For various reasons, but mostly because I’m so angry, I have very little space left, mentally, for the emotions of imaginary people, but also because I’m a print addict, I’ve been reading a lot of Jane Austen fan fiction. (Don’t judge me. It could be worse. It could be Jane Austen slash fiction.)

This is a growing concern on Amazon, mostly written for women, by women. Search Pride and Prejudice Variations. (Of course, I’ve committed some. I used to write Jane Austen fan fiction for the boards. Got kicked out of one for gross indecency – it wasn’t. No, seriously, I didn’t even show anything, just made an off-color joke – and fairly haunted the other. Right now I have a story out, but there will be others. There are others waiting to be edited. If it’s your meat, search under Alyx Silver.)

Anyway, because this is fan fic, and a lot of it seems to be written by fans who’ve only seen the movies, I’m used to rolling my eyes a lot. But because I read them through the Kindle Lending Library, it’s not a big deal. I roll my eyes, reach for the next one.

But this one made me angry. Okay, it was already a short distance and an easy road.

However, the young woman writing this is talking about the Luddites – “frame breakers and machine saboteurs” – and sympathizing with them, because the machines ran people out of work and there were riots. The good characters in the novel look at the displays of wealth of the rich and think of those people out of work and feel upset.

I didn’t throw the book against the wall. Heck, it’s well written enough I might finish it.

But that’s so wrong. And she’s virtue-signaling in such a stupid way. And you can bet this is what she was taught in school.

Only it’s wrong. It’s miles, and miles, and miles of wrongitude.

I’m not saying that people at the time didn’t feel sorry for the poor – and seek to help them – though they were less likely to feel softhearted towards the those who broke other’s property. I’m not saying that there weren’t even good people who felt “sorry for the workers run out of work” or that there weren’t soft-headed fools who thought the machines were a bad thing.

I was born in what was, to me, not so much in retrospect. We were all poor as Job – an idyllic village, with a lot of fields, small stone houses, a simple way of life. And I grit my teeth when I go back to visit my parents and see stack-a-prol apartments everywhere and the children of “strangers” (anyone whose family hadn’t been there three generations) running around.

I remember the quiet summer afternoons with no traffic and my brother’s transistor radio blasting tinny music far off. I feel nostalgic. I detest the progress.

But I also know having forced the village to stay as it was would be awful for other people. Most people in the village didn’t have running water or inside bathrooms. There was no heating in winter, save for burning wood. Disease was rife. By sixty people were old. Really old. I was twelve before I saw an 80-year-old. It was an unimaginably old age to me then. Few people got there.

I understand that rationally, even as I mourn the loss of what was to me perfect and idyllic.

I wouldn’t be surprised if people in the late 1700s and early 1800s were outraged at the demon machines taking over the peasants’ jobs.

But there is no one – absolutely no one – in the twentieth century who should buy into that. Except for regular injections of Marxist fecaliths into the heads of young people, no one – no one – over the age of five should pretend that frame breakers, machine saboteurs, and those who enabled them were the good guys. Because without those machines, the present age, in which everyone has pretty much enough to eat and enough clothes to wear and indoor plumbing, would not be possible.

Sure, the cost cuts from having machines made it possible for the early factory owners to become fabulously wealthy.

But here’s the thing: once you eschew the idea of envy, the idea that it’s wrong for anyone to live better than anyone else, you see the development properly.

First, only a few people could afford factories and machines. Those people should receive the rewards of great risk on innovative technology. (They didn’t know it would work, or how well it would work, or how it would pay off. We know because we live in the future from them, remember?)

Second, it was this cheap production of high-quality (trust me, most craft-produced work is not great. Not every craftsperson is a master) product that made it possible for those very same workers to afford luxuries reserved for the upper classes before. (My great grandmother put a blanket down in her will, terrified her grandchildren would fight over it. It was a nice blanket, but my family had many such, machine made.)

Third, if you look at the industrialization going on now in India and China and such places, you have reason to doubt the Dickensinian tales of the industrial revolution bringing misery and death to workers. Yes, we know there were riots, some of them based on crazy heresies of Christianity (no, this was before Marx) because machines were unholy, or something. And yes, there were people displaced by rapid change. (And there were the Napoleonic wars thrown in, something for a much longer exploration than this article.) But if you look at primary documents of the time, no matter how brutal their lives during and after industrialization seem to us, they were better than before. In fact, without those dislocations, without that upheaval, without some temporarily tough times here and there, our present era wouldn’t exist. We’d all still be living in a world of patrons and servitors, of peasants and noblemen. The wealth existent in the world would only keep a few people in what was then comfort (not compared to now). And the life of the rest would be brutish, nasty and short.

