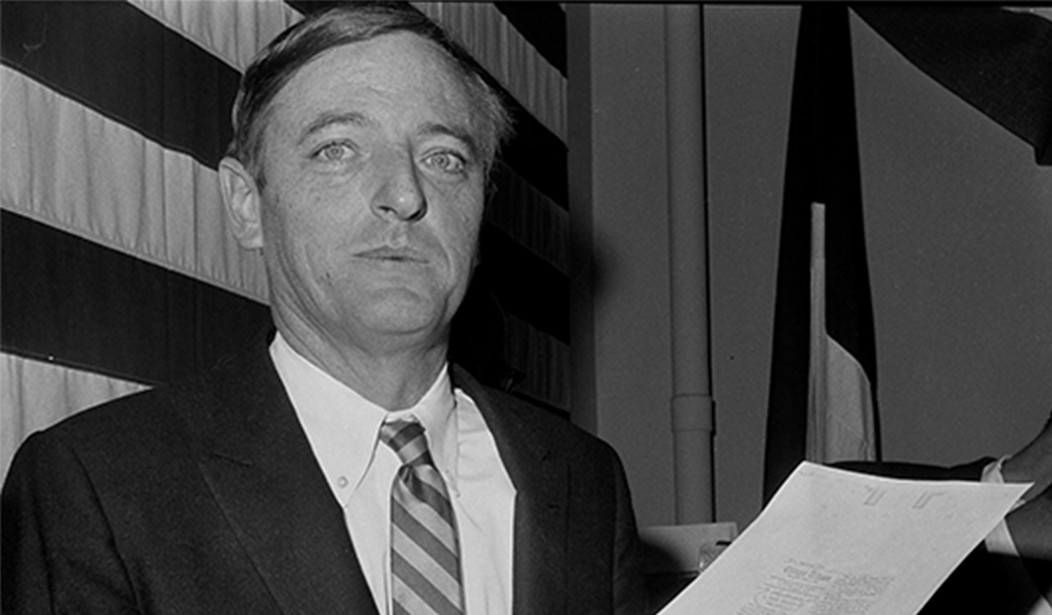

William Buckley was a force of nature. He wrote 50 books, 5,600 syndicated columns, and hundreds of editorials for National Review, the magazine he founded in 1955 when "conservatism" was barely recognized as a philosophy.

He also gave over 70 public speeches yearly and taped 1,500 episodes of his wildly entertaining TV show, "Firing Line." Sam Tanenhaus, former editor of the New York Times Book Review, spent 27 years writing the definitive Buckley biography, "Buckley: The Life and the Revolution That Changed America."

Tanenhaus has been a chronicler of intellectual conservatism for nearly 30 years. His 1997 book on Whittaker Chambers won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize and was a finalist for both the National Book Award for Nonfiction[7] and the Pulitzer Prize for Biography.

His controversial book, "The Death of Conservatism," was met with outrage on the right for its prediction that movement conservatism was on its last legs, having exhausted itself in the culture wars of the 1990s. Tanenhaus first published his ideas on conservatism's death in an essay in the New Republic, later turning the essay into a book.

After George W. Bush’s two terms, conservatives must reckon with the consequences of a presidency that failed, in large part, because of its fervent commitment to movement ideology: the aggressively unilateralist foreign policy; the blind faith in a deregulated, Wall Street-centric market; the harshly punitive “culture war” waged against liberal “elites.

The New Criterion's Roger Kimball, writing for PJ Media in 2009, said that Tanenhaus "ends by calling on conservatives to reject 'ideology' and 'recover their honorable intellectual and political tradition.'” What he means, of course, is that conservatives should stop being conservatives and get with the leftoid program as epitomized by the geist of The New York Times and Barack Obama.

Indeed, Tanenhuas was glimpsing the stirrings of a new kind of conservatism. Partly cultural, partly ideological, its primary tenet was that intellectual conservatism is a bust and must be supplanted by something more populist.

In 2016, one of those intellectual conservatives, Yuval Levin, praised Tanenhaus for believing that Donald Trump was on to something. "He understands well that Trump has tapped into legitimate concerns about trade, downward social mobility, and diminished opportunity,” Levin wrote. As it was, with Trump's election, the intellectual right was either sidelined or left the party.

Buckley changed the 20th century. Will Trump change the 21st? William Voegeli of the Manhattan Instituti criticizes Tanenhaus's shortchanging of Trump. "Buckley" fails to explore what Buckleyism and Trumpism might reveal about each other.

This approach might have worked had Trump lost the 2024 election, which took place as Tanenhaus and his publisher were putting the final touches on the book. In that case, one could argue that 2016 was indeed an earthquake—but also an anomaly, a moment whose sound and fury signified nothing of lasting import. The assumption that Buckley would be remembered long after Trump was forgotten might, under those circumstances, justify telling Buckley’s story without reference to the 45th president. But that premise collapsed the moment Trump crossed the electoral threshold to become the 47th president. After 2024, the relationship between Buckleyism and Trumpism is not only hotly debated; it is also central to understanding the nature and direction of the conservative movement, Buckley’s legacy.

Is Buckley's influence eradicated in the age of Trump? The way that Buckley used to toy with his liberal guests on "Firing Line"—grinning like the Cheshire cat, setting up his left-wing duck, and then knocking him down with devastating exactness, softened by a touch of humor—was unforgettable. The weekend before "Buckley" was published, Tanenhaus wrote “The Cerebral, Bach-Loving Patrician Who Wrote Trump’s Playbook" as an essay in the New York Times. It's the only mention of Trump relating to "Buckley" that Tanenhaus saw fit to make.

I don't know what Bill Buckley would have made of Donald Trump, the candidate or the president. I believe he would have appreciated his political instincts and his ability to hit the bullseye when savaging an opponent. But the reality is that Trump is not only the opposite of Buckley in temperment and personality. I don't think Bill Buckley would recognize Trump's agenda as being "conservative."

In that respect, Trump's connection to Buckley is tenuous at best.