Conducting an election where 50 percent or more of the ballots are mailed in will be a nightmare for voters and election officials. This is the lesson we learned from the spring and summer primaries where some states took weeks to declare all the winners.

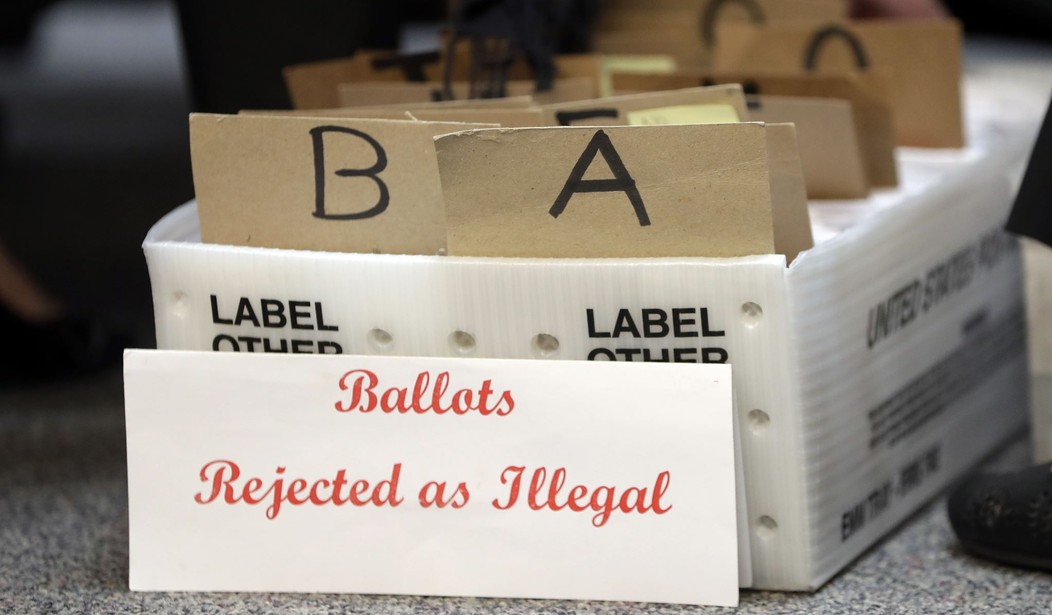

One of the major hold-ups was the staggering number of rejected absentee ballots. The fact is, this will be the first election most voters will be mailing in their ballot. There are proper procedures to follow or your ballot will be tossed. People being people, tens of thousands of voters will mail in their ballots late, or fail to sign their ballots, or even fail to fill them out. Other ballots will be disqualified because the voter signature on the ballot does not match the one on file.

We’ve been hearing the warnings from election officials about the chaos that will reign after the presidential election. The AP did a study of what that might mean for the count.

The sudden leap is worrisome: 22 states are going from absentee ballots comprising less than 10% of all ballots four years ago to perhaps half or more this November. Pennsylvania is among them: Nearly 51% of all votes cast during its June primary were mail-in.

If voter turnout is the same as 2016 and the ballot rejection rate equals the 1.4% from this year’s primary, nearly 43,000 voters in Pennsylvania could be disenfranchised this fall, according to AP’s analysis. That’s almost the same number of votes by which Trump defeated Democrat Hillary Clinton in the state four years ago, when some 2,100 ballots were rejected.

In closely fought battleground states, court challenges of rejected ballots and appeals of those decisions to the courts could last into next year. It’s a distinct possibility that several states will be close enough that the rejected ballots could spell the difference between victory or defeat for either candidate.

Suppose a judge rules that late ballots can be accepted because the postal service is slow? Or that signatures matching shouldn’t matter?

It’s going to get very, very messy.

For its analysis, the AP also collected absentee ballot data from Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin. Based on the percentage of those ballots cast in each state’s primary this year, between 185,000 and 292,000 voters in the seven states examined could be disenfranchised if November’s turnout matches that of four years ago and the rejection rate remains flat. That compares to nearly 87,000 ballots rejected in those states in 2016.

The ballot rejections could be pivotal in close races. In 2016, Trump won Wisconsin by roughly 23,000 votes

It’s very likely that the race will hinge on which rejected absentee ballots are accepted and which remain rejected. That’s an entirely unacceptable state of affairs that was never necessary to begin with.

When the mail-in ballot proposals were first passed in state legislatures, we didn’t know much about the coronavirus, how easy it was to spread, how sick people got, how to protect vulnerable populations. It appears that as many as 71 people contracted the coronavirus while voting in Wisconsin — out of more than half a million votes cast in person. That infinitesimally small number of infections should have been a signal to the rest of the country that it was relatively safe to hold an in-person election.

Instead, the push to force voters to mail in their ballots intensified. It was justified by the pandemic — as everything else in these times. We can speculate about the reason why, but if it’s hardly more dangerous to go in person to cast your ballot, we might ask which party gets an advantage from mail-in voting. We’re assured that neither party benefits, but in a close election, that simply isn’t true. Democrats have been pushing mail-in voting with their constituencies, leading to far more mail-in ballots cast by Democrats than Republicans.

That may change on Election Day. But for now, you have to clearly give the advantage to the left.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member