Many third world cities look better at night than during the day. Darkness hides shabbiness. You have to imagine what the city actually looks like. If you live in a first world city yourself, you might fill in the blanks with what you’re familiar with. It’s only during the day that you can see just how run-down the place really is.

Baghdad isn’t like that. Baghdad looks worse at night because you can barely see anything. When your mind fills in the blanks, real and imagined roadside bombs, militiamen, booby traps, and snipers lurk in the shadows.

The city can be spooky at night. Millions of people live in Baghdad, but it’s dark after hours. Few lights illuminate the mostly empty sidewalks and streets. The city’s electrical grid is still offline half the time and must be replaced. Homes without generator power are dark more often than not, and almost everyone who owns a generator turns it off when they go to sleep. Baghdad after sundown is as poorly lit as a remote mountain village.

But it’s not a remote mountain village. The sound of gunshots is still a part of the general ambience. You’d be surprised by how quickly you get used to hearing them. They’re like background noise as long as they aren’t too close and you aren’t the one being shot at.

While walking the sidewalk of the Adhamiyah district with United States Army Second Lieutenant David Dimenna’s patrol unit, I heard three pistol shots in rapid succession from just a few blocks in front of us, followed by a fourth.

“Iraqi Army?” Lieutenant Dimenna said.

An Iraqi civilian passing by looked concerned. “There’s a checkpoint down there,” he said.

Another civilian walked past us as though nothing had happened. He was used to the sound of gunfire in Baghdad.

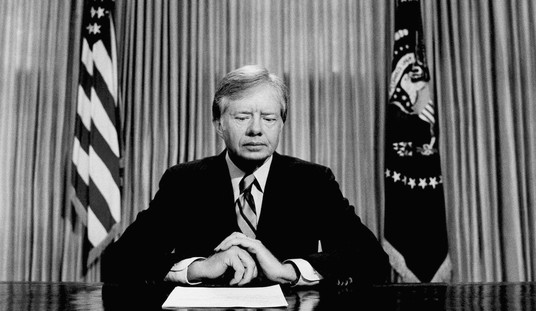

Second Lieutenant David Dimenna

These days when American soldiers hear gunshots, they assume the shots were fired by Iraqi Army or Iraqi Police. Iraqi security forces are famous for bad trigger discipline. They enjoy firing shots into the air, and they regularly shoot themselves and each other on accident. Lieutenant Dimenna still took the shots seriously, though. We were in Baghdad, after all, which, despite the dramatic reduction in violence, is still a dangerous city.

We climbed into Humvees. Lieutenant Dimenna called FOB (Forward Operating Base) Apache and reported the gun shots. We drove without headlights on Baghdad’s dark streets. His men had night vision. I had to rely on my eyes.

The area where the gunshots came from was nearly as dark as a forest at night. An Iraqi Police truck parked just up ahead flashed its red and blue lights.

Lieutenant Dimenna stepped out of the Humvee and spoke to one of the officers.

“We didn’t fire the shots,” one of the Iraqis said. “Maybe it was the Iraqi Army.” He gestured up the street by tipping his head. “They have a checkpoint right there.”

“Okay,” Lieutenant Dimenna said. “Good to see you, but we have to go check that out.”

I couldn’t see the Iraqi Army checkpoint in the dark and wouldn’t even have known it was there if the officer hadn’t told us it was there.

“I don’t know who fired the shots,” one of the Iraqi Army soldiers said when we got there. He pointed toward a dark and creepy abandoned building just up the street. All I could see was its silhouette against a backdrop of stars. “I think they came from in there.”

Somebody fired gun shots within two block of an Iraqi Army checkpoint, and they didn’t bother to find out what happened? If I were alone and distressed in Iraq, I would hate to have to count on those guys to save me.

A Blackhawk helicopter flew overhead and fired countermeasure flares out the sides designed to divert heat-seeking surface-to-air missiles. They sounded like fireworks.

Surface-to-air missile countermeasures fired from a Blackhawk, Adhamiyah, Baghdad

Though we could have walked to the abandoned building in less than two minutes, we drove in the Humvees.

My eyes were beginning to adjust to the darkness, but I could still barely see. The only reason I know what the street looked like is because I took pictures. My camera sees better than I can in the dark if I hold it still long enough to take a photo with the shutter held open.

I wondered if we were going inside the building. I wouldn’t be able to see anything in there, and I didn’t relish the thought of joining Lieutenant Dimenna and his men while they chased an armed man through its black hallways.

