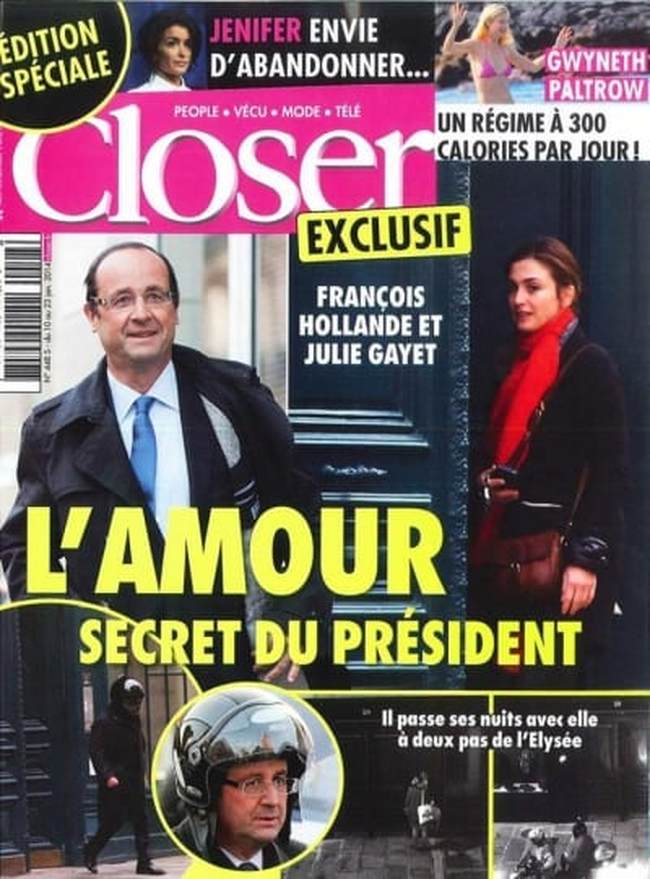

Truth be told, despite the best efforts by the French and British media to sell their wares, one can hardly call it Gayetgate. Indeed, the president of France, François Hollande, 60, has a mistress, actress Julie Gayet, now 41, whom he met about two years ago, even before being elected. Two weeks ago, Closer, a gossip weekly, published a seven-page report that included pictures of the president paying a visit to Gayet’s love nest, an apartment located on Rue du Cirque, one block away from Elysée Palace, the French head of state’s residence in central Paris. However, 77% of the French see it as a private matter. In other words, they do not care.

Nobody is calling for the president to resign, or apologize, or engage in explanations — even if he appears to be betraying Valerie Trierweiler, 49, the partner who lives with him at Elysée and enjoys — at least for the moment — a de facto first lady status. The main political repercussion is that the Gayet case eclipsed Hollande’s January 14 press conference, a very important event where he admitted that his socialist policies — choking taxation (especially for entrepreneurs and the middle class) and welfare benefits for growing numbers of “underprivileged” citizens and residents — were a failure. At the same press conference, Hollande promised to turn to a more pro-business agenda.

One reason for such leniency towards Hollande in the Gayet case is good old Gallic tradition. In France, as in many European countries, kings or presidents have always kept mistresses quite casually. Every French king or emperor was reported to entertain one or several “favorites,” except the devout Louis IX (1214-1270), whom the Catholic Church canonized as Saint Louis; and the reform-minded Louis XVI (1754-1793), who inadvertently ushered in what was to become the Great French Revolution in 1789 — and lost both his throne and his head in the process.

Then-President Nicolas Sarkozy of France and his wife Carla Bruni-Sarkozy attend the laying of a wreath at the statue Of Charles De Gaulle on March 27, 2008, in London, England. Photo by Entertainment Press / Shutterstock.com.

In more recent times, presidents were not much different than their royal predecessors. Felix Faure famously passed away at Elysée Palace’s Salon Bleu in 1899 while allegedly being “serviced” by Mrs. Marguerite Steinheil. François Mitterrand — president from 1981 to 1995 – was dubbed “Francois the Seducer” and kept a second family on state-owned and state-funded premises. Jacques Chirac, who succeeded him, enjoyed many passing or lasting relationships. As for Nicolas Sarkozy, president from 2007 to 2012, he divorced twice before settling with former top model Carla Bruni, whom he dutifully married in 2008.

