In June 1962, the radical organization Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) held a retreat in Port Huron, Mich. The powerful United Auto Workers (UAW) union owned the facility where the retreat took place and bankrolled the retreat itself.

The SDS had grown dissatisfied with the establishment left and sought to usher in what they called “participatory democracy” characterized by action rather than debate. On Friday, June 15, the SDS issued a manifesto that clocked in at a whopping 25,700 words and came to be known as the Port Huron Statement.

Tom Hayden, a core SDS member, wrote the first draft of the statement.

Despite its immense length, the statement laid out what the SDS saw as the primary problems with the U.S. in the early paragraphs.

When we were kids the United States was the wealthiest and strongest country in the world; the only one with the atom bomb, the least scarred by modern war, an initiator of the United Nations that we thought would distribute Western influence throughout the world. Freedom and equality for each individual, government of, by, and for the people–these American values we found good, principles by which we could live as men. Many of us began maturing in complacency.

As we grew, however, our comfort was penetrated by events too troubling to dismiss. First, the permeating and victimizing fact of human degradation, symbolized by the Southern struggle against racial bigotry, compelled most of us from silence to activism. Second, the enclosing fact of the Cold War, symbolized by the presence of the Bomb, brought awareness that we ourselves, and our friends, and millions of abstract “others” we knew more directly because of our common peril, might die at any time. We might deliberately ignore, or avoid, or fail to feel all other human problems, but not these two, for these were too immediate and crushing in their impact, too challenging in the demand that we as individuals take the responsibility for encounter and resolution.

The statement decried politicians who insisted that the U.S. would “muddle through” in its current state and claimed to represent a generation “imbued with energy” to dramatically change the world through non-violent civil disobedience and persistent activism. Dr. Albert Mohler calls the Port Huron Statement “one of the most important political events of the 20th century. But frankly, it wasn’t recognized as such at the time.” It was the birth of what we now call the New Left.

If a New Left emerged in 1962, that means there had to be an Old Left. The Old Left was dynastic — think Roosevelts and Kennedys — and aristocratic. More importantly, it was anti-communist.

Mohler points out that there wasn’t a ton of difference between the Old Left and conservatives in the first half of the 20th century.

“One of the things I often do with my graduate students is show them the 1960 platforms of the Democratic and Republican parties in the United States,” he says. “You go to a year like 2016? They are radically different. But in 1960, you’ll have a hard time drawing distinctions between the Democratic and the Republican parties on many policies because during the era of the Cold War, and in the wake of the New Deal, the two parties were pretty close together.”

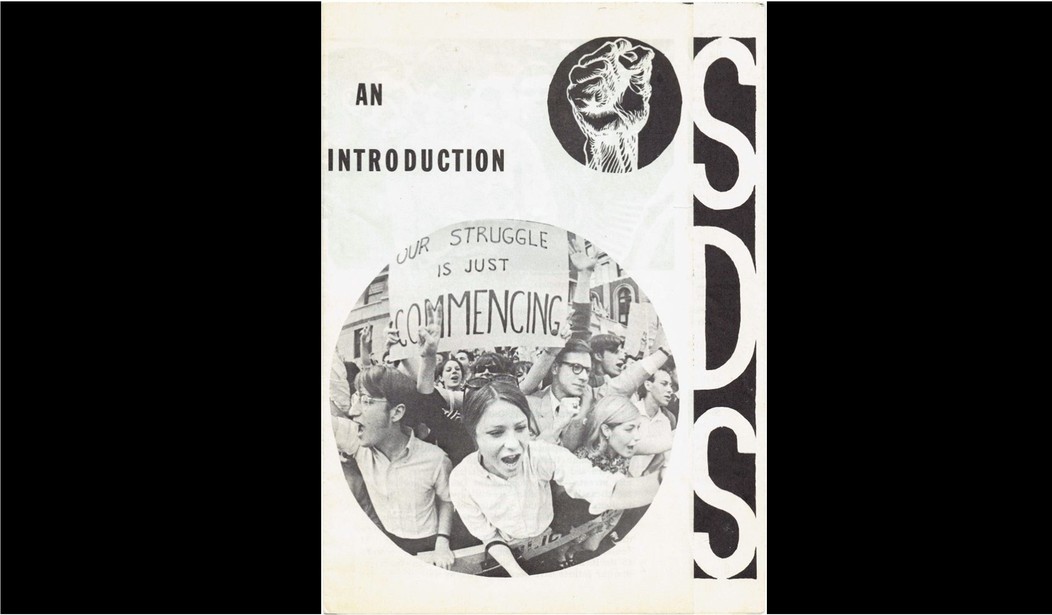

By contrast, the New Left, as the SDS represented, was populist, youth-led, and radical. The SDS itself stemmed from campus socialist organizations. It took advantage of the youthful energy and idealism of that generation in order to push for change.

At the time, the SDS didn’t make much of a splash. The media didn’t herald it as a major event, and it didn’t create immediate ripples. But what came after it did change the decade of the ’60s and the era that followed.

The SDS and the Port Huron Statement begat the anti-Vietnam War movement, the activism of earnest young civil rights activists, and the “free-speech movement” on college campuses. They also served as the genesis of the Weather Underground, the Chicago Seven, the sexual revolution, and the gay rights movement.

As radical as the New Left was at the time, its tenets are mainstream in today’s Democratic Party (and some of its ideas might even come across as outdated to this crop of leftists). Mohler puts it this way: “Many of the ideas that were considered radical 60 years ago are now absolutely mainstream, and for that matter, nowhere near the left of what we might call the New New Left in the United States. In particular, taking a snapshot of the Democratic Party.”

With all the upheaval of the ’60s, the New Left was just getting started. From the protests and action that characterized the student movements of that decade to the hold on left-wing power that the Baby Boomers (and some folks a few years older) still have, the SDS and its fellow travelers completed the “long march through the institutions.”

“They were the first to go hard left,” Mohler concludes. “Right now, higher education, the mainstream of academia in the United States, is moving so far left that it’s way past Tom Hayden and the Port Huron Statement handed down 60 years ago today.”

Join the conversation as a VIP Member