On Tuesday, the U.S. Supreme Court officially struck down one of the worst rulings in its history after 74 years. In Trump v. Hawaii, Chief Justice John Roberts officially condemned Japanese internment and the Court case upholding the racist practice, Korematsu v. United States (1944).

While Trump v. Hawaii focused on President Donald Trump’s temporary travel ban regarding countries of terror concern — often attacked as a “Muslim ban” — an argument against the travel ban gave the Supreme Court a rare opportunity to reverse one of its most notorious rulings.

“The dissent invokes Korematsu v. United States,” Roberts noted. “Whatever rhetorical advantage the dissent may see in doing so, Korematsu has nothing to do with this case.” Even so, he took the opportunity to reverse the notoriously racist ruling.

“The forcible relocation of U. S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of Presidential authority,” the chief justice declared. “But it is wholly inapt to liken that morally repugnant order to a facially neutral policy denying certain foreign nationals the privilege of admission,” i.e. the Trump travel ban.

Roberts (and the four other conservative members of the Court) upheld Trump’s action because it was “facially neutral” and tailored to national security, not racial or religious animus.

“The dissent’s reference to Korematsu, however, affords this Court the opportunity to make express what is already obvious: Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—’has no place in law under the Constitution,'” Roberts declared.

The Court decided Korematsu in the context of the war with Japan (1941-1945). Although the American population originally stood with the large population of Americans of Japanese descent in the West, U.S. military authorities warned that these descendants would pose a security risk.

In February 1942, FDR signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the forced removal and internment of Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Shortly before this action, a few Japanese Americans in Hawaii had attempted to help a Japanese pilot escape, spurring fears of Japanese disloyalty in America.

The order was arguably racially motivated, however, since those with as little as 1/16 Japanese descent could be placed in the camps. Major Karl Bendetsen said in 1942, “I am determined that if they have one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must go to camp.”

More than 110,000 Japanese Americans on the mainland U.S. were forced into camps. In Hawaii, where more than 150,000 Japanese Americans made up over one-third of the population, only 1,200 to 1,800 were interned.

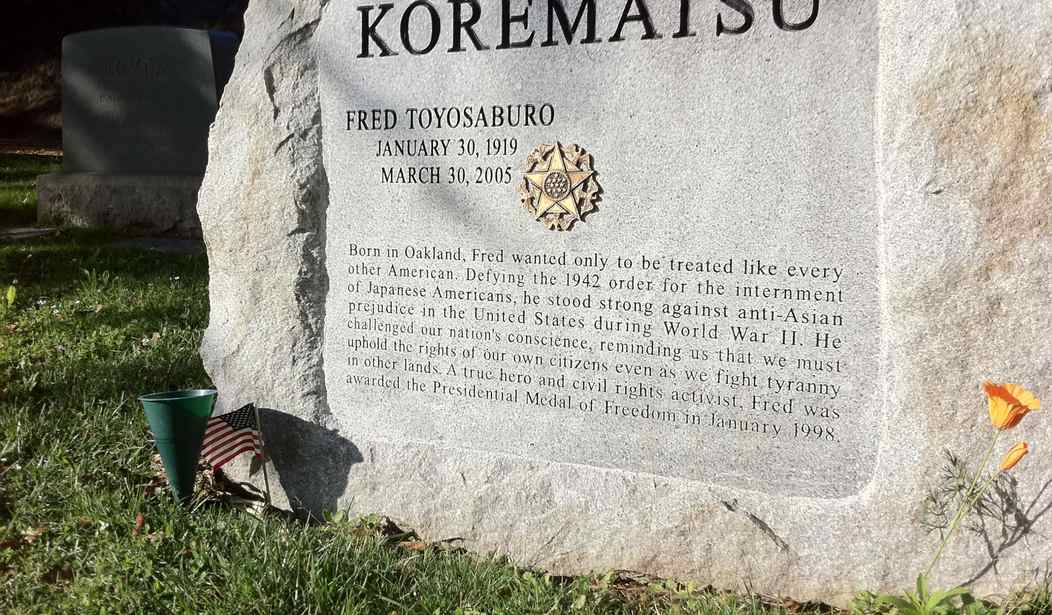

Fred Korematsu, a Japanese American in San Leandro, Calif., violated the order, and even went so far as to have plastic surgery to conceal his identity and avoid the internment camps. The Supreme Court upheld his conviction (6-3), with Justice Hugo Black defending the internment camps as an essential national security measure.

In 1980, President Jimmy Carter opened an investigation to determine whether Japanese internment had been justified. The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Citizens (CWRIC) found little evidence of Japanese disloyalty at the time and concluded that racism, rather than national security, lay behind the policy.

Racism against Japanese Americans flared up in the early decades of the twentieth century, with groups such as the Asiatic Exclusion League, the California Joint Immigration Committee, and the Native Sons of the Golden West teaming up to oppose this “Yellow Peril.” The Immigration Act of 1924 extended the anti-Asian exclusion of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act to the Japanese population.

Due to these and other findings, the CWRIC recommended that the government pay reparations to the internees. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which apologized for the internment and authorized the payment of $20,000 ($41,000 in 2017 dollars) to each survivor.

The legislation admitted that government actions were based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” The government gave out more than $1.6 billion in reparations to 82,219 Japanese Americans who had been interned and their heirs.

Roberts’ decision to overturn Korematsu in this case is both admirable and long overdue.

National Review‘s Dan McLaughlin suggested that Roberts’ “theatrical overruling of Korematsu may be a shot across the bow, reminding Trump that his power to exclude people from the country is not so broad when it comes to those already here.”

And the theatrical overruling of Korematsu may be a shot across the bow, reminding Trump that his power to exclude people from the country is not so broad when it comes to those already here.

— Dan McLaughlin (@baseballcrank) June 26, 2018

Whether or not the chief justice meant it in this way, the overturning of Korematsu is a clear and overdue moral victory, and even liberals who lament Trump’s lawful travel ban should be able to celebrate this aspect of Trump v. Hawaii.

Ironically, Rep. Keith Ellison (D-Minn.) has already attacked the ruling as a “marker of shame,” comparing the defense of Trump’s travel ban to Plessy v. Ferguson, an 1896 Supreme Court case upholding the constitutionality of race-based segregation. At least when it comes to Korematsu, he couldn’t be more wrong…

Join the conversation as a VIP Member