We parked in front and got out. I heard two middle-aged men speaking in Arabic, though I couldn’t see them. They were Iraqi Army.

“A drunk guy walked past here,” one of them said. “He was talking shit, and he assaulted one of my officers.” He said they wrestled the man to the ground and arrested him after firing off a couple of shots.

“I’m glad to hear he was detained,” Lieutenant Dimenna said. “But let’s see if you can arrest people without firing your weapons.”

*

Iraq’s capital looks dark at night from the air. It’s no giant brightly-lit circuit board, as most cities are. It looks, instead, like a dense night sky reflecting on a brilliant sea. You can’t see the streets because there are so few lights. Most houses go dark after nightfall. The only lights you can see are from houses with generators where the family hasn’t yet gone to bed. The city is perhaps only one percent as lit at night as cities anywhere else.

Lieutenant Dimenna and his men chose an intersection at random and set up a temporary checkpoint. Every passing car was pulled over and searched. Military age men were politely asked to step out of their vehicles and frisked. Civilians are no longer allowed to carry weapons in Baghdad. They won’t be arrested if they’re caught, but the weapons will be taken away.

Embedding with the United States military in Baghdad at the end of the surge is no longer like risking your neck in a war zone. It’s more like going on ride-alongs with the police. But it’s not like riding along with the New York police, or even with the Mexico City police. Baghdad is still Baghdad. While no longer a city at war, it’s not exactly peaceful and normal yet either.

The young men pulled from their cars didn’t seem to mind being patted down by foreign soldiers, but I imagined they did.

Lieutenant David Dimenna pats down a young Iraqi man, Adhamiyah, Baghdad

“Outwardly they seem to be okay with it,” Lieutenant Dimenna said, “and they know it’s to keep the area more secure.”

The Adhamiyah district is one of the more liberal in the city, but it’s still conservative even compared with other Arabic capitals. More than 90 percent of the people I saw outside were men, and more than 90 percent of the women I saw wore a headscarf over their hair or an enveloping all-black abaya.

Lieutenant Dimenna said there were a few bars in the area, but I didn’t see any. And they’re nothing like the stylish bars of Beirut and Tel Aviv. “They’re called casinos,” he said. “Only men go there, and most of them are hard surly drinkers. They go to play cards and drink and sit on the couches in back.”

After searching cars for twenty minutes or so, we got back in the Humvees and drove. My thoughts, as usual when driving around in Iraq, turned to roadside bombs. It’s not scary. The odds of actually being hit are quite low, especially now. I found it impossible, though, to keep my mind entirely off IEDs.

Bridge over the Tigris River, Adhamiyah, Baghdad

“What are we doing now, exactly?” I said after a few minutes.

“Driving around aimlessly,” our driver said.

Lieutenant Dimenna sat in the front passenger seat.

“We’re just out being seen,” he said, “and making sure nothing bad is going on. It’s good that things are quiet, but it’s also hard. It’s hard looking for IEDs when we know there aren’t many around.

Cows crossed the street in front of us. Cows, in the middle of a city of more than six million people. I couldn’t imagine seeing cows other, smaller regional cities like Beirut, Amman, or Kuwait. In Cairo, perhaps, at least on the outskirts. Baghdad is like a large village in many ways, though at least it’s less tribal than Iraqi villages.

Suddenly we were driving through a nice neighborhood with larger homes, a little more light, a great deal less trash, and lines of palm trees on each side of the street. It looked pleasant at night. Perhaps daylight would reveal ramshackleness I couldn’t see.

I didn’t see many bullet holes, and I saw even fewer houses and buildings that had been destroyed. Ruined houses were easier to spot in Fallujah, and I saw whole swaths of central Ramadi that had been flattened, but most of Baghdad looked like it was never at war. Whenever my thoughts turned dark in Baghdad — which happened sometimes — I tried to remember how much worse it used to be in Ramadi, and that Ramadi today is sort of okay. Iraq was careening toward oblivion in the beginning of 2007, yet it’s still in one piece.

Even if security were up to regional standards — and make no mistake, it is not — Baghdad still isn’t a place where most people would want to go on vacation. Its historic sites are a mess.

Clock tower, Adhamiyah, Baghdad

Restaurants are almost entirely limited to basic chicken and kebab places — nowhere you would want to take a date. If fine dining establishments and cafes exist in Baghdad, I’ve never seen them. I don’t mean to be a snob about the place. That’s just how it is. Iraqis have more important things to worry about than bringing their “third places” up to international standards. Fancy restaurants would likely just get car-bombed now anyway. If I were a businessman living in Baghdad, I wouldn’t even think about opening one until a few years from now at the earliest.

