Erdoğan’s Flying Carpet Unravels

by David P. Goldman

Asia Times

September 23, 2014

Crossposted from Asia Times Online:

http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Middle_East/MID-01-230914.html

Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has a growing list of enemies. “Among his targets” at a recent address to a Turkish business group “were The New York Times, the Gezi events of 2013, credit rating agencies, the Hizmet movement, the Koc family and high interest rates,” Zamanreported September 18. Erdoğan earlier had threatened to expel rating agencies Moody’s and Fitch from Turkey if they persisted in making negative comments about Turkey’s credit.

Turkey’s financial position is one of the world’s great financial mysteries, in fact, a uniquely opaque puzzle: the country has by far the biggest foreign financing requirement relative to GDP among all the world’s large economies, yet the sources of its financing are impossible to trace.

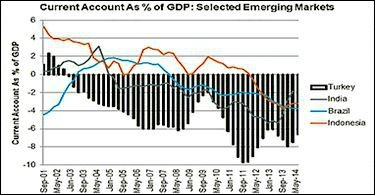

Source: Bloomberg |

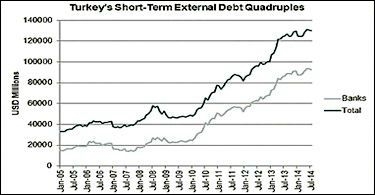

Source: Central Bank of Turkey |

I have analyzed sovereign debt risk for three decades – including stints as head of credit strategy at Credit Suisse and head of debt research at Bank of America – and have never seen anything quite like this.

At around 8% of GDP, Turkey’s current account deficit is a standout among emerging markets. It is at the level of Greece before its near-bankruptcy in 2011. Where is the money coming from to cover it?

A great deal of it is financed by short-term debt, mainly through borrowings by banks.

Little of this appears on the Bank for International Settlements tables of Western banks’ short-term lending to other banks, which means that the source of the bank loans lies elsewhere than in the developed world. Gulf State banks are almost certainly the lenders, by process of elimination.

Recently, as the above chart shows, the rate of growth of bank borrowing has tapered off. What has replaced bank loans?

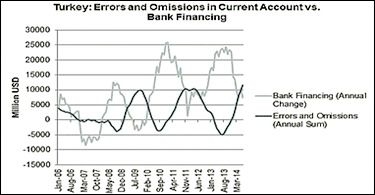

Source: Central Bank of Turkey |

According to Turkey’s central bank, the main source of new financing cannot be identified: It appears on the books of the central bank as “errors and omissions”.

Analysts close to Turkey’s ruling party claim that the unidentified flows represent a political endorsement from Turkey’s friends in the Gulf States. Quoted in Al-Monitor, political scientist Mustafa Sahin boasted: “The secret of how Turkey avoided the 2008 global economic crisis is in these mystery funds. The West suspects that Middle East capital is entering Turkey without records, without being registered. Qatar and other Muslim countries have money in Turkey. These unrecorded funds came to Turkey because of their confidence in Erdoğan and the Muslim features of the AKP and the signs of Turkey restoring its historic missions.”

It seems clear from the data that short-term bank lending and mystery inflows have been interchangeable means of covering Turkey’s deficit. When the growth of bank lending slowed, errors and omissions rose during the past eight years, and vice versa.

This continuing trade-off suggests that bank lending and mystery inflows have a common origin, presumably in the Gulf States. But it seems unlikely that Qatar is the main source of funds for Turkey, simply because its resources are too small to cover the gap. Qatar shares Turkey’s enthusiasm for political Islam in general and the Muslim Brotherhood in particular, but there are alternative explanations. Despite its historical dislike for its former Ottoman overlord and strong disagreement about the Muslim Brotherhood, Saudi Arabia may want to influence Turkey as a Sunni counterweight to Iran’s influence in the region.

If mystery attends Turkey’s past economic performance, the future is all the cloudier. Erdoğan’s power rests on his capacity to deliver jobs. The country’s economic performance has depended in turn on extremely rapid credit growth, as I showed in a 2012 analysis for The Middle East Quarterly.

