On my last trip to Iraq, I asked a number of Americans and Iraqis what they think about the future in that country. Around half were optimistic and half were pessimistic. This is the third installment in a four-part series. Optimists were quoted at length in parts “one”:http://www.michaeltotten.com/archives/2009/05/the-future-of-i.php and “two”:http://www.michaeltotten.com/archives/2009/05/the-future-of-i-1.php. I’m giving equal time here to the pessimists.

The United States has basically won the war in Iraq. No insurgent or terrorist group can declare victory or claim Americans are evacuating Iraq’s cities because they were beaten. America’s most modest foreign policy objectives there have been largely secured. Saddam Hussein’s toxic regime has been replaced with a more or less consensual government. I doubt very much that Iraq will seriously threaten the United States or its neighbors any time soon. It isn’t likely to be ruled by terrorists as it probably would have been if the United States left between 2004 and 2007. It’s a relief. A few years ago, I was all but certain the U.S. would withdraw under fire and leave Iraq in the hands of militias. Even so, many have a hard time feeling optimistic about the future. Iraq remains, in some ways, a threat to itself.

The reduction in violence and the winding down of the conflict allowed me to see the country a little more clearly than I could when I first visited Baghdad. I’m sorry to report that the city is still as run-down and dysfunctional as it was when what passed for daily life was punctuated by gunfire and car bombs. Iraq is backward and messy not only by Western standards, but by Arabic standards.

“A lot of people want us to stay or they will leave,” U.S. Army Sergeant Nick Franklin told me. “They don’t care where they go. They want to go to America, to Europe, or even to Jordan or some other Arab country. They don’t care. They just want out.”

You might want out, too, if you lived there. Violence has been drastically reduced, but sectarian tension remains just as bad, if not worse, as it is in Lebanon — and the possibility of renewed civil strife hangs over Lebanon like the Sword of Damocles. Iraq is still violent compared with most countries, and the entire government and security forces are shot through with corruption. Electricity still doesn’t work half the time. Sewage still runs in the streets. Neighborhoods are still clotted with an appalling amount of garbage. Police officers steal from citizens and often beat suspects up not during but before interrogations.

I asked several American soldiers if it was safe enough for me to walk the streets on my own without armed protection. Few thought that would be wise.

“I wouldn’t try it,” Sergeant Manuel Juarez said. “I wouldn’t even think of it. Who is to say that these Sons of Iraq guys don’t still have some ties to Al Qaeda? Once in a while we get reports about one of them being shady.”

Sergeant Manuel Juarez

The Sons of Iraq work for the Iraqi government as low level security officers, basically as neighborhood watchmen.

“Sons of Iraq is shady as hell,” said another soldier who overheard our conversation and preferred not to be named. “I know as a fact that they’re shady as hell.”

“What do you know?” I said.

“I don’t know anything,” he said and looked away. That was all he would tell me.

An armed Sons of Iraq member, Adhamiyah, Baghdad

We were in Adhamiyah, a mostly Sunni area north of the city center and east of the Tigris. It was a stronghold of support for Saddam Hussein’s regime, and a stronghold of support for Al Qaeda more recently. American infantry soldiers at Forward Operating Base (FOB) Apache, next to the famous “Gunner Palace”:http://www.gunnerpalace.com/, hosted me during my stay.

Staff Sergeant Christianson said he didn’t think I would be much safer when I later moved into the Shia parts of the city even though the Shias, overall, are friendlier toward Americans.

“Hezbollah kills civilians as well as Americans with total disregard for Iraqis,” he said.

He was referring, of course, to Hezbollah in Iraq, not to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps, though, is a patron and armorer of both. A crucial difference between the two is that the Iraqi branch of Hezbollah, unlike the Lebanese branch, doesn’t have anything that looks even vaguely like a “political wing.” Its members don’t build hospitals, schools, or anything else. They just kill people.

Hezbollah in Iraq logo

Hezbollah in Lebanon flag

“Jaysh al Mahdi is much more careful and only tries to kill us,” Staff Sergeant Christianson continued. “I don’t know why Hezbollah is so much more ruthless, but they are. When we pull out of this country, this place is going to burn.”

