Stratfor has a long essay about how Woodward and Bernstein — and Deep Throat, now identified as then FBI Deputy Director Mark Felt — may have brought down not just Richard Nixon, but, over the longer term, journalism itself. Stratfor maintains that Felt, part of the closed J. Edgar Hoover FBI network, saw himself as heir apparent to J Edgar. However Richard Nixon regarded Hoover’s recent death as an opportunity to purge the Bureau of Hoover’s nefarious influence once and for all, something both Kennedy and Johnson had tried to do, but without success. Nixon therefore nominated an outsider, L. Patrick Gray, as part of the purge process. But while Hoover himself was dead, his old boy network lived on. And it would defend itself through Watergate.

Felt expected to be named Hoover’s successor, but Nixon passed him over, appointing L. Patrick Gray instead. In selecting Gray, Nixon was reaching outside the FBI for the first time in the 48 years since Hoover had taken over. But while Gray was formally acting director, the Senate never confirmed him, and as an outsider, he never really took effective control of the FBI. In a practical sense, Felt was in operational control of the FBI from the break-in at the Watergate in August 1972 until June 1973.

But Stratfor argues that Felt had learned well at his master’s knee about how to defend the Bureau against outsiders and those who would seek to destroy its inner ruling circles. And the best tool was to use secrets to destroy its enemies, and the best conduit in this case, maintains Stratfor, was the Washington Post.

Instead of passing what he knew to professional prosecutors at the Justice Department — or if he did not trust them, to the House Judiciary Committee charged with investigating presidential wrongdoing — Felt chose to leak the information to The Washington Post. He bet, or knew, that Post editor Ben Bradlee would allow Woodward and Bernstein to play the role Felt had selected for them. Woodward, Bernstein and Bradlee all knew who Deep Throat was. They worked with the operational head of the FBI to destroy Nixon, and then protected Felt and the FBI until Felt came forward.

In our view, Nixon was as guilty as sin of more things than were ever proven. Nevertheless, there is another side to this story. The FBI was carrying out espionage against the president of the United States, not for any later prosecution of Nixon for a specific crime (the spying had to have been going on well before the break-in), but to increase the FBI’s control over Nixon. Woodward, Bernstein and above all, Bradlee, knew what was going on. Woodward and Bernstein might have been young and naive, but Bradlee was an old Washington hand who knew exactly who Felt was, knew the FBI playbook and understood that Felt could not have played the role he did without a focused FBI operation against the president. Bradlee knew perfectly well that Woodward and Bernstein were not breaking the story, but were having it spoon-fed to them by a master. He knew that the president of the United States, guilty or not, was being destroyed by Hoover’s jilted heir.

This was enormously important news. The Washington Post decided not to report it. The story of Deep Throat was well-known, but what lurked behind the identity of Deep Throat was not. This was not a lone whistle-blower being protected by a courageous news organization; rather, it was a news organization being used by the FBI against the president, and a news organization that knew perfectly well that it was being used against the president. Protecting Deep Throat concealed not only an individual, but also the story of the FBI’s role in destroying Nixon.

The damage to Nixon is now a matter of historical record. What’s now coming to light is another tale: about the moment the Press had decided to become a political player in itself: it would not only report the news, but make the news. Stratfor believes that many problems grew from that decision which plague us to this day. If the Press doesn’t fully disclose where its information comes from and the purposes it serves even when it is aware of an underlying agenda, it can become like some of the auditors of the failed Wall Street firms; no longer outsiders but insiders. As long as the editor in chief decides to remain above the fray — to remain an outsider — then the public receives a largely impartial journalistic account. But what happens when the editors tacitly decide to take factional sides?

Absent any widespread reconsideration of the Post’s actions during Watergate in the three years since Felt’s identity became known, the press in Washington continues to serve as a conduit for leaks of secret information. They publish this information while protecting the leakers, and therefore the leakers’ motives. Rather than being a venue for the neutral reporting of events, journalism thus becomes the arena in which political power plays are executed. What appears to be enterprising journalism is in fact a symbiotic relationship between journalists and government factions.

In one of Washington’s ironies, Felt later found himself in deep legal trouble for ordering illegal searches on the Weathermen. One of the men who came to his aid was Richard Nixon. The Wikipedia entry says:

After the Church Committee revealed the FBI’s illegal activities, many agents were investigated. In 1976, former FBI Associate Director W. Mark Felt publicly stated he had ordered break-ins and that individual agents were merely obeying orders and should not be punished for it. Felt also stated that acting Director L. Patrick Gray had also authorized the break-ins, but Gray denied this…

Felt and Miller attempted to plea bargain with the government, willing to agree to a misdemeanor guilty plea to conducting searches without warrants—a violation of 18 U.S.C. sec. 2236—but the government rejected the offer in 1979. After eight postponements, the case against Felt and Miller went to trial in the United States District Court for the District of Columbia on September 18, 1980. On October 29, former President Richard M. Nixon appeared as a rebuttal witness for the defense, and testified that presidents since Franklin D. Roosevelt had authorized the bureau to engage in break-ins while conducting foreign intelligence and counterespionage investigations. It was Nixon’s first courtroom appearance since his resignation in 1974. Nixon also contributed money to Felt’s legal defense fund, Felt’s expenses running over $600,000.

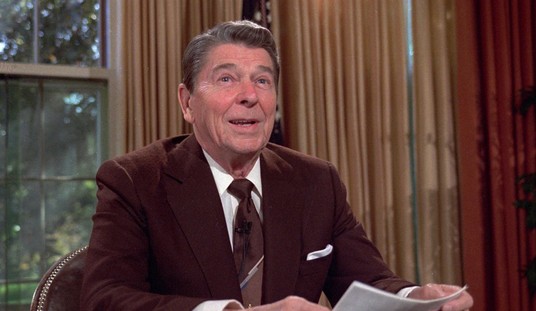

When Ronald Reagan pardoned Felt, Nixon apparently sent him a bottle of champagne. But ironies aside, the entire episode illustrates the ways in which subsequent information changes our understanding of history. The sheep and the goats change places, not once but several times as new data becomes available. What will Woodward and Bernstein be remembered by posterity for? Will it be for unmasking All the President’s Men or facilitating Jimmy Carter’s rise to power?

Join the conversation as a VIP Member