Another reason for French leniency is that Hollande is a decidedly non-marriage-oriented man. He lived for twenty years with Segolene Royal, now 60, a strong-headed political woman who was the unsuccessful socialist candidate for president in 2007, and had four children with her, without being married to her. Likewise, neither did he marry Valérie Trierweiler, a twice-divorced journalist, nor even engage in looser a civil partnership with her (PACS in French legal terminology). He was, at most, rude or discourteous towards Trierweiler; but he did not cheat on her technically.

The Lessening of French Mores

But a deeper reason is that Hollande’s case actually reflects the present state of French mores. The marriage rate in France dropped from 7.8 per 1000 in 1970 to 3.7 per 1000 in 2011: as a matter of comparison, it still was 6.8 in the United States in 2013. The divorce rate in France soared from 0.8 per 1000 in 1970 to 2 per 1000 in 2011. Laws and codes were streamlined in order to erase any differences between married and unmarried couples, legitimate and illegitimate children, and man/woman and same-sex partnerships. Religious marriage declined dramatically, especially among Catholics: barely one French couple out of four currently gets married in a church. One French family out of five is a single-parent family. One family out of ten is a recomposée (reconstructed) family where children born out of previous marriages or partnerships are raised together. A further indication of the decline of marriage as a social pattern is that 53% of the French think that one can be unfaithful and still be in love, while 58% think they can forgive their partner’s unfaithfulness.

Within such a context, Hollande’s vaudeville-esque behavior may almost appear acceptable. What still may be questioned is the need for an unmarried president to keep an unmarried first lady, or whether his security as the head of the country (and the holder of France’s nuclear strike codes) can still be ensured while he wanders at night, even for such short drives like the Rue du Cirque.

Julie Gayet at the gala premiere for Blood Ties at the 66th Festival de Cannes. May 20, 2013 Cannes, France. Photo by Featureflash / Shutterstock.com.

The French tend to glorify their open-mindedness in these matters and flatter themselves by comparing their values to French perceptions of those “puritanical” Americans who still pay so much attention to traditional marriage and traditional family values. And while they may be dead wrong — one should not make too much out of historic parallels – it’s worth considering some earlier precedents.

Take Old Rome, for Instance

Roman marriage was originally a religious ceremony known as confarreatio — just as until very recently religious marriage was an essential part of French family life. A Roman marriage took place in front of priests and ten witnesses. Husbands were supposed to enjoy full authority (manus) over their wives, but abuse of power — like selling one’s wife into slavery or prostitution — was deemed to be criminal. Divorce procedures were lengthy and costly; some husbands could be requested to give away half their assets and money to their repudiated spouse.

Over the years, an alternative marriage known as coemptio was devised: husbands bought their wives for a copper coin in front of five witnesses. From the Romans’ perspective, this was a purely civilian ceremony, and was performed without priests — a fact that allowed for the wife’s almost complete emancipation in most private and financial matters. But even that proved too much: common-law marriage, usus, eventually prevailed. Spouses were now free partners living together for their mutual benefit and entitled to separate at will.

The rationale behind the gradual loosening of Roman marriage was concern about the low birthrate and depopulation — the unintended and inevitable consequence of greed and hedonism among the elite and large-scale slavery. Religious or even full-fledged civilian marriage was burdensome; moreover they could not take place between aristocrats and plebeians, or between free men and slaves. Usus, however, was feasible whatever the circumstances. From Augustus on, it was increasingly backed by government and law. In contemporary France, Hollande-style informal partnerships have gradually become the norm and even the legal norm for similar reasons: in order to reconcile sexual freedom and chaotic social or economic conditions with the need to produce at least a few children.

Roman usus was of little help. Depopulation went on, compounded by pandemics and other health disasters. The Roman Empire turned to a last option: to let foreign nations in as auxiliaries of all sorts. The Arabization of the eastern parts of the Roman Empire was already a fact in the third century, more than three centuries before the rise of Islam: Queen Zenobia of Palmyra (Zainab in Arabic), a Romanized Arab ruler, almost carved for herself in 271 BC a new empire encompassing Eastern Anatolia, the Levant and Egypt. The Germanization of the Roman West started at about the same time and was completed during the fifth century, when barbarian kingdoms substituted for a collapsing Western Roman Empire.

Likewise, the decline of marriage and family in contemporary France (and most other European country) is evidently linked to an ever growing immigration from non-European countries, including staunchly Islamic Arab and African countries.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member