No one can know if it really will burn. Many think it will, but not everyone does. Certainly nobody I spoke to hopes that it does. Even the relative optimists, though, are concerned that it might.

“I sure hope this holds,” Sergeant Pennartz said, “because we’re going to pull out soon. I think it’s a mistake. This country is going to need help for years. But at the same time I really really really don’t want to come back here. That’s how a lot of us feel. We don’t want to pull out, but we also don’t want to be here. I just hope the peace holds so we don’t have to come back and fight for the ground we already won and abandoned. Again.”

An American Humvee, Adhamiyah, Baghdad

American soldiers have since withdrawn from most of Iraq’s urban areas. We’ll have a better idea soon enough whether the optimists or the pessimists turn out to be right.

“On the surface everyone will tell you Sunnis, Shias, we don’t care, we’re all Iraqis,” Sergeant Pennartz continued. “But talk to them for a while and they’ll tell you what they really think. Do you know what those Shias did? Et cetera. Some Sunnis say Shias were never in Iraq until the Iran-Iraq war. Some are totally ignorant and say they’ll never live next to Shias. It’s worse among the older generations, like back in the States.”

I joined Lieutenant Eric Kuylman and his men on a foot patrol in Adhamiyah. Our convoy of Humvees parked near a traffic circle and we stepped out to talk to people who lived in the neighborhood.

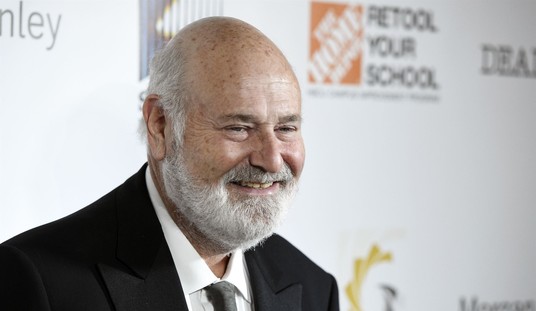

Lieutenant Eric Kuylman

The lieutenant approached a group of young men and asked if they lived in the area.

“I’m from Fallujah,” said the first in good English. “I go to college here and commute three hours each day.”

“It takes three hours to get here from Fallujah?” I said. If Iraq were a normal country, it would only take an hour or so to drive in from there.

Lieutenant Eric Kuylman (left) speaks to Iraqi college students

“The security checkpoints slow us down,” he said.

“Okay,” Lieutenant Kuylman said. “You guys aren’t from around here. I’m curious, then, what you think of the area.”

“The security is good,” the man said. “I had to quit college in 2006 because it was too dangerous. But I was able to come back this year because it’s safer. I’d like to see American forces here as guests, not carrying weapons or wearing armor.”

“Me, too,” Lieutenant Kuylman said and laughed. He wasn’t indulging the man. He was serious.

“I hope you can leave Iraq soon,” the man said.

“Me, too,” said the lieutenant.

We moved on and I asked our interpreter Tom what the Iraqis in Adhamiyah really think of the American military. He’s an Iraqi who grew up in Baghdad. “Tom” is the nickname he uses to conceal his identity.

“Eighty percent in this area don’t like Americans,” he said. “Some want American forces to stay, but most want them to leave.”

“How would you characterize their negative feelings?” I said. “Irritation? Hatred?”

“Both,” he said. “It depends. You have to understand that this was a favored area when Saddam Hussein was the president. It was a Baath Party stronghold.”

Adhamiyah, Baghdad

“Do they credit Americans with improving security?” I said.

“Yes,” he said. “But they still want American forces to leave. You heard what that guy just said.”

The Sunnis of Adhamiyah have rational reasons to dislike Americans. Sunni Arabs make up only 15-20 percent of Iraq’s population, but they were favored under Saddam Hussein’s regime. Iraq’s democratic elections have empowered the country’s Shia majority — an ancient foe of the Sunnis — for the first time.

Rational anti-Americanism, however, is compounded by the conspiratorial and phantasmagoric anti-Americanism that persists in much of the Arab world. One of Iraq’s various insurgent groups recently tried to fire an improvised IRAM rocket at a joint American-Iraqi security station, but the trigger man botched the job and blew up the rocket on the launch pad. He killed himself and destroyed nearby houses. Most residents of the neighborhood think American soldiers dropped a bomb from a helicopter.

