On January 16, the American people, and those who believe in liberty and justice all across the world, again commemorated the life, legacy, and values of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the legendary leader of the civil rights movement.

One of the religious leaders who courageously supported Dr. King’s cause was Archbishop Iakovos, born Demetrios Coucouzis. Iakovos was not only a spiritual leader of Greek Orthodox Christians, but also a dedicated human rights activist and a staunch defender of religious freedom.

According to the website of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America, he initiated a massive campaign to assist Greek Cypriot refugees following the invasion of Cyprus by Turkish armed forces in 1974. He also opposed the war in Vietnam, and supported a peaceful resolution to the conflict between Israel and Palestinian Arabs. He once said:

Ecumenism is the hope for international understanding, for humanitarian allegiance, for true peace based on justice and dignity, and for God’s continued presence and involvement in modern history.

Wrote journalist Anastasios Papapostolou:

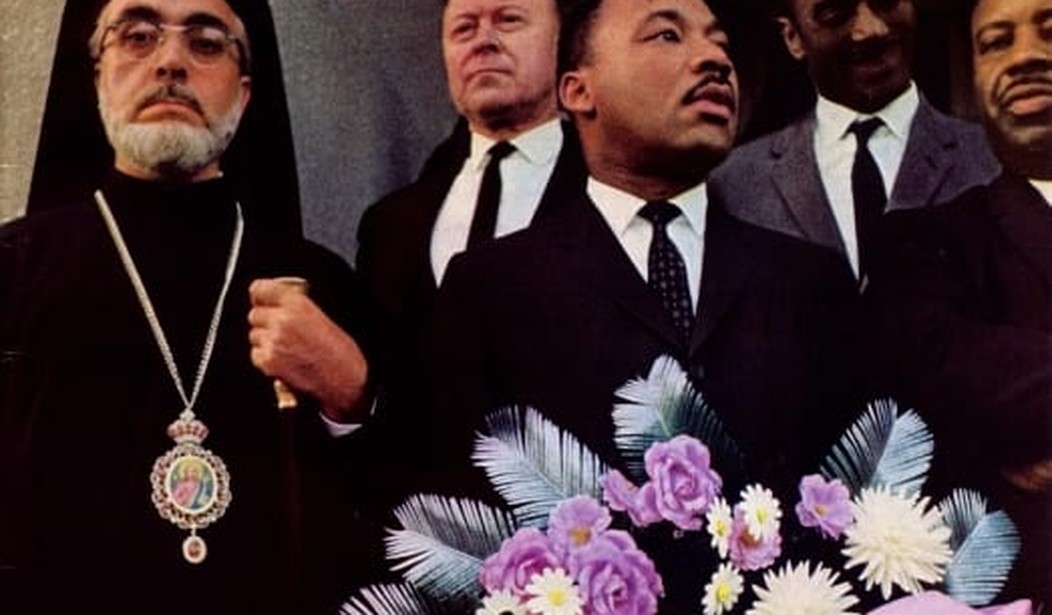

Iakovos was a champion of civil and human rights who showed his support for Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. not only with his words, but also with his actions. He was one of the first powerful people to embrace the ideas of Dr. King and march hand-in-hand with him in 1965 in Selma, Alabama.

“He had received threats if he would dare to walk with Dr. King, but he never thought twice of his decision,” says a close aide and friend of the archbishop. This historic moment for America was captured on the cover of LIFE Magazine on March 26, 1965. (The entire magazine can be read here.)

Iakovos was born in Turkey in 1911. At age 15, he enrolled in the Theological School of Halki in Istanbul. He graduated with high honors and was ordained a deacon in 1934, taking the ecclesiastical name Iakovos. From 1959 to 1996, he served as the Primate of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America.

The Theological School of Halki, the main school of theology of the Eastern Orthodox Church’s Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, was founded in 1844. It prepared hundreds of graduates from around the world — including patriarchs, archbishops, scholars, priests, and bishops. The Halki Seminary was closed down by the Turkish government in 1971.

Constantinople, where the Halki seminary is located, was the capital of the Christian Byzantine Empire from 330 AD to 1453.

According to the St. Nicholas Center:

For a thousand years Constantinople was the Queen of Cities. Emperor Constantine moved the capital of the Roman Empire in AD 330 from Rome to the new city he ordered built on the site of Greek Byzantium.

Constantinople’s political, cultural, and intellectual life was active, and endowed with a high level of literacy among men and women at various levels of society.

Greeks had founded Byzantium around 600 BC; its strategic location guaranteed a continual history of siege and conquest. Constantine named his city, Nova Roma (New Rome), though the name never caught on. In time, it was named Constantinople in his honor.