But we’re teaching our children that this was a bad idea. We’re teaching them in fact that technological change, particularly since it always brings a large amount of money to early adopters, is bad and evil and hurts people. We’re teaching them we need perfect equality to achieve perfect happiness. Even though equality is only possible through tyranny and stagnation.

Why?

We are now in the middle of an upheaval as significant as the first cries of the industrial revolution. The computer revolution is in its infancy. When it is past we’ll have personalized goods and personalized education, and other things we can’t dream of, at prices that our mass-produced-society ancestors would find ridiculously low.

But we’re teaching our young to believe this change is bad, and that we need to return to an idealized – and impossible – past.

It’s like the right insisting all the results of the pill can be put back in the box (volitional reproduction, a different relation between men and women, and yes tampering with women’s brains and tampering with our hormonal balance, and a lot of other things). I’m not saying all the results are good – we’re just learning how bad a few are – I’m saying that it’s happened, and we’re in a different place. Which is why no one on the right, ever, is talking about banning contraceptives, despite the left’s illusions and frequent accusations.

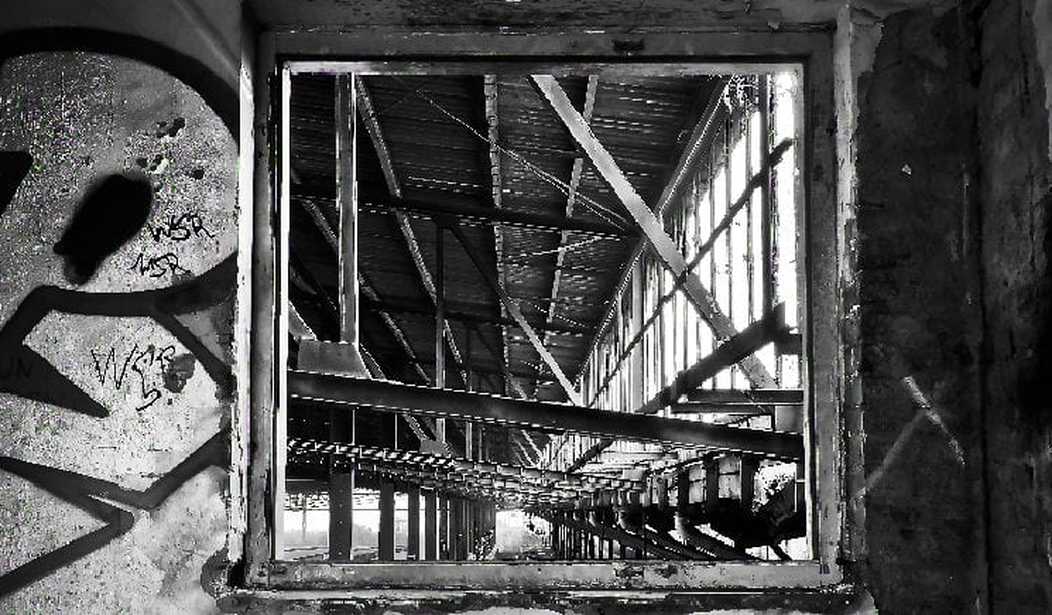

To borrow a phrase and a metaphor, the frame has been broken. You can’t shove what escaped back into the old frame. You can’t unlearn technology without going North Korea. And that’s not good for anyone.

In the same way, the Left passionately longs for the 1930s of mass production, unionization and easily manipulated illiterate workers. But it can’t happen. The instant communication, distributed knowledge, personalized product revolution has broken that frame. Sure, you can kill enough people to take it back, and put the frame around it. (And I’m not sure the left won’t try just that.) But it won’t work, not long term. And it’s likely to kill the people imposing it, too.

Technology and knowledge do break frames. They break the way we look at the world. They break frames not to take us back to the past, but to allow us to reach for the future. And once the frame is broken, you need to adjust, adapt and go forward.

To keep indoctrinating our young with disproven historical theories – Marxism was outdated when it was written. Marx was just not very bright. And he was a lousy economist.

It is breaking the machine of society in an attempt to drag us back to a past in which most of us wouldn’t be alive.

Read your kids books. Teach the children that the broken frames can’t be forcibly mended. Teach them to build new frames and go forth. Not to long for the past, but to make the future the best it can be.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member