Blackhawk over Adhamiyah, Baghdad

An Iraqi man walked up to Lieutenant Kuylman and me. His friends followed.

“I want to say something,” he said in English. “Please don’t hand us over to the Iraqi Army. We’ve been working with you for over a year.”

He belonged to the Sons of Iraq program and was worried about what might happen to him if he had to rely on the Iraqi Army for protection from terrorists instead of the United States Army.

Lieutenant Kuylman and Sons of Iraq member

“Look,” Lieutenant Kuylman said. “We’re not running away. We aren’t just going to abandon you.”

It’s true that the Americans aren’t running out of Iraq. But they did recently withdraw from the cities and will no longer be available to provide security as they did during and after the surge. Everyone in Iraq knew this was going to happen when I was there and recorded this exchange.

Lieutenant Eric Kuylman speaks to members of Sons of Iraq

From the look on the Iraqi man’s face, he was not at all convinced by what Lieutenant Kuylman said. He probably doesn’t know what happened to the anti-Hezbollah South Lebanon Army in 2000 when Israel withdrew its armed forces from Lebanon, but he was clearly worried he and his men might suffer a similar fate. Many South Lebanon Army soldiers ended up in Israel as refugees when Hezbollah took over the area.

*

Sergeant Nick Franklin took me with him when he visited the home of an Iraqi woman named Malath who is in charge of a Sons of Iraq search unit. She invited us to sit on couches in her living room. Incense wafted in from the kitchen. It smelled lovely, unlike Baghdad outside which often smells of rotting vegetables, diesel fuel, and piss.

“This is your house,” Malath said.

“If this is my house,” Sergeant Franklin said, “where’s my room?”

Everyone laughed.

Her house was much nicer inside than FOB Apache, where Franklin lived and where I was sleeping. Her living room was cozy. Peach-colored lights cast a soft glow on the wall. Arabic music videos from Egypt and Lebanon played on the television.

Malath’s living room

“You could even put me on the roof,” Sergeant Franklin said.

The roof would be more comfortable than the cramped conditions back at the FOB. Living conditions for American soldiers in Iraq are terrible. Unlike Iraqis, they get 24 hours of electricity every day, which means they have air conditioning. But every Iraqi house I have ever been in is vastly more comfortable over all.

Malath and Sermad

Malath’s colleague Sermad Mahmoud sat next to her on the couch. Sergeant Franklin sat next to me on the other side of the room.

“Malath’s family is liberated,” he said, which meant no male family members imposed a strict code of behavior on her. “She’s not married, but she helps take care of her family’s kids. Her brother was recently killed. Somebody poisoned him.”

“How’s things in Adhamiyah lately?” he said to Malath.

“Quiet,” she said.

And it was. The only gunshots I heard were fired by Iraqi Police officers into the air.

A young boy, presumably Malath’s nephew, brought us glasses of tea, fruit juice, and cigarettes.

Franklin and Malath engaged in idle chitchat for a while. Socializing often makes up the bulk of meeting time when Americans and Iraqis get together to talk business. Iraqis prefer it that way, and Americans yield to their expectations and culture.

I was given a bit of time to talk to Malath myself.

“How have things changed in the past year?” I asked her.

“Al Qaeda controlled this entire area in 2007,” she said. “The market had to close at 4:00 pm. They came in from other provinces in Iraq. The strangers came from places like Abu Ghraib and Fallujah. When Americans created Sons of Iraq, we cooperated because we know the locals. We know who is supposed to be here and who is from outside. We helped them raid the bad houses. It started to get better here in November of 2007 when Sons of Iraq started. We used to find dead bodies in the streets every day in this neighborhood, but not anymore. They used to kidnap people right in front of everyone. Ninety percent of security is good now. Citizens notify us about bad people in the area.”

“Is Baghdad ready to stand on its own?” I said.

“No,” she said, “of course not,” as if my question was frankly absurd. None of the American soldiers in the room argued with her assessment, neither in front of her nor later after we left.

