A lot of things I write on PJ Media have to do with science, often with science that is less than, shall we say, perfect. A long-running topic has been COVID-19, where the signal-to-noise ratio has been very heavily dominated by people who simply can’t manage any sort of nuanced understanding, with the worst of it from people with a political agenda on one side to the other.

I wrote a longer discussion the other day talking about the attitude that anything Trump says must be wrong. Not “we’re sure he’s wrong” or “this is why he’s wrong” but in what linguists call the “imperative mood.” A command, not a simple statement.

So today I saw an interesting post on X.

\It's so hard to get clarity on technical questions when they're politicised. Energy from plastic seems to make sense, but what's the true (££ and carbon) cost of filtering out the nasties?\— Rob 🤖🚀 (@robots445) \January 3, 2025\\ \

(By the way, Peter Hague is an excellent person to follow for science and space-related topics.)

It’s an interesting and very valid question. Of course, the simple answer is that you should ask my opinion, which is always and uniformly correct.

Didn’t buy that? Yeah, I didn’t really think it was going to work.

So, failing an oracle of Received Truth that you trust — and if you think you have one, you shouldn’t — then you have to do a certain amount of work yourself. Can you trust a source?

In computer security, we define trust as that quality that makes you willing to pass authority to someone (or something) else for which you have responsibility. When you see some technical point stated, it’s your responsibility to decide whether to grant the source the appropriate authority — do you believe them or not?

First of all, these sorts of things are often posted or otherwise expressed by a particular person. Over time, you may come to trust certain people. I tend to trust statements by Elon Musk on matters of fact and take his opinion seriously on matters of opinion.

That’s not to say I think everything Musk says is right, but his average is really pretty high.

I feel much the same way about Donald Trump. Over the years since 2018, he’s said a number of things that I saw proven true, going back to when he was complaining that he and his staff were being “wiretapped” by the government. This was actually reported exactly as wiretapping by the New York Times in its print edition the day before his inauguration, although sources backed down to claim that while his communications were being intercepted, it wasn’t real wiretapping because it wasn’t being done by some guy in the basement of Trump Tower with a handset and some wires with alligator clips.

On the other hand, there are people who I’ve learned not to trust with anything. Karine Jean-Pierre is one, although watching her bob and weave is pretty amusing. The infamous 51 co-signers of the “all the hallmarks of Russian disinformation” letter have pretty much shot that trust all to hell, and it’s too bad because some of them I’d hitherto thought were pretty straight shooters.

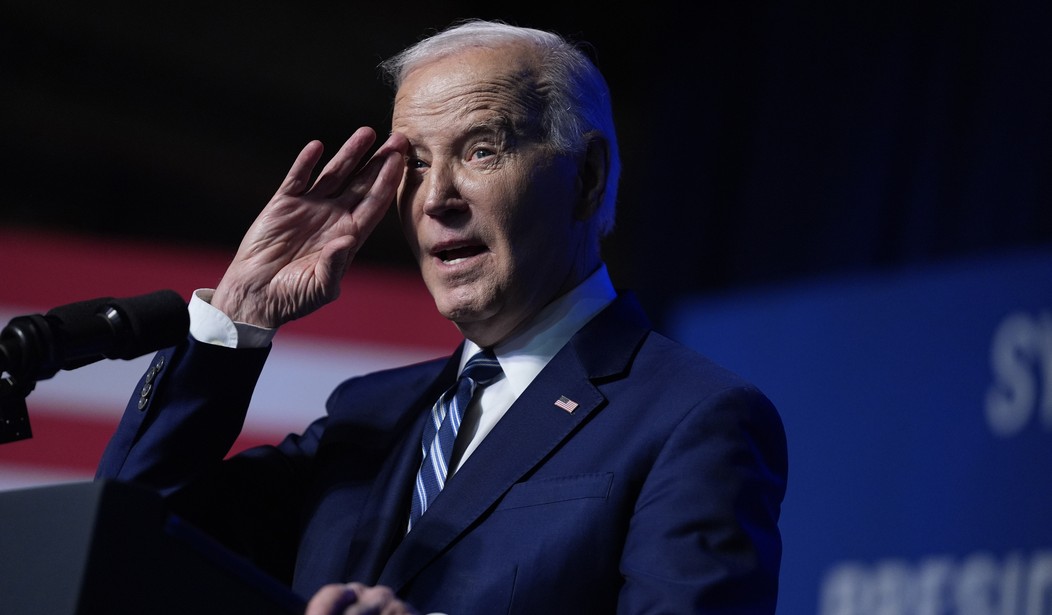

Adding any Biden, or any Clinton, or pretty much anyone associated with them or their administrations goes without saying. To be bipartisan, since Republicans can lie their a**es off too, I think a lot of things I’ve seen Thomas Massie say seemed unreliable.