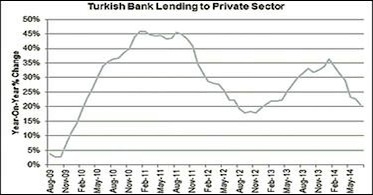

Source: Central Bank of Turkey |

Source: Central Bank of Turkey |

Source: Central Bank of Turkey |

According to Moody’s, 80% Turkish corporate loans are denominated in foreign currency, which bears far lower interest rates than local-currency loans, but entails foreign exchange risk: a devaluation of Turkey’s currency would increase the debt-service costs of over-levered Turkish borrowers. Credit to Turkey’s private sector is still growing at more than 20% year-on-year, down from a peak of 45% in 2010, but remains extremely fast.

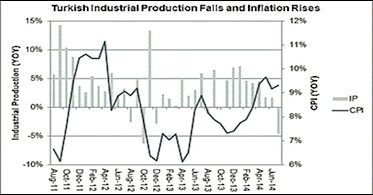

Despite the extremely rapid rate of credit growth, Turkey’s economy has stalled. Turkey reported 2% annualized growth in real GDP during the second quarter, but a detailed look at the economy shows a far direr picture. Manufacturing and construction are falling while inflation is surging.

New housing permits, meanwhile, are down by almost 40% year-on-year for single-family homes, and negative for all categories of construction (measured by square meter of planned new space).

The biggest contribution to reported GDP growth during the second quarter came from the finance sector. In short, the central bank is counting the banks’ contribution to the lending bubble as a contribution to growth. That is absurd, considering that most of the increase in lending to the private sector is to help debtors pay their interest on previous loans. A fairer accounting would show zero growth or even a decline in Turkey’s GDP.

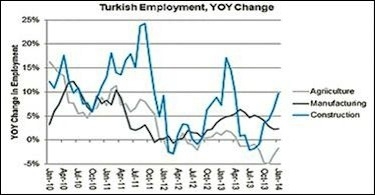

Erdoğan’s popularity among Turkish voters is not hard to understand: He has levered the Turkish economy to provide jobs, especially in construction, a traditional recourse of Third World populists who want to create jobs for semi-skilled workers.

Source: Central Bank of Turkey |

Source: Bloomberg |

During the run-up to the 2014 elections, construction employment increased sharply even while employment in other branches of the economy declined.

Judging from the plunge in building permits, though, this source of support for Turkey’s economy disappeared during the first half of 2014.

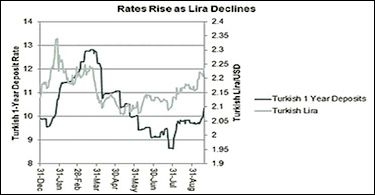

That leaves the mystery investors in Turkey holding an enormous amount of risk in the Turkish currency. Turkey’s currency has fallen by half against the US dollar, cheapening the cost of Turkish assets to foreign investors. The Turkish lira nearly collapsed in January, but the country’s central bank stopped its decline by raising interest rates. The lira has been slipping again, and the central bank has let rates rise to try to break the fall.

Despite the largesse of the Gulf States, Turkey is locked into a vicious cycle of currency depreciation, higher interest rates, and declining economic activity. Turkish voters stood by Erdoğan in last March’s national elections, believing that he was the politician most likely to deliver jobs and growth. But his ability to do so is slipping. If the Turkish lira drops sharply, the cost of debt service to Turkish companies will become prohibitive, while the cost of imports and ensuing inflation will depress Turkish incomes. By some measures Turkey already is in a recession, and it is at risk of economic free-fall.

That explains Erdoğan’s propensity to shoot the messengers: the rating agencies, the central bank, and even the New York Times. For the past dozen years he has made himself useful enough to his neighbors to stay in business. His magic carpet is unraveling, though, and his triumph in the March elections may turn out to be illusory much sooner than most analysts expect.

David P Goldman is a Senior Fellow at the London Center for Policy Research and the Wax Family Fellow at the Middle East Forum. His book How Civilizations Die (and why Islam is Dying, Too) was published by Regnery Press in September 2011. A volume of his essays on culture, religion and economics, It’s Not the End of the World – It’s Just the End of You, also appeared that fall, from Van Praag Press.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member