“We won’t be ready until young people replace the older generation in the Iraqi Army and Iraqi Police,” she continued. “They need to replace the old Baath Party members who are still inside.”

Paul Bremer dissolved what remained of the Iraqi Army after he was made the head of the Coalition Provisional Authority by the Bush Administration in 2003. He wanted to purge Iraq of its Baathists and old regime loyalists. A large number of Baathists, though, were Baathists in name only. They weren’t necessarily ideological. Party membership was required of government employees, and a huge number of Iraqis worked for the government. Bremer’s dismissal and blacklisting of these people radicalized many. Some joined the insurgency. It was a bad call on Bremer’s part, and he did it despite warnings from his advisors about what might happen if he went through with it.

He faced a formidable problem, even so. What is to be done about Iraq’s leaders and functionaries who cut their teeth in a totalitarian political system? Malath, like many others, thinks Iraqis will have to wait for them to retire or die.

“There is also way too much fighting between Iraqi political parties,” she said. “And there are too many parties.”

“How many parties are there?” I said.

“There are more than 100,” Sermad Mahmoud said.

Sergeant Franklin cut in. “There are not more than 100,” he said. “That’s a total exaggeration. I’m not exactly sure how many there are, but it’s nowhere near that many.”

Sergeant Nick Franklin

“What should the American people know about Iraq that they don’t currently know?” I said, addressing my question to both Sermad and Malath.

“Iraqi people are friendly and follow the old Iraqi traditions,” Malath said.

I can vouch for this. There should be no question that this is true.

“And the government is so corrupt,” she said. “We don’t like them at all.”

I should point out here, again, that I was in the Adhamiyah sector of Baghdad, which is mostly made up of Sunnis. Iraq’s government is mostly run by Shias. Iraqi Shias are much happier with the government than Iraq’s Sunnis, and Malath is a Sunni. Still, she is right about corruption in the government. Most Sunni, Shia, and Kurdish politicians are corrupt.

“What is the local opinion of the Iraqi Police?” I said.

Sergeant Franklin had told me earlier that most Iraqis in his area don’t like or trust the police.

“People here don’t feel comfortable talking to them,” she said. “They are Shias from Sadr City, and they are corrupt.”

She’s right about that. Shia officers were brought in from Sadr City to police Sunnis. In Fallujah and Ramadi, the Iraqi Police were much more effective and more trusted because they worked in the same community they lived and grew up in.

“How, exactly, are the Iraqi Police here corrupt?” I said.

“If we ask them about detainees,” Sermad said, “they don’t answer unless we pay them to answer. A guy was recently released from jail because he bought his way out.”

Iraqi Police officer

“When did Al Qaeda move in?” I said.

Adhamiyah was a stronghold of support for Al Qaeda in Iraq until somewhat recently.

“They came in November of 2005,” Malath said. “They used young people and jobless people, and they lured them in with money. There were no jobs. It’s better now because the government opened a center for jobless people.”

“We helped the government do that,” Sergeant Franklin said. “We started weekend training classes where people can learn a trade like carpentry or secretary work.”

“What was it like here in 2004 and 2005,” I said, “before Al Qaeda moved in?”

“There was a militia here called Al Jihad,” Sermad said. “They came from Syria and Saudi Arabia. Then Al Qaeda moved in. They originally called themselves the Islamic State in Iraq.”

“Has public opinion here changed about American soldiers since Al Jihad and Al Qaeda came in?” I said.

“Yes, definitely,” Malath said. “Many people here like American soldiers now.”

“Can you describe the old opinion of American soldiers?” I said. “And what caused the change?”

“Al Qaeda used to control people’s minds,” she said. “They said Americans just wanted to control Iraq, and we believed them. We know now that it isn’t true. Americans have been helping a lot.”

“So public opinion changed about Al Qaeda, as well?” I said.

“Yes,” she said. “I mean, we didn’t like them before, but we agreed with them about some things. And anyway we couldn’t talk about them before, not until Sons of Iraq was created.”

Her nephew brought all of us more glasses of tea.

“Iraqi elections have all been corrupt,” she said.

“How so?” I said.

“Terrorist groups and outside organizations threatened people and assassinated their political enemies,” she said.