We got out and walked past a shop destroyed by a car bomb a week before I arrived.

Aftermath of a car bomb, Adhamiyah, Baghdad

A massive IED exploded at an Iraqi Army checkpoint just one block away at the same time.

“The IED didn’t kill anybody,” Lieutenant Dimenna said. “No one was manning the checkpoint when it went off. We do things a little differently from the Iraqis. We relieve men in place. If their shift ends, they go home whether the next guys are there to take over or not.” Those Iraqis who left their post early were saved by their laziness.

A kid ran up to us, as kids so often do in Baghdad.

“Can I have my guns back?” he said to Sergeant Pennartz. “I want to shoot chickens.”

“We gave you back the shotgun,” Sergeant Pennartz said. “But you can’t have the other guns back. They’re against Iraqi law.”

The kid’s grandfather had given him an Ottoman-era shotgun worth more than 20,000 dollars. An Iraqi court made an exception to the law and let the kid keep it.

“Sometimes the system works,” Lieutenant Dimenna said.

The kid asked me to take his photo while he posed with Sergeant Pennartz.

“I took guns from your house,” Sergeant Pennartz said to the kid, “and now we’re friends?”

Lieutenant Dimenna gave the kid a tip card with a phone number on it and asked him to have his family to call if they see anything suspicious.

“Sometimes people do actually call,” he said to me.

*

The U.S. Army was conducting what it called “census work,” where soldiers knocked on doors at random and asked residents their names, their occupations, and a couple of security questions. Citizens selected for visits had no choice but to let the soldiers in, though they were always asked nicely as if they did have a choice.

A man wearing pajamas opened the first door we knocked on and squinted at us. His hair was messed up, and he looked annoyed. I wanted to apologize for bothering him.

“Yes,” he said, “please, come in, welcome.” He spoke perfect English. I could tell by the tone in his voice that he didn’t want us in his house. He didn’t seem hostile, just irritated that he was forced to get out of bed.

Lieutenant Dimenna rattled off his list of questions: How many people live in this house? What are all your names? Where does everyone work? How many cars do you have?

The man’s adult son came downstairs and said hi. He did seem happy to see us, but the old man was still peeved. I felt like an intruder. I didn’t take pictures. I didn’t even ask if I could take pictures.

“What’s your biggest concern in the area?” Lieutenant Dimenna said.

“Security, of course,” the man said. “But also services. Electricity, water, and sewer. The condition of the streets. Everything is terrible.”

“Do you have any specific security concerns?” Lieutenant Dimenna said.

“It’s a lot better in general,” the man said. “I don’t have any specific concerns. Our community is educated and everyone knows each other here. So it’s quiet.”

The man was given a tip card with a phone number to call if he wanted to report any problems.

We left and began the exact same routine at a house across the street where all the lights were turned off.

A soldier rang the bell. Nobody answered. Another soldier loudly banged on the metal gate with his gloved fist. He made a hell of a racket. I cringed and felt horrible. Everyone on the block surely could hear us, and at least half of them asleep. I didn’t want to go in. I would have preferred to stay outside and not bother people who were trying to sleep. But what if something interesting happened?

A young man emerged from the house and opened the gate. He didn’t seem annoyed in the least, despite the fact that we had obviously woken him up.

A 60 year old woman in a hijab sat us down on couches in the front room.

I was surprised by how nice the house was on the inside. Homes in Iraq are almost always nicer on the inside than the outside suggests. It surprises me almost every time I walk into one, no matter how many times it happens. The public environment in Iraq is a vast slum, but interior private homes and lives are much richer. It’s hard sometimes to figure out where a real slum begins and ends in Iraq.

We didn’t take off our boots even though Iraqis don’t wear shoes in their homes. Soldiers can’t take their boots off in Iraq, nor can I take off mine if I’m traveling with them.

The young man was a student, and his father was a professor. They sat on a couch opposite me and Lieutenant Dimenna.

The lieutenant asked the usual questions.

“Our biggest concern,” the professor said, “is security and war.” That’s what almost everyone in Iraq says when asked this question. Government corruption, trash, too few hours of electricity — these are still secondary concerns. I don’t think I’ve ever heard an Iraqi say “the economy” when asked what ails his country, even though the economy is in horrendous condition. There are worse things in the world than not having much money.

