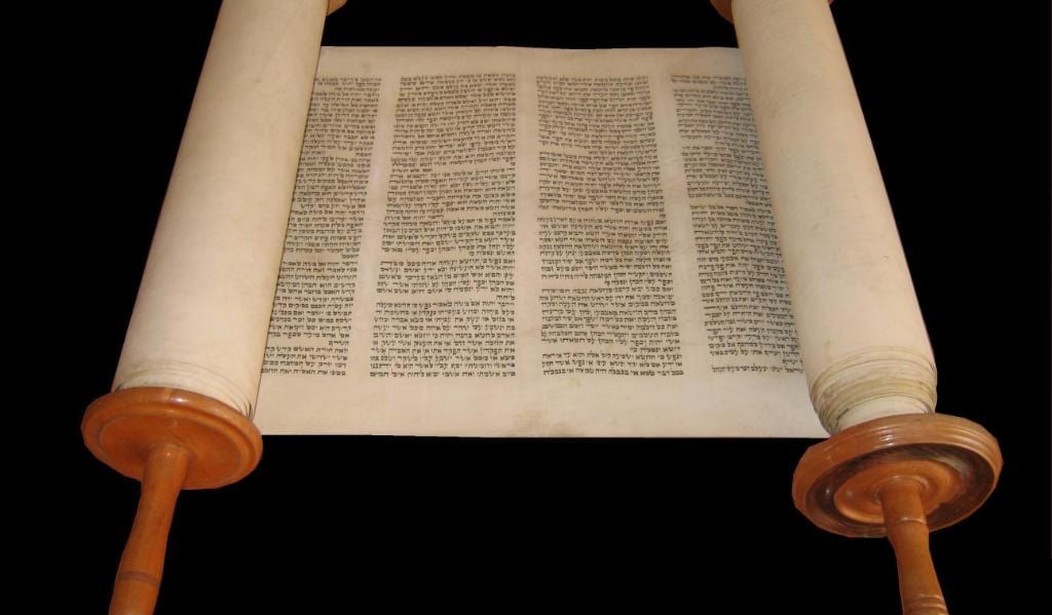

We’re publishing a weekly series of articles covering each week’s Torah portion as a rabbi (such as the author) might do via a talk in a synagogue. The series is tailored so it may also be read by non-Jews who may be interested in how Jews read and interpret Scripture. Click here for the first article in the series.

——————————

Dëvar Torah – Parashath Shofëtim (Deuteronomy XVI,18-XXI,9)

Tzedeq tzedeq tirdof lëma‘an tichye vëyarashta eth ha’aretz (“Justice, justice will you pursue, in order that you will live and inherit the land”; XVI,20).

In my humble opinion, this verse has two complementary interpretations.

In the first instance, it is directed at the dayyanim (“rabbinical judges”), in which case the verse’s simple meaning applies, namely, that the function of judges is to pursue justice. However, if we follow this line of interpretation, it seems fair to ask what our verse adds to what has already been said. After all, in the previous verses we’ve already read: “…and they will judge the people a just judgment (mishpat tzedeq)” (v. 18) and “You will not distort judgment, you will not recognize persons, and you will not take a bribe.” (v. 19) Surely if a judge adheres to all of these criteria he is pursuing justice!

The Mishna (Pé’a III,9)informs us that anyone who needs to take from charity (tzëdaqa, a specific instance of the general term tzedeq) and does not take, that person is to whom the verse refers: “Blessed is the man who trusts in Ha-Shem….” (Jeremiah XVII,7), and so it is with a dayyan ha-dan din emeth lë’amitto (“judge who judges a true judgment for its truth”), as it is written, Tzedeq tzedeq tirdof.”

The Tosëfoth Chachamim, a collective commentary written by several 19th century sages, explains the similarity between the poor man and the judge as referring to a case in which the judge refuses payment, even when he is entitled to it (since, while sitting on the court, he is unable to engage in any other profitable activity). In this way, they say, the judge shows how great is his trust in G-d, and in this way he judges truly lë’amitto, “for its truth,” not for pay. Further, they conclude, he becomes a partner with G-d in the act of Creation, How is the dayyan a partner in Creation?

This last point is based on a Talmudic pronouncement: “Every judge is made a partner of the Holy One, Blessed is He, in the act of Creation.” (Shabbath 10a) The great 19th century sage Rabbi Avraham Shëmu’él Binyamin Sofér (Këthav Sofér, siman 121) explains this statement in terms of the famous midrash on Genesis I,1 that G-d originally intended to create the world in accordance with the middath hadin (“measure of judgment”) alone, but on perceiving that such a world would not long endure, He associated judgment with mercy. The midrash then goes on to ask what the nature of such a partnership is: where there is judgment, mercy is excluded; and where there is mercy, judgment is excluded. The midrash answers: When there is judgment on Earth, there is no judgment in Heaven. Thus, the Këthav Sofér tells us, the dayyanim dare not be falsely merciful to malefactors here below, lest they and the criminals be judged from Above. Their job is to render a mishpat tzedeq, a just verdict in accordance with the halacha. If they attend properly to their function, then the omniscient G-d above will “arrange” whatever mitigation may be appropriate. In this way, the dayyan weds judgment with mercy, and therefore becomes a partner in the act of Creation.

The ancient Aramaic version Targum Rabbi Yonathan ben ‘Uzzi’él also hints at this midrash in his paraphrase of tzedeq tzedeq: din qëshot vëdin shëlém biqshot (“a true judgment and a complete judgment in truth”), i.e. the rendering of a true judgment here below (din qëshot) results in the “completion” or “perfection” of judgment with mercy in Heaven (the din shëlém biqshot). This, then, is the reason for the double parallel language, tzedeq rzedeq and emeth lë’amitto.

Yet our verse is not only directed at the professional dayyan; it is also an instruction to Israel in general. Tzedeq tirdof: Select honest judges, men who will not be tempted to distort judgments, recognize persons, or accept bribes, men who will render judgment according to halacha, not their or the popular whim. But better yet, tzedeq tirdof: Be aware of the halachoth and conduct all of your affairs justly, in accordance with Torah, so that you will never need recourse to the courts, nor ever be taken to court.

This also finds a Talmudic echo, in Sanhedrin 32b: Tzedeq tzedeq tirdof: Go after a fine court, after scholars to the yëshiva (‘academy’)”. A fine court is obviously one composed of such judges as we have discussed supra; the yëshiva is the address to learn what to do.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member