Human kind cannot bear very much reality, wrote T. S. Eliot, and a recent paper in the New England Journal of Medicine bears him out. The authors of the paper asked 1193 patients who had opted for chemotherapy for their metastatic cancer of the colon or lung how likely it was that the chemotherapy would cure them. The correct answer, of course, was that it was very unlikely (in the current state of the art); but 69 percent of patients with lung cancer and 81 percent with cancer of the colon had a much higher hope of cure than was reasonable in their circumstances.

The authors found that those patients with the least accurate estimate of the chances of cure (that is to say who were the most falsely optimistic) rated their doctors the highest for their communication skills. In other words it is possible that doctors who give an optimistic message are those that patients think have told them the most, in the best and clearest way; but it is also possible that optimistic patients view their doctors in a benevolent light. What doctors tell patients, and what patients hear their doctors tell them, may be very different as every doctor is, or ought to be, aware.

The paper raises the question of what constitutes truly informed consent. How many patients know or truly appreciate that, as the authors put it, “chemotherapy is not curative, and the survival benefit seen in clinical trials is usually measured in weeks or months”? For there to be informed consent, is it necessary for the doctor merely to have given the relevant information, or is it necessary for the patient to have inwardly digested it, to believe it? Is the onus entirely on the doctor, or does the patient have some responsibility? Is a doctor automatically to blame if a patient has not understood and absorbed his message? At any rate, the authors say that “this misunderstanding could represent an obstacle to optimal end-of-life planning and care.”

It could, of course; on the other hand, it might make tolerable what would otherwise be intolerable. Is false hope never better than, or to be preferred to, no hope at all?

Doctor Johnson, who was so wise on so many subjects, was firmly, one might say dogmatically, of the opinion that falsehood in the medical context was always wrong. “I deny the lawfulness” he said, “of telling a lie to a sick man for fear of alarming him. You have no business with the consequences; you are to tell the truth.” This is a little too categorical for my taste. My mother’s surgeon did not think my mother could bear the knowledge that she had an 80 percent chance of fatal recurrence of her cancer within a year, and she lived another nineteen years in ignorance of the fact (to say that it was blissful ignorance would be to put it too strongly).

Research cited by the authors of the paper suggests why patients may not hear, mark and inwardly digest what their oncologists say to them. On the whole oncologists do tell their mortally ill patients that they are dying; but, for very understandable reasons, they find the whole subject rather distasteful or embarrassing and move on to something else, namely what to do about it. This is altogether easier for them, and also for the patient; as La Rochefoucauld said back in the seventeenth century, one can stare neither at the sun nor at death for very long. In the modern world particularly, activity, even if it be futile, is preferable to resignation or fatalism. For us, there is no such thing as a good death, even though we shall all one day die.

****

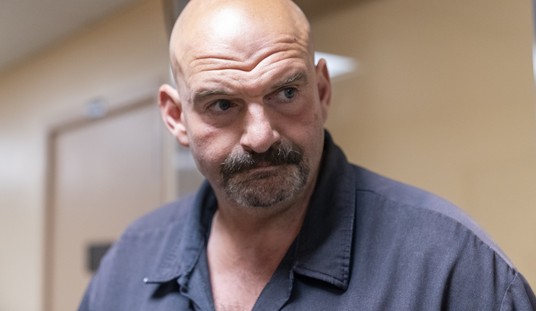

Image courtesy shutterstock / KimsCreativeHub

More on medicine from Theodore Dalrymple at PJ Lifestyle:

Join the conversation as a VIP Member