I didn’t even go inside the third house during the census-taking part of the mission. The soldiers were intrusive enough by themselves, and the routine was dull. Few seemed happy to see us. It was night. I was tired and wanted to get some sleep myself.

So I stayed outside and talked to Sergeant Pennartz who stood watch on the porch.

“I sure hope this holds,” he said, “because we’re going to pull out soon. I think it’s a mistake. This country is going to need help for years. But at the same time I really really really don’t want to come back here. That’s how a lot of us feel. We don’t want to pull out, but we also don’t want to be here. I just hope the peace holds so we don’t have to come back and fight for the ground we already won and abandoned. Again.”

Another soldier — I did not catch his name — asked me if I wanted an energy drink.

“Hell, yes,” I said. “Please.” What I really wanted was an espresso.

He took a Rip-It from a cooler in the back of the Humvee and passed it to me.

“We’re having a competition,” he said, “to see who can drink the most Rip-Its on a single patrol. So far the record is seventeen. Starting Monday we’re going to see if anybody can make the double dozen.”

“On the surface everyone will tell you Sunnis, Shias, we don’t care, we’re all Iraqis,” Sergeant Pennartz said. “But talk to them for a while and they’ll tell you what they really think. Do you know what those Shias did? Et cetera. Some Sunnis say Shias were never in Iraq until the Iran-Iraq war. Some are totally ignorant and say they’ll never live next to Shias.”

We eventually climbed back in the Humvees and headed back toward the FOB. On the way I saw orange trees covered in dust behind crumbling walls. Wild dogs ran in the streets. Iraqi Police officers huddled around a fire to keep warm like bums around a burning trash can in The Bronx.

“Sometimes,” Lieutenant Dimenna said, “during the worst of the rainy season, the sewage here gets up to ankle level.”

*

“I think they’ve given up trying to fight us,” Staff Sergeant Christian told me back at the FOB. “They finally learned they can’t beat us. All hell broke loose in Sadr City this spring, but they got their asses kicked and finally decided to just let us build our wall.”

He meant the Gold Wall. It cuts off the southwestern third of Sadr City from the rest. American soldiers patrol that southwestern third, while the Iraqi Army maintains exclusive control of the northeastern two-thirds. The famous Jamilla market area is in the American sector, and it’s economically rebounding now. The wall was built last spring when Mahdi Army insurgents who infested the Jamilla Market area were pushed just far enough away from the center of Baghdad that they could no longer fire their limited-range rockets into the Green Zone.

Another wall with an entirely different purpose was built in Adhamiyah, and it has been there much longer. Most of Adhamiyah is Sunni, and it’s adjacent to hostile Shia areas. When sectarian violence between the two communities peaked, the U.S. Army erected a three-mile long wall with gigantic concrete barriers to keep Shia militants out. Vehicle checkpoints were placed at every entry into the neighborhood. The wall was controversial at first, but sectarian violence dramatically plunged. Normal life — as much as life can be normal in a dysfunctional city like Baghdad — returned to the area. Most early critics of the wall did a re-think.

“The Adhamiyah wall will stay in place until further notice,” Major Mike Humphreys said. “It channels traffic. The people in Adhamiyah know who is supposed to be there and who isn’t. There have been suggestions to take the wall down, but people who live there like it now. Lots of people in Sadr City want the Gold Wall gone, but business owners want it to stay up.”

“People are pretty friendly now,” Sergeant Christian said. “They invite us dinner. Hell, they invite us to parties. Back in 2005?” He laughed. “There’s no way.”

“The biggest threat in our area is Al Qaeda,” Sergeant Manuel Juarez said. “It’s mostly Sunnis here. AQI [Al Qaeda in Iraq] targets the Sons of Iraq because they’re trying to destabilize Baghdad. Sometimes Sons of Iraq guys fight other Sons of Iraq guys. There is a lot of stupid tribal and personal crap going on.”

Sons of Iraq are local security men organized by the United States military for neighborhood watch and checkpoint work. They have since been absorbed by the government of Iraq. Most are being trained for regular army and police work.

“There aren’t any car bombs in the market,” Sergeant Juarez continued. “The streets are too narrow and they can’t get cars in. A Sons of Iraq guy was recently killed by a car bomb outside the Hanifa mosque, but it’s generally been safer since we laid siege to Sadr City. Enemy contact is pretty minimal these days.”

“Everyone seems cool,” he said. “We haven’t seen anyone too angry. It’s hard to read people, but their friendliness does seem genuine. It’s gotten better. As you can see, some of these buildings are shot up, but that wasn’t our doing. They were already like that when we arrived. Back in 2004 and 2005, we really got jacked here.”

