When I first noticed Alliance Theological Seminary Professor Louis DeCarro Jr.’s essay entitled “Why White Evangelicals Should Claim John Brown” in Christianity Today, I was at first puzzled and then bewildered that the evangelical magazine would even consider publishing such a piece.

My bewilderment stemmed from the fact that reading DeCarro’s essay brought back a lot of memories from an earlier phase of my life when I had occasion to spend a great deal of time combing through and thinking critically about the mid-1970s scholarship on John Brown.

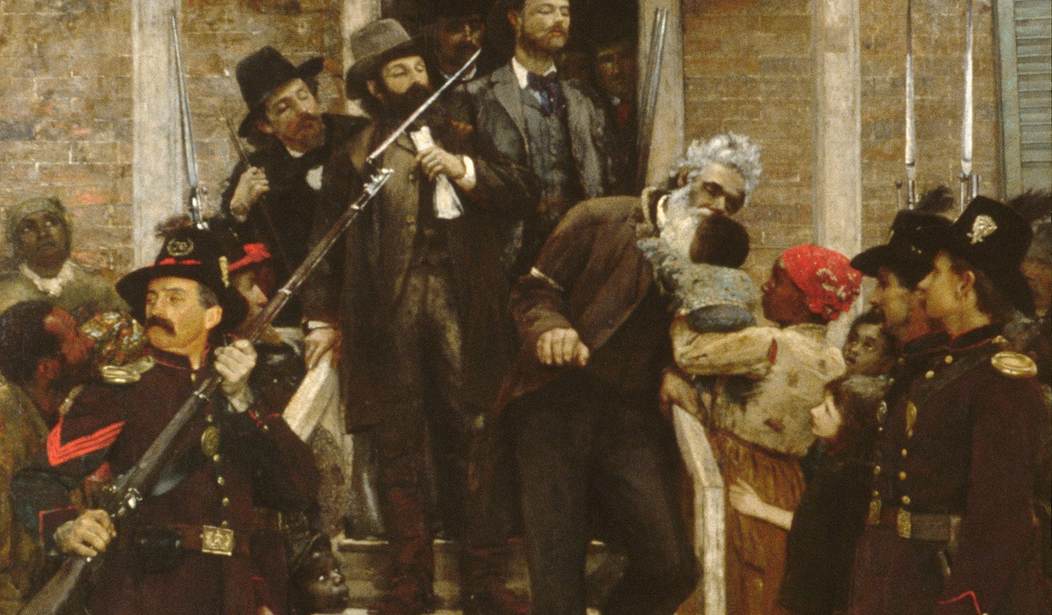

That period required, among much else, many long hours in the Library of Congress on Capitol Hill reading microfiche (hey, it was pre-Internet!) copies of the coverage and commentary in the nation’s top newspapers of that day concerning the raid on Harper’s Ferry, the fiery leader’s trial and execution, and the meaning of his death for a nation then clearly headed for a civil war.

Unfortunately, my intended doctoral dissertation on “John Brown and Gnostic Millenarianism in the American Political Regime” only made it to a third draft before being left unfinished, thanks to the more immediate summons of two Reagan presidential campaigns, congressional staff jobs, and service as a Reagan appointee in the 1980s.

Even so, to this day I know aspects of John Brown’s life that apparently escaped Professor DeCarro and which render as absurd and dangerous his encouragement that evangelicals adopt as a hero the author of the Pottawatomie Massacre in 1856 and the Harper’s Ferry Raid of 1859.

DeCarro offers such encouragement because, he writes, “white evangelicals seem to be in dire need of good examples of people who were transformed by their faith to rise above pedestrian racism — because, not in spite of, their unshakable commitment to the authority of Scripture.”

Related: The Remarkable Story of ‘God’s Smuggler’

No, John Brown is not a hero, for reasons I hasten to add that have nothing to do with the issues of racism in contemporary America or slavery in the Antebellum Period of American history, and everything to do precisely with his abuse of Scripture.

The reality is that John Brown’s religious zealotry obscures for present-day promoters like DeCarro a man who was in fact a vicious killer and a political radical with a seething desire for dictatorial power.

The significance of John Brown’s religious zealotry is rooted in his tragic misunderstanding of Hebrews 9:22, a misunderstanding that is expressed most succinctly in his final written words before being taken to the gallows and death.

Hebrews 9:22 declares, according to the English Standard Version (ESV), that “indeed, under the law almost everything is purified with blood, and without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness of sins.”

John Brown wrote in a note he handed to his jailer just before being hanged on Dec. 2, 1859, that he “was quite certain that the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood. I had as I now think: vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed; it might be done.”

This was not the first time John Brown had spoken such words. From Hebrews 9:22, he had concluded years before that in the political realm, blood must be shed to atone for the sins of a nation.

Such a view utterly contradicts the evangelical understanding that the only blood that suffices to cover the sin of an individual is that of the resurrected god-man, Jesus Christ, and that His followers should demonstrate their salvation with hearts transformed by grace in lovingly serving their brothers and sisters in the church, family, and community. The Old Testament concept of national atonement through blood sacrifice was ended by Christ’s death on the cross.

Demonstrating Christian love was clearly not on John Brown’s mind in Kansas in 1856 when he, several of his sons, and three fellow travelers, enraged by the sacking of Lawrence by pro-Southern settlers in the territory, kidnapped five such men from their families along Pottawatomie Creek and then hacked them to death with machetes.

And whatever else John Brown may have thought would be dramatized by the immense bloodshed and death he knew would result from his doomed raid three years later on the federal government’s armory at Harper’s Ferry in Virginia and the slave revolt he thought it would inspire, Christian love was not to be thereby demonstrated.

Like so many radical ideologues who would come after him in the 20th century, John Brown viewed the shedding of blood as an essential means to an end, that end being his possession of unchallenged political power. This reality is best illustrated by the constitution he drafted, which was adopted with few changes by the delegates to the Chatham (Canada) Convention.

The two dozen delegates to this rump assembly were followers John Brown had picked up along the way in Kansas and thereafter on his road to Harper Ferry. The document they adopted tells us what their commander-in-chief intended to do once the slave revolt was underway.

The Chatham document has the appearance of having the same three branches as the U.S. government, but one need not dig too deeply to realize the appearance is a sham. The constitution was called “provisional” for good reason — it was to be changed whenever John Brown decreed.

The key to understanding the Chatham document is the role of the Commander-in-Chief, the Cromwellian office Brown clearly intended for himself. Article IV describes the executive branch as having a president and a vice-president, but then comes Article VI on the “validity of enactments,” specifying that:

“All enactments of the legislative branch shall, to become valid during the first three years, have the approbation of the President and of the Commander-in-chief of the army.” Were America under the Chatham document today, Joe Biden and Gen. Mark Milley would be sharing duties as co-executives.

That the Commander-in-Chief would in reality function as the decisive authority is obvious from Article XXVIII, which specifies that “all captured or confiscated property and all property the product of the labor of those belonging to this organization and of their families, shall be held as the property of the whole, equally, without distinction, and may be used for the common benefit, or disposed of for the same object …”

Guess who controls all of the captured property and property created by the labor of those under the Chatham document? Article XXIX decrees that “all money, plate, watches, or jewelry captured by honorable warfare, found, taken, or confiscated, belonging to the enemy, shall be held sacred to constitute a liberal safety or intelligence fund … The treasurer shall furnish the Commander-in-chief at all times with a full statement of the condition of such fund, and its nature.”

In other words, the Commander-in-Chief, which is to say, John Brown, would have control of the military and the treasury — the power and the money. An odd choice indeed for an evangelical hero.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member