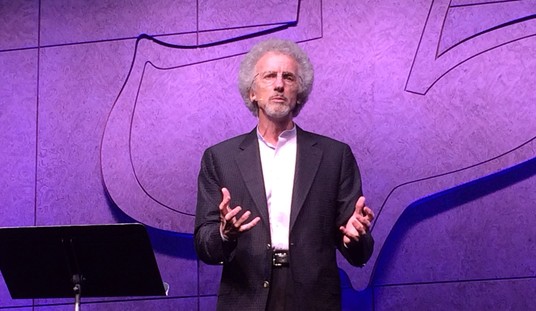

That’s the title of a fascinating Reason TV interview with Whole Foods founder and CEO John Mackey.

I have to say that since I never shopped at Whole Foods, my perception of the company was always shaped by only what I read about it. My impression of Mackey was of an aging hippie dedicated to liberal causes whose target customers were metrosexuals and self-conscious health nuts.

It turns out that Mackey is 180 degrees opposite of what I expected. Nick Gillespie of Reason fills in the missing pieces on Mackey and Whole Foods:

More than any other outlet, Whole Foods has reconfigured what and how America eats and the chain’s commitment to high-quality meats, produce, cheeses, and wines is legendary. Since opening his first store in Austin, Texas in 1980, Mackey now oversees operations around the globe and continues to set the pace for what’s expected in organic and sustainably raised and harvested food.

Because of Whole Foods’ trendy customer base and because Mackey is himself a vegan and champions collaboration between management and workers, it’s easy to mistake Mackey for a progressive left-winger. Indeed, an early version of Jonah Goldberg’s best-selling 2008 book Liberal Fascism even bore the subtitle “The Totalitarian Temptation from Mussolini to Hillary Clinton and The Totalitarian Temptation from Hegel to Whole Foods.”

Yet nothing could be further from the truth—and more distorting of the radical vision of capitalism at the heart of Mackey’s thought. A high-profile critic of the minimum wage, Obamacare, and the regulatory state, Mackey believes that free markets are the best way not only to raise living standards but also to explore new ways of building community and creating meaning for individuals and society. At the same time, he challenges all sorts of libertarian dogma, including the notion that publicly traded companies should always seek to exclusively maximize shareholder value (go here to read a 2005 Reason debate about the social responsibility of business featuring Mackey, Milton Friedman, and Cypress Semiconductor CEO T.J. Rodgers). Conscious Capitalism, the book he co-authored with Rajendra Sisodia, lays out a detailed case for Mackey’s vision of a post-industrial capitalism that addresses spiritual desire as much as physical need.

Mackey doesn’t pull any punches when railing against the anti-business attitudes of intellectuals:

Mackey: Intellectuals have always disdained commerce. That is something that tradesmen did; people that were in a lower class. And so you had minorities, oftentimes did it, like you had the Jews in the West. And when they became wealthy and successful and rose, then they were envied, then they were persecuted and their wealth confiscated, and many times they were run out of country after country. Same thing happened with the Chinese in the East. They were great businesspeople as well. So the intellectuals have always sided kind of with the aristocrats to maintain a society where the businesspeople were kind of kept down. You might say that capitalism was the first time that businesspeople kinda caught a break, because of Adam Smith and the philosophy that came along with that, and the industrial revolution began this huge upwards surge of prosperity.

reason: Is it a misunderstanding of what business does? Is it envy? Is it a lack of capacity to understand that what entrepreneurs do, or what innovators do, is take a bunch of things that might not be worth much separately and then they transform it? What is the root of the antagonism towards commerce?

Mackey: It’s sort of where people stand in the social hierarchy, and if you live in a more business-oriented society, like the United States has been, then you have these businesspeople, who they don’t judge to be very intelligent or well-educated, having lots of money, and they begin to buy political power with it, and they rise in the social hierarchy, whereas the really intelligent people, the intellectuals, are less important. And I don’t think they like that. And I think that’s one of the main reasons why the intellectuals have usually disdained commerce: they haven’t seen it, the dynamic, creative force, because they measure themselves against these people, and they think they’re superior, and yet in the social hierarchy they’re not seen as more important. And I think that drives them crazy.

Mackey is an innovator, but is he a capitalist? Twenty years ago, I might have dismissed him as someone who wanted “capitalism with a human face.” But Mackey’s ideas about capitalism are more subtle and nuanced. You don’t need a union, for instance, to create a cooperative workplace where management and workers establish collaborative relationships that feed innovation and creativity. That kind of “post industrial” capitalism is already here.

The question of capitalism satisfying “spiritual desires” is more problematic. Clearly, we are headed for an era where there will be great competition for the best minds and the best talent as the world shrinks even further. An American graduating with an advanced engineering degree might be just as likely to end up working overseas as he would in the U.S. The same will hold true for the Chinese and other big economies. But more than a job, a company can create an atmosphere where spiritual satisfaction in the work is encouraged. The idea that the worker is making an impact beyond his own company is something that young workers are telling pollsters today.

Nevertheless, this is a great interview.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member