“We do find some IEDs,” Sergeant Nick Franklin said, “but they’re mostly targeting the Sons of Iraq. We found one two days ago, though, outside an abandoned house that I think was targeting us. Sniper attacks are the biggest threat. We lost a guy in September to a sniper. We get car bombs once in a while, but they are targeting Iraqi civilians. It’s AQI going for the big bang.”

I joined him and his unit on a daytime patrol.

Sergeant Nick Franklin

“We need to pick up Sons of Iraq witness in a shootout that happened a few days ago,” he said. “I’m thinking I should arrest him just to make sure he actually shows up in court.” I think he was joking.

His men set up a temporary checkpoint at an intersection in a residential neighborhood. He chose that location because he knew his witness could often be found there.

Sure enough, he was there. And he agreed to show up in court the next day.

Sergeant Nick Franklin (right) and Sons of Iraq witness (left)

“So you didn’t need to arrest him,” I said. I had to speak loudly because the power was out in the neighborhood and half the houses on the street had their generators turned on. It sounded like two dozen people were mowing their lawns at the same time.

“He might have enough on this guy we’ve been after for a while,” he said. “But we don’t want to pick him up if we can’t get enough evidence. We’ve been detaining guys lately who’ve been back on the streets after six months. Apparently, killing Americans will only get you six months in jail in Iraq.”

“What do they have to do to get put away longer?” I said.

“They have to get caught with actual contraband,” he said. “IEDs and car bombs.”

“Imagine,” I said, “spending only six months in jail for blowing people up with anti-tank mines in the States.”

We loaded up in Humvees, and I rode with Sergeant Juarez.

Sergeant Manuel Juarez

“Right here is the place to go for grub,” he said as we passed a chicken stand.

“You guys eat out here?” I said.

“Hell, yeah,” he said. “There’s a guy up the street who will sell you a hamburger for a dollar.”

“Are the burgers any good?” I imagined they would not be.

“Well,” he said. “They’re Iraqi. But I’ll pay a dollar for one.”

Many of the streets in the neighborhood were unpaved. Raw sewage ran in rivulets down the center of many.

“Local contractors were hired to fix these problems,” he said, “but they took the money and ran.”

I snapped a few pictures out the window.

“We’re going to go through the market,” he said. “We need to avoid this one particular Sons of Iraq guy. He whines about everything and will suck up hours of our time complaining.”

“What does he whine about?” I said.

“Pretty much everything,” he said. “We took their AKRs away from them recently and he whined about that for hours.”

Our convoy of Humvees rounded a corner and entered an older part of the neighborhood.

“That guy with the green shirt,” Sergeant Juarez said, “makes the best chicken. He uses wood instead of that rotisserie shit. It’s not like the fucking mesquite we have in the States, but it’s good.”

A young woman walked next to our Humvee as we drove.

“Oh shit, she even waved at us!” the driver said. “I figure we have to plant the seed early,” he joked, “so that in a few years we can date them.”

We parked and got out of the trucks.

“So, what’s the plan?” I said to Sergeant Franklin.

“Our purpose,” he said, “is population engagement and information engagement operations. We’re handing out flyers about bad guys. Most end up in a fire or in the garbage, but sometimes people use ’em. Kids like to collect ’em like they’re trading cards, and they always make sure they get one.”

A flyer telling kids to throw their garbage into a trash can

“The majority don’t want to us to leave,” he said.

“How do you know?” I said, unsure if I should really believe it.

“They tell us one on one,” he said. “We tell them the country has to sink or swim at some point. They don’t like the Iraqi Police or the Iraqi Army. The Iraqi Police used to kidnap and murder people. The Iraqi Police at JSS Adhamiyah won’t go on patrols unless we make them. They’re pretty much useless, but at least they’re less dangerous now that we’re watching them. Some civilians here say they want us to stay forever because things are better with us around. They don’t necessarily want us out in the streets every day, but they do want us somewhere in Iraq.”

Houses near the market were older than most in the area. They weren’t surrounded by walled courtyards as most are in Baghdad. Front doors were just barely set back from the streets and the alleys. The neighborhood could be rather charming if it were fixed up; and it had more Eastern character than the modern parts of the city.

The covered market, though, was a horror.

Clouds of flies swarmed the vegetables.

A thin river of foul water and sewage flowed in the walkway. I smelled the tang of rotting garbage and piss.