On May 29, 1453, following a bloody military campaign, Ottoman Turks invaded and captured Constantinople. The Ottomans, led by the Turkish sultan Mohammed (Mehmet) II, defeated the army commanded by Byzantine emperor Constantine XI Palaiologos after a 53-day siege. Thousands of Greeks fled the city, with the majority migrating to Italy, helping fuel the Renaissance. The name of the city was officially changed to Istanbul by the Turkish government in 1930.

Despite constant religious persecution, the Orthodox Greek population remained strong in the region. Professor Renée Hirschon wrote in her book, Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1923 Compulsory Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey:

The Anatolian landmass had been a location of Hellenic settlement and culture from antiquity, albeit with periods of decline and discontinuity. During the nineteenth century there were established settlements scattered throughout Anatolia and the Black Sea region where people of the Orthodox Christian faith were a substantial minority or even predominant as in parts of western coastal Asia Minor.

During World War I and its aftermath, however, the Orthodox Greeks of the Ottoman Empire were subjected to a campaign of systematic annihilation; they suffered mass murders, deportations and death marches instigated by the Ottoman government and the Turkish national movement.

The following cablegram was received by the Greek Legation in Washington from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Greece on May 13, 1918: “Persecutions of the Greeks in Turkey since the Beginning of the European War, Translated from Official Greek Documents,” by Carroll N. Brown, Ph. D. and Theodore P. Ion, D.C.L. Published for the American-Hellenic Society by the Oxford University Press American Branch, 1918:

The Hellenic populations that have been compelled to leave their homes in Thrace and Asia Minor number more than 1,500,000. With the exception of the Greek populations of Constantinople, Smyrna, and some other cities, all the Greeks of Turkey are suffering martyrdom through deportations, outrages on women, and starvation.

Half of the deported populations have perished in consequence of ill-treatment, disease, and famine. Many have committed suicide or have been massacred in the interior of Asia Minor. Those that remain are subjected to continual martyrdom as slaves or are forced to become Mohammedans. Turkish functionaries and officers declare that no Christian shall be left alive in Turkey unless he embraces Mohammedanism.

The International Association of Genocide Scholars, an organization of the world’s foremost experts on genocide, declared in 2007 that what the indigenous Greek minority of the Ottoman Empire was exposed to from 1914 to 1923 was genocide.

But persecutions of the Greeks did not cease after World War I or the founding of the Turkish republic in 1923. On September 6 and 7, 1955, Turkish mobs carried out a massive government-instigated series of attacks against the Greek-speaking Orthodox residents of Istanbul.

They destroyed and looted the homes, offices, shops, and schools belonging to Greeks as well as their places of worship. The holy images, crosses, and icons were attacked. Some of the churches were set alight and completely burned.

The mobs beat and injured many people, destroyed graveyards, exhumed the dead from their graves and dragged them in the streets.

The scope of the savagery was beyond words. In the pogrom that lasted two days, flames rose all over Istanbul from the fires that began during the plundering and destruction. The attacks greatly escalated Greek emigration from Turkey.

Today, the exact population of the Greek-speaking Orthodox citizens of Turkey is not known, as the government funded Turkish Statistical Institute (TUIK) does not conduct a census based on ethnicity — all citizens of Turkey are automatically considered ethnic Turks. But the Greek-speaking Orthodox community in Turkey is currently estimated to number less than 2000.

After 46 years, Istanbul’s Theological School of Halki is still closed.

Archbishop Iakovos of America declared the reason for his support of Rev. King in 1965:

Unlike most of you, I was not born in the United States to live and enjoy democracy. I came to the United States from Turkey where I was a third category citizen. So when Martin Luther King Jr. had his walk to the courthouse of Selma, Alabama, I decided to join him because I said this is my time to take revenge against all those who oppress people.

Upon my return, some called me a traitor; some others said I should be ashamed of what I have done. Some said that I am not an American; some said that I am not a Christian. I know that civil rights and human rights continue to be the most thorny social issue in our nation. But I will stand for both rights — civil and human — for as long as I live. I feel it is the Christian duty and the duty of a man who was born as a slave.

Under Turkish rule, Archbishop Iakovos felt like a “third category citizen,” and even a “slave” in his native land. Today, the historic school he graduated from in Turkey is not allowed to train new clergy.

By wrecking Hellenism and Greeks in Anatolia, Turkey has torn down a magnificent civilization and culture to which the world owes so much. And humanity has become devoid of the much needed wisdom and spiritual guidance of exemplary leaders such as Archbishop Iakovos.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member