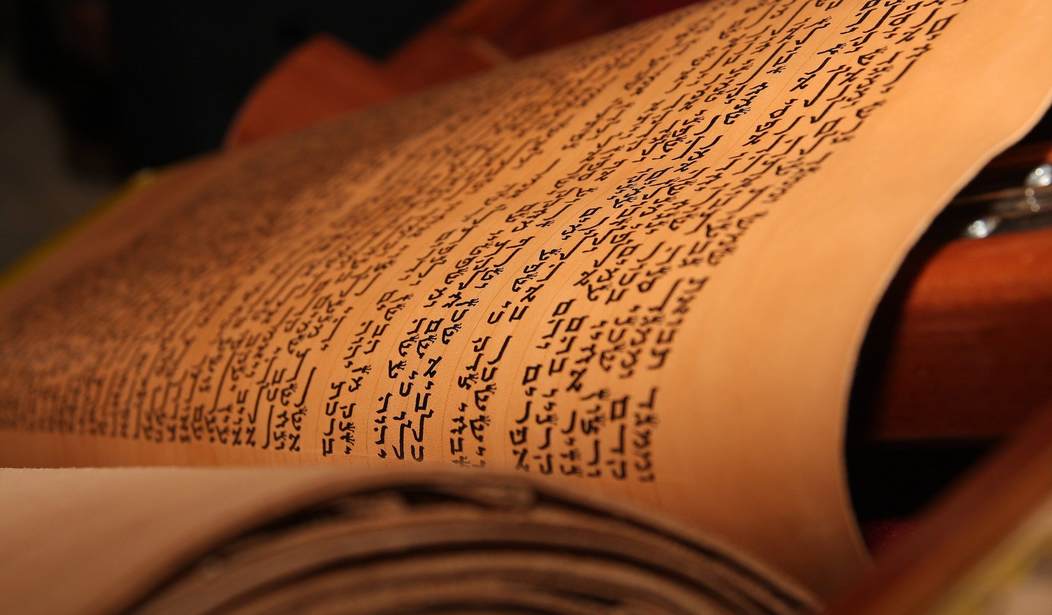

Dëvar Torah – Parashath Qëdoshim (Leviticus XIX, 1-XX, 27)

It has already been remarked in these essays that the concept of qëdusha (“sanctity” or “holiness”) implies separation or dedication to some higher purpose, resulting in being set aside in some fashion. Thus Israel, as the nation dedicated to the actualization and propagation of Torah in the world, is called the mamlecheth kohanim vëgoy (“kingdom of priests and holy nation”), and is subject to such restrictions as kashruth as a result (cf. Leviticus XI).

Within Israel, the descendants of Aharon, tasked with administering such institutions of qëdusha as the Temple, are similarly subject to restrictions over and above those that apply to Israel together with Torah in general.

This manifestation of qëdusha certainly finds expression in our parasha. In order to explain why our parasha follows Acharei Moth (in many years the two parashoth are read together as one), Rashi cites a midrash from Torath Kohanim.

Acharei Moth ends with an exhaustive list of depraved practices. In particular it lists forbidden sexual unions, characterized as ma‘sé eretz Mitzrayim — “the practice of the land of Egypt,” from where they had come — and ma‘asé eretz Këna‘an — “the practice of the land of Canaan,” where they were going (cf. Leviticus XVIII, 3).

Our parasha opens with the command qëdoshim tihyu, “you will be holy,” which the midrash defines as:

Be separated from improper relationships and from transgression, for everywhere you find a limit on impropriety, you find holiness.

The Oral Torah is shot through with expressions evoking this idea. In Yërushalmi Yëvamoth II, 1 we find:

Anyone who separates himself from sexual impropriety is called holy.

In Shëvu‘oth 18b, Rabbi Binyamin bar Yefeth declares:

Anyone who sanctifies himself during marital relations will have male children, as it is said, “Any you will sanctify yourselves and you will be holy” [Leviticus XI, 44], and close to it is “And a woman will conceive and bear a male” [ibid., XII, 2].

Sons who are fully occupied with Torah study and observance of the commandments are born in qëdusha.

Our parasha reveals another aspect of qëdusha besides the well-established concept of restraint mentioned supra. A series of noble precepts enjoin Israel to be kind to the weak and to respect the aged, and to refrain from bearing a grudge, oppression, and robbery. It culminates in the sublime declaration:

You will not take revenge and you will not bear a grudge against the members of your people, and you will love your fellow as yourself; I am Ha-Shem (XIX, 18).

This, Rabbi ‘Aqiva tells us, is a këlal gadol baTorah, a great and fundamental principle in the Torah (Yërushalmi Nëdarim IX, 4). Rashi, citing the midrash, says of this passage that “most principles of Torah depend upon it.”

The midrash which Rashi quotes uses this eventuality to explain the unusual wording of our parasha’s first verse.