“Most attacks against us these days are retaliatory,” Sergeant Franklin said. He didn’t seem fazed by the disgusting conditions. I guess he was used to it. “It’s not all organized Al Qaeda around here anymore. We haven’t had any complex attacks against us lately.”

When we emerged from the market, he gently ribbed our Iraqi interpreter Tom. Tom was not his real name. All Iraqi interpreters use pseudonyms to conceal their identity from potentially dangerous locals. “We went into a house recently and Tom neglected to tell me a woman was scrubbing the floor with her shirt off.”

“Was she wearing a bra?” I said.

“Nope,” he said. “She was topless. Tom here is a dirty young man.”

Tom grinned.

I was happy to get a look at Baghdad without having to worry overly much about my own safety. Many reporters who stayed away from Iraq during the surge in 2007 and 2008 but went back at the end said they could hardly recognize Baghdad any more, that it was a different city. Those reports raised my expectations too high. It didn’t look all that different to me. There were more people out on the street. The security situation had been completely transformed. But the city was otherwise as run-down and corrupt and generally dysfunctional as it was before.

We passed beneath a rat’s nest of electrical wires. A transformer sizzled and popped over my head and blue smoke curled upward.

*

“Do you have anybody you want to arrest?” I said to Lieutenant Michael Kane before I joined his men on a patrol in the area.

“Actually, yes,” he said. “There’s an old Baathist guy who sometimes gives us intel. A few days ago he called and said he wants to come in and talk, but he doesn’t want anyone to see him coming back to the FOB. So he asked me to arrest him in front of everybody.”

Lieutenant Michael Kane

“A fake arrest then,” I said.

“That’s what he wants us to do,” he said. “It seems unnecessary to me, but it’s his deal.”

We set off to find him at dusk. The sun had gone down and there wasn’t much light left in the sky.

Our convoy of Humvees parked on a muddy side street. We got out and walked. A long row of private generator stations that supplied electricity to several houses were set up along this muddy street. Our Baathist guy said he would wait for us near one.

“Make sure you don’t photograph his face,” Lieutenant Kane told me.

“Of course,” I said. “I wouldn’t think of it.”

We waited next to one of the gigantic neighborhood generators. It was enclosed in a shed and made so much noise it was hard to hear what anyone said. Our former Baathist guy wasn’t where he said he would be. Lieutenant Kane peeked inside the shed. No one was in there.

I felt slightly uneasy. Something in the air just gave me the creeps. What if we had been set up? Perhaps an anti-personnel bomb was inside the shed. If a bomb had been planted to take out me and the soldiers, no one else in the neighborhood would be hurt. We were isolated. I stepped away from the shed just in case, but no one else did.

“Maybe he’s at the other end of the street,” Lieutenant Kane said. Most Iraqis gave terrible directions. One American officer I spoke to said the Iraqi Army and Iraqi Police would be twice as effective if only they could learn to read maps. Sometimes they get lost at night in their own cities and neighborhoods.

We walked down the street. The former Baathist informant was waiting for us outside a different generator shed. Three of his friends were there with him.

Lieutenant Kane stiffly walked up to him as though he were furious and might punch him.

“Hey!” he said. “You’re under arrest!”

The man threw his hands into the air.

“Flex-cuff him,” Lieutenant Kane said to one of his men.

Our informant was gently led up against the cinderblock wall and flex-cuffed.

The man’s three Iraqi friends looked terrified.

“I won’t arrest you,” Lieutenant Kane said, “as long as you tell me everything you know about him.”

“I don’t know anything!” one of them said.

“Do you know why I’m arresting him?” Lieutenant Kane said. “He’s a JAM guy.” JAM is short for Jaysh al Mahdi, Moqtada al Sadr’s radical Mahdi Army militia. “What the fuck is he doing around here?”

“I don’t know!” said another of the Iraqis.

“Where does he live?” Lieutenant Kane said.

All three Iraqis pointed at the same house at the exact same instant. I would have laughed out loud if they had pointed at different houses, but they gave up their buddy without even blinking.

“If you can give me some info,” he said, “I can pay you good money.”

“We are Sons of Iraq,” one of them said. “We’ll tell you anything you want. But we have a problem. Checkpoint Ten is out of ammo.”

“You guys are taking the ammo we’re giving you and selling it,” Lieutenant Kane said. “Did you get into a fight I don’t know about?”

“We fired at the national guard,” the man said.

“What the fuck?” Lieutenant Kane said.

Lieutenant Michael Kane questions men in the Sons of Iraq program

“They wouldn’t stop at the checkpoint,” the man said. “We didn’t know who they were.”