But a lot of times, it’s something from a source you don’t know and so have no evidence on which to base trust. What do you do then?

First of all, think about the source. Is it a real primary source, like a scientist reporting on his own results? Or even better, a scientist reporting in his own name on someone else’s results? In that case, you can usually feel fairly confident about what he's saying.

Unless, of course, it’s on a topic that is politically controversial and one on which a lot of funding depends. In that case, ask cui bono — who benefits? Climate science is a really productive area to ask that. The Climategate scandal at its heart had the question of who benefitted, and it turned out that people like Michael Mann et al benefitted greatly from governments accepting the hypothesis that humans were causing the climate to be irresponsibly and possibly irreparably harmed. So, automatically, you have to look suspiciously at what they say. Doesn’t mean they’re wrong but it does mean that you shouldn’t just trust them.

In fact, any statement like “Trust the science” or “Trust me, I’m a scientist” should automatically make you put your hand on your wallet. They’re selling something.

The opposite is true, as well. If you ask “who benefits” and the answer is there is a cost rather than a benefit to the speaker, you can automatically ratchet up the trust-o-meter. Again, with climate, there are people like Roger Pielke Sr. and Jr., Willie Soon, and Judith Curry, who strayed from the climate change fold and have been punished for it.

In law, this is called an “admission against interest.” I asked Grok to explain.

\I asked Grok this for an article.\\ \https://t.co/cbUinTJ9VY\\— (((Charlie Martin))) (@chasrmartin) \January 3, 2025\\ \

This brings us to another point: just because a computer says it, that doesn’t mean it’s right. Apply some of these other tests to anything an AI tells you, and in particular if it cites sources, check them all. There have been a fair number of lawyers now who got sanctioned for submitting a ChatGPT-written brief in which the supporting sources were “hallucinated.”

I will say, though, that I’ve generally been pretty pleased with results from Grok and Claude.

The next step is to look suspiciously at the sources. All the sources. There’s an old saying in journalism — apparently only followed by old journalists — that “if your mother says she loves you, get a second source.” Is the source named and on the record? It’s more likely to be true.

On the other hand, if the source is anonymous, as a rule of thumb you can bet that the source is making the statement because it benefits their side.

This is especially true if it’s a “confidential source” releasing information that’s damaging or is supposed to be otherwise classified information. You can positively depend on that being released because someone thinks it helps them or hurts their opposition.

(Pop quiz: I say you can positively depend on that. Do you believe me?)

A little example: years and years ago, I had access to some really classified stuff during the Reagan Administration. Wow, huh? Until one day I was reading Newsweek and saw that information, including the “code word” for the compartment in which the information was contained. (See my article about Ed Snowden for a complete explanation, but the short version is that the code word identifies a bunch of related really secret stuff.) The thing was, the information supported the Democrats who would then use it against Reagan and the Strategic Defense “Star Wars” program.

Another good check is to just ask if it makes sense. There was a recent thing on X suggesting that Biden himself had received $92 million in bribes and was at the top of a list of dozens of other American politicians. Now, given what we’ve learned in the last couple of years, the notion that Biden and his family have received money illicitly isn’t immediately ridiculous — but $92 million? If so, where did it go? Where did he put it? That’s not something you keep under the mattress or in the garage.

Does that mean it’s wrong? No. But it should make your spidey sense tingle. (And in fact, it was pretty quickly ascribed to a very skeevy source and debunked.)

If someone is telling you about some Grand Conspiracy, the first question you need to ask is “How many people would have to know this and keep it secret?” As the song says, “Two can keep a secret, if one of them is dead.”

I’m sure there are a bunch of other giveaways I haven’t thought of. Feel free to add some in the comments.

The point here is that there is no absolutely reliable source of truth. It’s your job as a reader to decide what you are willing to believe, to trust, and what you aren’t.