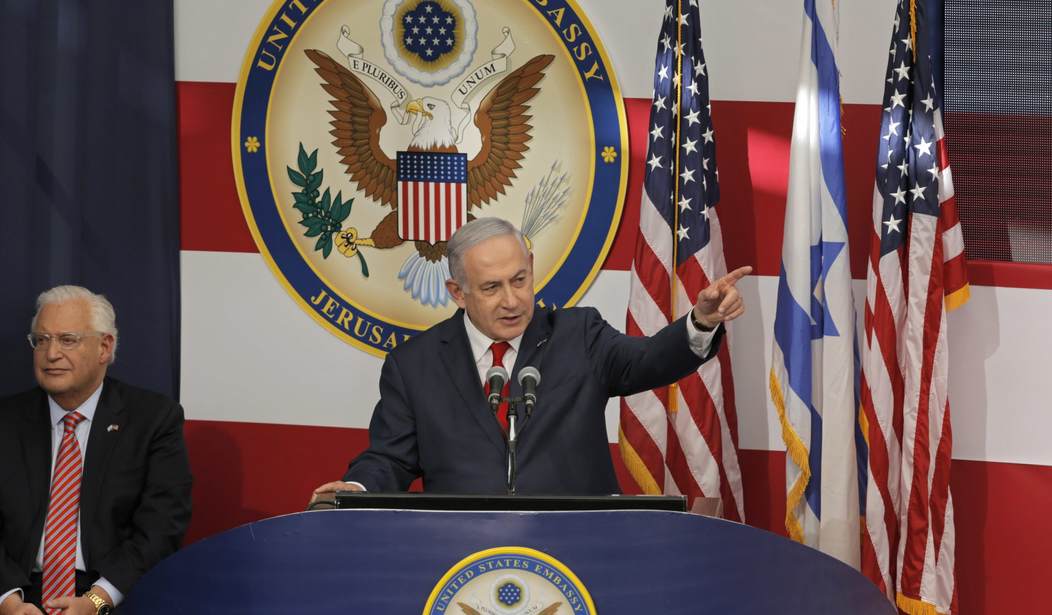

France shunned the inauguration ceremony of the United States Embassy in Jerusalem on

May 14. So did most other European Union countries, with the remarkable exception of Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Romania. The Czechs, the Hungarians and the Romanians went so far as to block, on May 11, a newly drafted EU statement reiterating the Union’s condemnation of the American embassy transfer.

The French and mainstream European stand runs against plain logic. Both France and the EU claim that the 1949-1967 ceasefire lines between Israel and Jordan in the Jerusalem area (the “green line”) are an international border. If this were indeed the case, those sectors in Jerusalem held by Israel during this period of time (“West Jerusalem”) would be internationally recognized Israeli territory. Accordingly, Israel would have every right to turn them into its capital, and the United States, or any other country, to locate its embassy there.

Likewise, France and the EU countries recognize Jerusalem as Israel’s de facto capital, since they routinely visit the Israeli government or the Israeli parliament there. Under international law, a de facto recognition is as valid as a de jure recognition.

Why then should France and the mainstream EU oppose the transfer of the American embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem (or at least to “West Jerusalem,” where the new premises are located) and boycott the inauguration ceremony?

They opine that such a transfer is still a violation of “international law,” inasmuch as it departs from an aggregative corpus of United Nations General Assembly and Security Council resolutions. In particular, Paris and Brussels point to Security Council Resolution 470, passed on August 20, 1980, which condemned the enactment by Israel’s parliament of a constitutionally binding law enshrining Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, and called on the governments that had already established embassies in that city to withdraw them. Resolution 470 was largely based on the previous Security Council’s Resolution 252 of May 21, 1968, which in turn was based on the General Assembly’s Resolution 303 (IV) of December 9, 1949.

Are France and the mainstream EU correct? Are these resolutions in particular, and other United Nations resolutions in general, coextensive with international law?

Hardly.

First, it should be emphasized that the United Nations is not a confederacy of sorts or a super-government, whose decisions would be binding on the member States. The UN is a free association of sovereign countries which ultimately remain free to abide by them or to ignore them. The assertion that the United Nations Charter is a “constituent treaty” and overrides national laws and prerogatives is unfounded.

Article 103 of the Charter, which is casually mentioned in this respect, says that in the case where a member State’s obligations under the Charter would contradict other obligations under a State-to-State treaty, the former would prevail over the latter. Accordingly, the UN has no capacity to decide the exact location of Israel’s capital, nor to condemn those countries that happen to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

Second, it should be stressed that United Nations resolutions carry very little authority — according to the Charter itself.

