When my wife and I first started dating, I worked as a retail drone at a chain bookstore. One of the things I had to do at the time was help people find books that I didn’t care for. From what I’d grown up referring to as “cheap, trashy romance novels” to political books that simply annoyed me, I helped my customers find them all and never really thought much about it. After all, I wasn’t paid for my opinions on most of those books unless a customer asked me, and then I’d reply that I hadn’t read it so I couldn’t tell them anything.

However, at least one person who is currently in that position doesn’t seem to understand this.

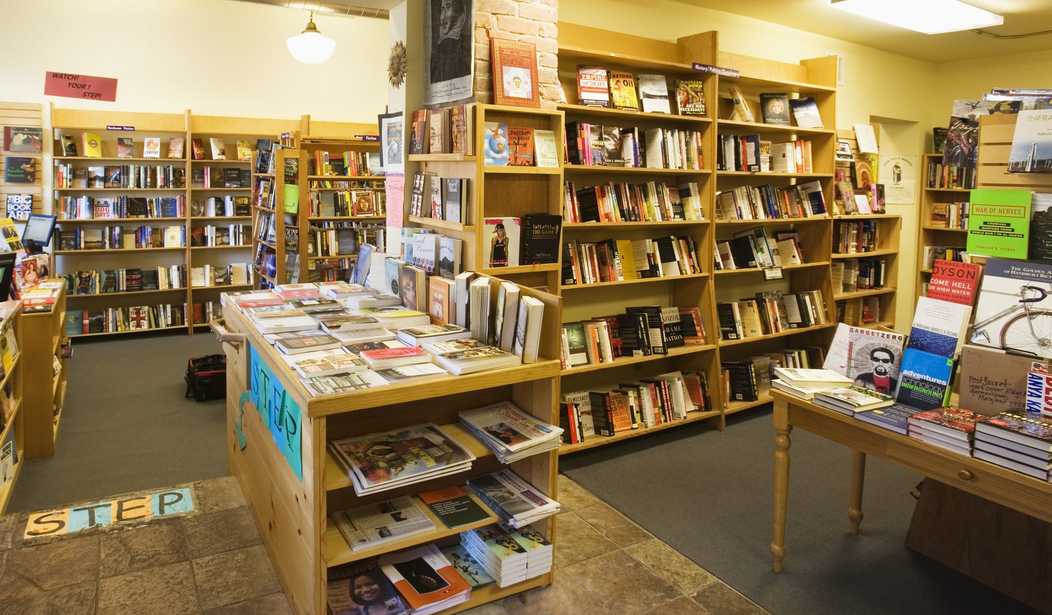

Working at an independent bookstore in the Greater Boston area, I find myself having some variation of this conversation a few times a week. To be fair, bookselling, like any retail or service job, comes with its fair share of repetitions. For example, the sales pitch for our loyalty program is so ingrained in me that it comes pouring out in a breathless flurry of words. Such things are largely innocuous, a necessary (if not occasionally tedious) part of the job. But when it comes to the above conversation concerning J.D. Vance’s bestselling memoir, there is something a bit more personal at stake, viz. my moral objection to the book that has become, for conservatives and liberals alike, a means of understanding the rise of “Trumpism.” And while it’s easy enough to take this moral high ground, it comes into direct conflict with that old chestnut about the customer always being right, to which even the most fiercely independent of bookstores largely adhere.

A moral objection to a memoir about a man working to remove himself from the poverty that plagues Appalachia? Honestly?

The author of this, Douglas Koziol, doesn’t seem to have actually read Vance’s book. Why do I say that? Well, he writes:

I don’t intend to review Elegy here. More capable pieces have already been written about the book’s “pull yourself up by the bootstraps” message, its condemnation of a supposed culture of poverty, its dismissal of the working class’s material reality as a determining factor in their lives, and its callous claim that the welfare state only reinforces a cycle of dependency. If any of this sounds familiar, it’s because these are the same rightwing talking points that have been leveled at the working class and poor for decades. As if that weren’t enough, the book also boasts glowing blurbs from the likes of Rod Dreher, whose oeuvre consists of transphobic screeds for The American Conservative; literal tech vampire Peter Thiel; and the National Review, which, under the guidance of William F. Buckley, promoted segregation and derided the Civil Rights Movement, among countless other odious stances, and which now primarily serves as a trust fund for a gaggle of #NeverTrump Republicans who hold the President’s views but gussy them up with a bowtie. And yet the customers where I work—largely liberal, well-educated and well-meaning people—have bought the book in droves.

So, he’s read a lot of people bashing the book and the wrong people seem to like it. Yet, the article in question generated a lot of discussion on Twitter, and one tweet, in particular, stood out to me. The tweeter describes herself as a progressive, yet offers this:

Furthermore, @JDVance1 never implied he bootstrapped. He repeatedly credits his grandmother, the Marines, his girlfriend for helping him.

— marymcnamara (@marymcnamara) July 19, 2017

So what happened? Koziol knew the “right” people were bashing it, so he simply assumes it was worthy of bashing.

Not only that, but he feels his sense of morality is superior to yours. After all, he offers this:

I am aware of the privilege that accompanies my fairly light moral compromise in purveying Vance’s book, but the question remains: is there any way I can use that privilege to benefit the bookstore, the customer, and myself, all at once? What have I done for the people looking for the answers Hillbilly Elegy claims to hold, and who am I to offer answers of my own?

He even goes on to “joke” that he can hide copies of Hillbilly Elegy and then he invokes the left’s favorite phrase by saying he can start a “conversation.”

Dude, you’re working retail at a book store. Your job isn’t to start a conversation with me, especially about a book that I’m buying so I can read it. No, your job is to help me find the book. Period. If I ask your opinion, then go right ahead, but otherwise, sit down and shut up. Frankly, since you consider The Bible as “insidious,” I don’t really care about your opinion in the first place.

While some bookstores have embraced an ideology, keep in mind that those that have remained open have done so in ideologically homogenous areas like Berkeley. However, they also have stayed open in spite of that embracing of ideology, not because of it. They’ve merely been so cocooned by fellow travelers that they’ve been protected from market forces that would otherwise crush a business doing so.

Most savvy business people understand that alienating potential customers is not a recipe for success, so they don’t do it — even if they’re fairly cocooned by fellow travelers themselves. After all, all it takes is one bad experience for someone to hurt a business, and lecturing customers is not a winning strategy.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member