“You guys have to be careful!” Lieutenant Kane said. “They’re Iraqi Army. You need to be keeping your ammo. And don’t shoot at the Iraqi Army!”

“We also need ammo at Checkpoint Eleven.”

“Where’s that ammo going?”

“We only have one magazine per AK-47.”

“That’s all you need.”

The Baathist informant was blindfolded and stuffed into the back of a Humvee, and we drove away. When we got back to the FOB I saw that his blindfold had been removed.

“Are you okay?” Lieutenant Kane gently asked him as we walked toward the compound from the parking lot.

The man smiled and nodded, but he looked ill at ease.

*

Lieutenant Kane was in charge of security in Eastern Adhamiyah. “Our area is a really shitty poor area,” he told me.

Adhamiyah, Baghdad

Eastern Adhamiyah is also sometimes a creepy area.

“It was a real JAM Special Groups hotbed area,” he said. “Now it’s mostly just low level shitheads. AQI is still around, too.”

Both Sunnis and Shias live in Eastern Adhamiyah.

They used to call one area “JAM Alley.” Shortly before I arrived one of their Humvees was hit with an EFP, an Explosively Formed Penetrator, the most terrifying IED ever designed. EFPs fire liquid copper plates faster than bullets at passing vehicles. The molten metal cuts through Humvees and tanks as though they were made of Jell-O. Few things in Iraq gave me the creeps as much as driving on a road with a known EFP threat.

“That last EFP slug was a close call,” Lieutenant Kane said. “It skimmed the turret on the Humvee and ripped through some trees. Fortunately, nobody was killed.”

Terrorist and insurgents aren’t the only creepy people around. He once saw a deaf kid tied to a tree in someone’s back yard.

Thousands of Iraqis mounted a huge demonstration against the Status of Forces Agreement, or SOFA, between the United States and the government of Iraq in Eastern Adhamiyah. SOFA allows American soldiers to remain in Iraq for a few more years, although combat soldiers will have to evacuate Iraqi cities to the perimeter in June. Naturally the anti-SOFA protest erupted in the eastern part of the neighborhood. It has long been more hostile than the other parts of the area. Lieutenant Kane said some kids still throw rocks at Americans there, although that never happened while I was around.

Our foot patrol began at an Iraqi Police station. Several local officers were scheduled to come with us. Most patrols these days are conducted by Americans and Iraqis at the same time.

I didn’t hear much praise for these officers. Local civilians are afraid the police and the army will trash their houses and beat them up if they’re arrested. American soldiers aren’t happy about that, and they have additional complaints I didn’t hear from Iraqis.

Lieutenant Kane and two Iraqi Police officers speak to a civilian in Adhamiyah, Baghdad

“They’re having tribal problems at checkpoints,” Lieutenant Kane said. “One tribal leader was about to tell everyone to go get their AK-47s because one of his men got searched by a Sons of Iraq guy from a different tribe. Lots of Sons of Iraq guys won’t search their friends. I tell them I don’t care if it’s their father at the checkpoint — search him.”

Iraqi Police officers still routinely fire negligent discharges in the stations.

“I forgot my AK was loaded, one of them said to me recently after he damn near shot his foot off,” Lieutenant Kane said. “I asked him why he was carrying it by the trigger. That’s how I always carry it! he said.”

Lieutenant Kane rolled his eyes.

“They’re like Keystone cops,” said another soldier.

“Some go out of the station with their helmets on the back of their heads and their shoes untied,” Lieutenant Kane said. “They’re like kids.”

“Just wait until they’re running this place by themselves,” I said.

“I don’t even want to get into that,” he said. “Some of these guys completely freaked out last week when Iraqi Army soldiers fired a warning shot near them. Their eyes got huge, and they were like, whoah.”

“This is Iraq,” I said. “They aren’t used to that yet? I’m used to it and I don’t even live here.”

“Then there are other people,” he said, “who shrug when bombs go off in their neighborhood as long as their windows don’t get blown out. They say oh, it’s just a bomb, it’s not a big deal.”

Iraqi Police officers have a narrow job description. They don’t handle mundane domestic disturbances like Western police officers do. Some Iraqis look, then, to Americans.

“One woman’s husband was being a total asshole,” Lieutenant Kane said. “She came to us and said he makes bombs. I said does he really? She looked down and said no. I asked her why on earth she would say something like that if it isn’t true. I guess he was beating her up, but we’re not equipped to handle domestic problems over here.”