The General Assembly’s decisions carry no authority at all: they just warrant some kind of consensus between the UN’s members, as the 19th century “Concert of Europe” used to do.

The Security Council essentially revolves around the Five Permanent Members, or Great Powers — that is to say the five largest military powers in the world. Its resolutions carry authority only in the very rare instances where the Great Powers agree to implement them together; that is to say, again, to use their superior military forces to that effect together, or to allow one of them to use its individual military forces on their common behalf. It is well known that every individual Great Power may therefore veto a Security Council resolution.

What is not well understood is that, unlike formal treaties between sovereign countries, Security Council resolutions lapse at the very moment one of the Great Powers decides not to abide by them. Which is precisely the case regarding the United States government’s decision to disregard Resolution 470.

Third, one should remember that the United Nations was originally intended as an improved, healthier version of the previous international body, the League of Nations. In particular, it was not to be rooted on principles only and on the fallacy of a complete equality between the member States — as was the League of Nations — but in the realities of world politics and the balance of powers: hence the special role assigned to the Great Powers. However, the admission into the UN of growing numbers of weak, immature or non-functional polities, usually as part of the decolonization process, or even the retention of failed and no longer existing polities (from Somalia to Syria), largely reversed or annulled these realistic provisions and allowed for growing numbers of unrealistic resolutions to be voted.

The more divorced from realities they are, the less United Nations resolutions are valid according to the spirit, logic, and letter of the United Nations Charter. And according to international law.

General Assembly Resolution 303 (IV) of 1949 was a very early instance of divorce between UN resolutions and realities. It maintained that the Corpus Separatum provisions in the Jerusalem area, as outlined by the 1947 partition plan of Palestine, were still valid, notwithstanding that: this plan had never been implemented; that all its provisions were accordingly null and void; and that a completely different situation had arisen on the ground following Israel’s Independence War and the Rhodes Israeli-Jordanian ceasefire. Security Council Resolution 252 of 1968 blindly referred to the illusional Resolution 303 (IV), and in addition ignored the new situation created by the Six Days War and a further Israeli-Jordanian cease-fire. Security Council Resolution 470 of 1980 no less blindly built up on both Resolutions 303 (IV) and 252. None of these resolutions should be seen as pertinent.

There is an even more definite argument against the French and European reliance on UN resolutions on Jerusalem: the fact that France superbly ignored other UN resolutions directed at her.

The case story is Mayotte, a tiny island in the Indian Ocean halfway between Mozambique and Madagascar. In geographical, anthropological and cultural terms, it belongs to the volcanic Comoros Archipelago, which was settled in turn by Polynesian, Melanesian, Malay, African, Arab, Persian and South Asian sailors, traders and slaves, and converted to Islam in the 16th century. A French dependency from 1841 on, the Comoros were granted independence in the early 1970s as a single Islamic Republic.

Mayotte, however, unanimously insisted in two successive referenda, in 1974 and 1976, to stay French. Paris grudgingly acquiesced, at least as a temporary solution. Finally, a third referendum, in 2009, confirmed the local population’s wishes: in 2011, Mayotte was reorganized as the 101st full-fledged French département, or county. In spite of the distance, it is as French as Hawaii and Alaska are American. By the same token, it was recognized in 2014 as an integral part of the European Union.

The Republic of the Comoros rejected Mayotte’s “secession” and its “continuing occupation” by France. This was a consistent move within the context of the “decolonization process,” as defined by General Assembly Resolution 1514 (XV) of December 14, 1960, and by General Assembly Resolution 2621 (XXV) of October 12, 1970.

The issue was deferred to the Security Council, which overwhelmingly voted on February 6, 1976, for Mayotte to be “returned” to the Comoros, by 11 votes against 3 abstentions (the United States, the United Kingdom and Italy). For the first time ever, the French resorted to their veto powers as a Security Council Permanent Member — and blocked the draft.

However, France could not prevent the General Assembly from passing a similarly worded resolution a few days later, nor from voting again every year until 1995 on the “Question of the Comorian Island of Mayotte.” While no further resolution has been voted since 1996 (after all, France is very big, and the Comoros are very small), the previous resolutions are still in force — as the Comoros have not failed to recall to this very day.

Admittedly, there might be more to be said for the continuation of French rule in Mayotte than for the implementation of “decolonization” there. And the French may be right, in many ways, to ignore the United Nations resolutions pertaining to this Indian Ocean island.

However, what the French cannot possibly do is scold Israel — or the United States — for not abiding by absurd United Nations resolutions while acting exactly like Israel or the United States when it comes to Mayotte.

In other words, they cannot found their foreign policies on double standards. Nor can the European Union.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member