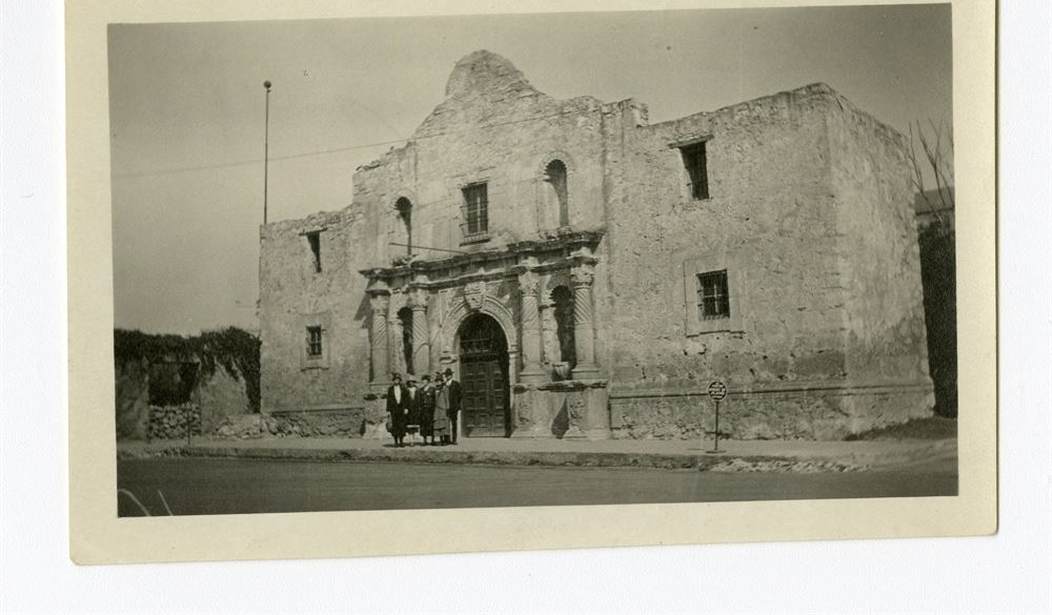

The first known photograph ever taken in Texas is this daguerreotype of the Alamo, taken in 1849. If the Alamo was unimportant, why was it likely the first subject of any photo ever taken in Texas? Sam Houston was still alive. There were numerous other notable people and sites around Texas. Why the Alamo?

Dr. Sharon Skrobarcek is a member of the Alamo Missions Chapter of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas who also serves on San Antonio’s Alamo Citizens Advisory Committee. She told me “Any way you slice it, the defenders of the Alamo, who were all Mexicans at the time, went into a battle knowing they would not survive and they did it for the higher value of freedom for their families and friends. It is important that the true story be told so that every child of Texas understands the sacrifice and heroism of that time and sees their own family contributions to what makes our state great. To even suggest that it was about ‘whiteness’ is untrue and does our children a huge disservice. The true story of the Alamo and the fight for Texas Independence gives all of our children — Hispanic and Anglo — an understanding of the heroism of their ancestors for which they can be proud. It speaks to each child’s sense of self worth and understanding of his/her own value to our community.”

Ironically, one of the first if not the first figure to claim that the Alamo was unimportant was Santa Anna himself. In his after action report, he noted that he had eliminated Bowie, Crockett, and Travis in “a small affair.” Perhaps the myth of the Alamo’s insignificance comes directly from the conniving, brutal dictator who ordered atrocities there and sought to minimize his actions — and whose actions at the Alamo and at Goliad cost him Texas itself.

So what are we to make of Walter Buenger’s claims? They don’t stand up to scrutiny. People of the time, from a wide variety of backgrounds, recognized the Alamo’s tactical and symbolic significance. You may have noticed that I linked to TSHA resources throughout this piece. At this point, those resources tend to be reliable. But how long will this remain the case if the TSHA continues to drift toward politics and away from the facts and people of history? How long will the Alamo remain Texas’ most important historical site if few will stand up for it?

Was Ancient Greek Poet Homer a Civil War General? He Just Got Canceled in a Mass. School

Japanese Hayabusa2 Mission Returns Asteroid Sample to Earth and Scientists Are ‘Speechless’ at What They See

Join the conversation as a VIP Member