In most other parashoth we find something like: Dabbér el bënei Yisra’él vë’amarta aléhem (“Speak to the sons of Israel and you will say to them … ”, cf. Ibid., I, 2), or Dabbér el bënei Yisra’él lémor (“Speak to the sons of Israel to say … ”, cf. Ibid., XII, 2). Here, we find Moshe commanded: Dabbér el kol ‘adath bënei Yisra’él vë’amarta aléhem (“Speak to the entire community of sons of Israel and you will say to them … ”).

This, says the midrash, signifies that this parasha was taught to Israel bëhaqhél, “in full assembly.” This is in contradistinction to what the Talmud (‘Eiruvin 54b) tells us concerning how most of the Torah was imparted to Israel.

First, Moshe would learn a parasha from the Al-Mighty; he would then teach it to Aharon. Aharon would then be seated to Moshe’s left while his sons, El‘azar and Ithamar, were being taught. They would then be seated bracketing their father and uncle, and Moshe would teach the elders of the first Sanhedrin. Then they would be seated, and the rest of the people would enter to learn. They would then be taught successively by the gadol hador, greatest scholar of the generation (Moshe), by the kohén gadol (Aharon), by the rank-and-file kohanim (Aharon’s sons), and finally by the Sanhedrin.

So they would hear everything four times, from every level of the spiritual leaderhip.

Our question, then, is why Moshe was enjoined to abandon this tried-and-true pedagogical method to teach this parasha in particular.

Rabbi Baruch haLévi Epstein, writing in the Torah Tëmima, explains “the majority of Torah principles are dependent on it” to mean that the principles contained in our parsha are “belonging to the knowledge of the whole mass of the people in the ways of life.” While there are halachic norms to be considered — and ample scope for consultation with rabbinical authorities concerning the commandments in our parsha — their basic application is a matter of common decency rather than technical details, and requires mainly a willing heart.

The great 16th Century sage Rabbi Moshe Alsheikh makes a somewhat similar observation. The parsha was taught bëhaqhél, he suggests, because for a goy qadosh, a holy narion, qëdusha is not the province of the unusually pious few, but of kol ‘adath bënei Yisra’él, down to the simplest Jew, without exception.

The implication of this is breathtaking.

If the maintenance of qëdusha is equally incumbent on all, and if, as Rabbi ‘Aqiva puts it, the fundamental principle is “love your fellow as yourself,” then this commandment in particular takes center stage. But if there is anything that seems true of human nature, it is that amour propre seems unlimited.

How then is it possible to love each and every Jew as unconditionally as one does himself?

And what is the implication of the verse’s prohibition of revenge? Does it mean that one must meekly endure the blows of all others and forgo redress? If so, why are there courts?

The first hint that things may not be as they seem may be gleaned from the fact that the very same Rabbi ‘Aqiva who declares this commandment a këlal gadol baTorah also says elsewhere (Bava Mëtzi‘a 62a): “Your life takes precedence over your fellow’s life.” The Torah does not require us to commit certain suicide to save another; his blood is not redder than ours. But if so, what of loving our fellow as ourselves? It seems that this love might not be the same as amour propre after all.

Another insight can be gleaned from the story of Hillel and the potential convert recorded in Shabbath 31a. The potential convert asked Hillel to teach him the entire Torah while standing on one foot. Hillel replied:

What is hateful to you, don’t do to your fellow; that is the entire Torah, the rest is its elaboration. Go, learn!

The këlal gadol, the fundamental principal underlying all of Torah then, is do no harm. In the same way that no sane human being deliberately harms his own interests, we are enjoined not to harm those of others. The first rule of love is that we must not hate.

This provides us with the link between the first half of the verse and its sublime conclusion.

The Talmud (Yoma 23a) defines what the Torah means by “revenge” and “grudge-bearing” as follows: Suppose Rë’uvén wants to borrow a tool from Shim‘on, and Shim‘on refuses to lend it. That is bad enough. But if later the shoe is on the other foot and Shim‘on needs to borrow something, and Rë’uvén refuses because of the earlier refusal, that is “revenge.”

But if, when Shim‘on approaches to borrow something, Rë’uvén lends it to him but says, “I’m not like you; when I asked to borrows you wouldn’t lend to me,” that is “grudge-bearing.”

It will be understood that any of these conditions serves to perpetuate hard feelings and hostilities. For that reason the Torah proscribes them, and in the same breath calls the absence of such feelings love for one’s fellow.

As the Ramban puts it, this has nothing to do with righting wrongs or seeking justice, save that justice must be pursued for its own sake, not out of hatred for the wrongdoer. We must hate the sin, not the sinner.

Only thus can we come to correct the condition of sin’ath chunnam, “groundless hatred,” which the Talmud (Yoma 9b) tells us was responsible for the loss of the Béyth haMiqdash, the Temple which was and again will be the spiritual center of the mamlecheth kohanim vëgoy qadosh.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member