“Speaking of outside organizations,” I said, “what do people here think about Iran?”

“Iran has lots of influence,” Sermad said. “They support the militias, Jaysh al Mahdi, and the Badr Corps. They support some of the Iraqi parliament members. Iran is going to invade Iraq as soon as American soldiers withdraw.”

“He’s talking about a sort of generalized fear,” Sergeant Franklin said. “They don’t necessarily believe that is going to happen, it’s just something they are afraid of.”

“The Iraqi parliament members will invite the Iranian Army,” Malath said.

Malath and Sermad were being slightly hysterical. Like many Iraqis, they inflated threats all out of proportion to their actual size. Iraqis did the same thing when American soldiers first came. The U.S. invasion was compared, in the minds of many Iraqis, to the vicious Mongol invasion in the 13th Century.

“Do you think Prime Minister Maliki is an ally of Iran?” I said.

“He didn’t used to do the best thing for Iraq,” Malath said. “He is better now, but only because Americans forced him to conduct the operations against Shia militias. He used to say the Sons of Iraq was a Sunni militia.”

Maliki can’t credibly say any longer that Sons of Iraq is a Sunni militia, although some Western journalists still haven’t figured that out. Sons of Iraq is on the payroll of Maliki’s government. According to Major Mike Humphreys, “60 percent of its members in Baghdad are Shias”:http://www.michaeltotten.com/archives/2009/05/the-future-of-i-1.php.

“I have one more question about a completely different topic,” I said.

“Okay,” Malath said.

“Is there any chance that Iraq will have normal relations with Israel in the future?” I said.

Sergeant Franklin leaned over and whispered to me. “Most Iraqis don’t think that far outside the box,” he said.

I knew that already, but he was right to remind me. Israel is about as removed from Iraq’s problems as Sri Lanka.

“Iraq has no issues with Israel,” she said, “but it depends on the next Iraqi president.” Then she paused and gave me a more honest answer. “Personally, I don’t want normal relations with Israel.”

“Why not?” I said.

“Do you know about the situation with the Palestinians?” she said.

“Of course,” I said. “Everyone does.”

“I disagree,” Sermad said. “We should have normal relations with Israel. There is no reason we shouldn’t.”

Because of Israel’s remoteness to Iraq’s problems, the topic isn’t nearly as much of a red line there as it is elsewhere in the Middle East. Every Iraqi Kurd I have ever spoken to about Israel wants peace, normal relations, or even a strategic alliance. Arab opinion is mixed, but Arab Iraqis don’t seem to be afraid of arguing about it with each other. Some Lebanese want normal relations with Israel, but they don’t feel comfortable saying so because anti-Israel opinion in some quarters there is ferocious.

The electricity went out all of a sudden. The room went dark. This was Iraq, and Iraqis still don’t get anywhere near 24 hours of electricity.

There was a huge demonstration just south of Malath’s house shortly after we left. Thousands of radical Shias streamed out of Sadr City and surged up the main road into Sunni Adhamiyah. They screamed slogans in support of Moqtada al Sadr and what’s left of his Mahdi Army militia.

*

American soldiers can’t do much more in Iraq at this point. General David Petraeus’s counterinsurgency program is finished. He achieved a major breakthrough when he embedded infantry soldiers inside Iraqi neighborhoods and ordered them to place the security of the residents above their own. Recently, according to the requirements of the negotiated Status of Forces Agreement, American soldiers have been ordered out of Iraqi cities and back onto the large bases outside. Iraq’s urban areas — where most Iraqis live — will now have to stand or fall on their own.

Before the withdrawal, Lieutenant Eric Kuylman invited me to join him and his men again while they conducted a foot patrol in one of the older districts of Adhamiyah. This was one of the last patrols I joined up with in that country.

We came across a rubble-strewn site where it appeared a building might have once stood. Two soldiers swept for IEDs with a wand that whined like a metal detector in the airport.

Searching for IEDs in rubble, Adhamiyah, Baghdad

An elderly Iraqi man nervously sidled up to Lieutenant Kuylman. “Is there a bomb in there?” he said.