Trash is still all over the damn place in Baghdad. There isn’t as much of it as there used to be. The much-touted progress is real. But progress in a place like Iraq is relative.

“Iraqis are happy when they see Americans picking up trash,” Lieutenant Kane said.

“Why do they throw their trash everywhere, then?”

“It’s mostly out of habit,” he said. “You’ve seen these new blue dumpsters around?”

I had.

“One guy complained about all the trash in the neighborhood, but I later saw him throw his own bag of trash next to the dumpster. And the dumpster was empty. He could have played frigging racquetball in there.”

He wanted to do more “census” work. We knocked on doors and sat in various living rooms for ten minutes.

I no longer felt so intrusive, although we were no less intrusive than when I was sensitive about it. I had gotten used to it, and the soldiers were even more used to it.

“Some people won’t give out information unless we check every house on the block,” Lieutenant Kane said. “And they often won’t talk to us unless we’re inside their houses.”

His men confiscated AK-47s from two houses in a row. “Sorry about this,” he said to the owners. “You aren’t allowed to have these by order of Prime Minister Maliki.” I didn’t see anyone get into trouble for having weapons. They just weren’t allowed to keep them.

One of the Iraqis who was forced to hand over his AK had a wild mane of hair and a shifty look in his eyes. His wife served us small glasses or orange juice as most of us sat in the living room. Two soldiers searched upstairs.

“Sir!” one of the soldiers called out. “This guy has a 50 gallon barrel of gasoline on the roof. And he does not have a generator.”

I wondered then if my orange juice was poisoned. It was an absurd and paranoid thought, but it’s hard not to think that way at least once in a while in Baghdad. Just before we set out on this patrol, I was told not to touch any gas cans on the sidewalk. A few days earlier someone tried to pick one up, but it was too heavy. He then noticed it had wires sticking out the sides that led to a detonator hidden somewhere.

Woman on roof, Adhamiyah, Baghdad

No men were home in the next house. Three middle-aged women and two elderly women welcomed us into the living room. One of the middle-aged women looked nervous. Her hands shook and she swallowed hard. A five-year old girl ran up and clutched her leg.

“She’s scared,” her mother said. “We moved here last year from Ur. A Stryker force there kicked in our gate while looking for Ali Babas.”

“Don’t worry, don’t worry,” Lieutenant Kane said. “We’re not here to hurt you.” He smiled and waved at the child. The little girl stared at him and stayed behind her mother’s leg.

“Are you going to take our money?” the woman said.

The lieutenant looked pained.

“We’re not going to take any of your things,” he said. “We’re not going to take your money. I promise. We’re just talking to people in the neighborhood and searching for illegal weapons.”

The woman relaxed slightly. But only slightly.

“We don’t have any weapons,” she said.

“Okay,” Lieutenant Kane said. “I believe you.” Nevertheless, some of his men searched the house for illegal weapons. “Are you having any security problems in the neighborhood?”

“No, no,” the woman said. “There are no problems here.”

“How about your daughter at school? Want me to go beat up some bullies?”

Big laughs all around as Lieutenant Kane grinned. The worried woman seemed to feel more at ease now.

“Does your daughter get good grades?” he said. “Is she going to be prime minister one day?”

“No!” yelled every woman in the house at the same time. “No! No politics! No!” They were genuinely horrified by the suggestion. Politics is not an honorable profession in Iraq. Maybe it never will be.

On our way back to the FOB, we drove through the Qahira neighborhood. “There used to be tons of Mahdi Army posters in this neighborhood,” our driver said.

“We took them down one night at three in the morning,” Lieutenant Kane said. “And we put Iraqi Army posters up in their place. Those got taken down immediately, but the Mahdi Army posters never came back. Nobody said anything about it in public, but it was different when we went inside private houses. Thank you, they said. Thank you. Thank you for taking those down..”

Post-script: You tip waiters in restaurants, right? I can’t go all the way to Iraq and write these dispatches for free. Travel in the Middle East is expensive, and I have to pay my own way. If you haven’t donated in the past, please consider contributing now.

You can make a one-time donation through Pay Pal:

[paypal_tipjar /]

Alternately, you can now make recurring monthly payments through Pay Pal. Please consider choosing this option and help me stabilize my expense account.

[paypal_monthly /]

If you would like to donate for travel and equipment expenses and you don’t want to send money over the Internet, please consider sending a check or money order to:

Michael Totten

P.O. Box 312

Portland, OR 97207-0312

Many thanks in advance.

Baghdad in Fragments

Advertisement

Join the conversation as a VIP Member