“Nah,” the lieutenant said. “We just check empty lots like this just in case. Don’t worry about it. There’s no more reason to think there’s a bomb in there now than there was five minutes ago.”

The man watched as the soldiers continued sweeping the pile of rubble.

“Hey,” Lieutenant Kuylman said to the Iraqi. “I’m trying to learn a few things about the neighborhood here. Can you tell me who has been living in the area the longest?”

“I have been living in this house,” he said and gestured toward the dwelling behind him, “for forty years.”

“Can we speak to you in private?” the lieutenant said.

“Of course,” the man said. “You are welcome.”

He opened the door and beckoned us in.

“Thank you,” I said. He shook my hand warmly with both of his hands.

“Please,” he said and gestured for us to sit on his couch.

His wife smiled and brought us tea. I didn’t see any children or younger adults in the house.

The couple seemed genuinely friendly. All Iraqis I’ve met are at least superficially friendly, but these two seemed especially so.

“I like to find the people who have lived in the neighborhood the longest,” Lieutenant Kuylman said. “If there are any people you don’t feel comfortable with around here, I will go talk to them. And I want you to feel comfortable telling me.”

“It’s quiet here,” the man said. “And if there are any problem, we will solve them amongst ourselves.”

“Really?” Lieutenant Kuylman said. “Who’s the mediator?”

“We have a guy who is like a sheikh,” the man said. “He settles these problems between people. Sheikh Zawi.”

“Ah,” the lieutenant said. “I know him. He’s a good guy.”

The elderly couple had a huge hand-made Persian carpet in the living room. It would fetch around $6,000 dollars in the United States.

“When Americans come into our houses,” the man said, “people outside want to know what’s going on.”

“What do people think is going on?” I said.

“That Americans are investigating or exchanging information,” he said. “Our traditions require us to welcome Americans into our homes.”

“Does it cause a problem for you if we come into your house?” I said.

“No, no,” the man said. “Everyone here knows me and knows my personality.”

An enigmatic response. Adhamiyah is a predominantly anti-American neighborhood. Was the man saying his anti-American credentials were solid, that no one would be concerned he was cooperating with the enemy? Or was I reading too much into it? Adhamiyah may be anti-American, but the people there are much more opposed to Al Qaeda and other insurgent groups than they are to the United States. And the man did approach us in the street. He introduce himself voluntarily and was concerned about bombs.

“There are going to be a lot of changes all across Baghdad,” Lieutenant Kuylman said. “We’re trying to push the Iraqi Army and Iraqi Police and get your system to work. We’re here to help, but we try to make sure the Iraqi Army and Iraqi Police have first done everything they can before we step in.”

Searching a car for weapons, Adhamiyah, Baghdad

“I want to relay a message to you,” the man said. “Hopefully the Iraqi forces will join us together. No Sunnis. No Shias. When I go outside Adhamiyah, I don’t trust the Iraqi forces.”

“Why not?” I said.

“You have to check the backgrounds of men in the Iraqi Army and the Iraqi Police,” the woman said. “There are a lot of bad people trying to work for them.”

“Do you have any names for me?” Lieutenant Kuylman said.

She didn’t have any names. Neither did her husband. All they had was a sense of dread and foreboding.

“When I hear about the schedule for American forces leaving Iraq,” the man said, “I get scared. I hope we get a nice life here in Iraq and that you can make it home safe.”

Lieutenant Kuylman winced. “There might be some growing pains.”

The woman flung her hands up toward the ceiling.

Post-script: You tip waiters in restaurants, right? I can’t go all the way to Iraq and write these dispatches for free. Travel in the Middle East is expensive, and I have to pay my own way. If you haven’t donated in the past, please consider contributing now.

You can make a one-time donation through Pay Pal:

[paypal_tipjar /]

Alternatively, you can make recurring monthly payments. Please consider choosing this option and help me stabilize my expense account.

[paypal_monthly /]

If you would like to donate for travel and equipment expenses and you don’t want to send money over the Internet, please consider sending a check or money order to:

Michael Totten

P.O. Box 312

Portland, OR 97207-0312

Many thanks in advance.

The Future of Iraq, Part III

Advertisement

Join the conversation as a VIP Member