In September, Charlie Kirk was murdered.

What followed disturbed me almost as much as the crime itself. Not everywhere, not from everyone, but widely enough to be unmistakable, the reaction on the left was celebratory. Celebrities joked. Writers sneered. Ordinary people rushed to explain why he had it coming. He was labeled a hatemonger, a danger, a man whose absence improved the world.

What struck me most was not simply the cruelty, but its direction. The pain was not accidental. It was aimed. His widow, his children, his friends, and the many fans and admirers who loved him were meant to feel it. The message was clear enough: this is what happens when you love the wrong person. Suffering was not collateral damage. It was part of the point.

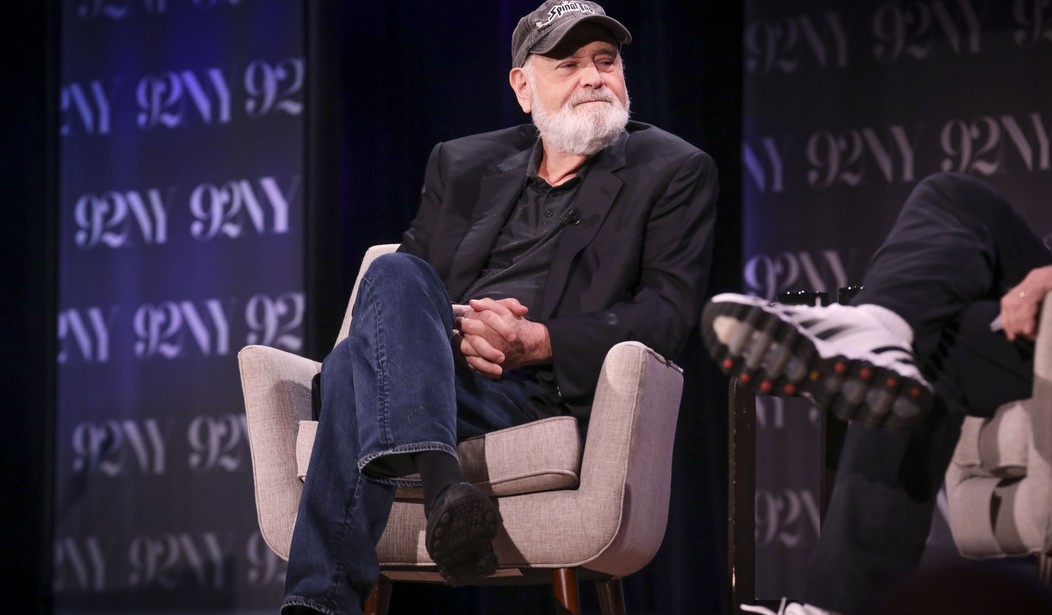

Last night, Rob Reiner and his wife were reportedly murdered.

Reiner made some genuinely great films. He also spent years speaking about conservatives with open contempt. He could be dismissive, cruel, and dehumanizing in his rhetoric. None of that is in dispute. But what unsettled me was how familiar the reaction felt. Almost immediately, I am seeing people on the right respond in much the same way I had seen people on the left respond to Kirk’s death: with jokes, with glee, with the thin satisfaction that an enemy had finally been removed.

Different politics. Same behavior.

These reactions are not opposites. They are mirrors. In both cases, death was treated as a moral verdict. A human life was reduced to a symbol. The dead were spoken of as though they had never been fully human to begin with, as though their deaths closed an argument rather than ending a story, and it's an argument they lost.

Dehumanization

This is not grief, justice, or accountability. It is dehumanization.

The justifications are always ready at hand. He deserved it. She was evil. The world is better off. These phrases are meant to make cruelty feel principled. But dehumanization is not ideological; it is behavioral. It spreads easily, and it looks the same no matter which flag it wraps itself in.

Death matters morally in a way few other moments do, because death is final. It is the endpoint, the completion of the story of a human universe, and what follows is a mystery known only to that person's soul and to God. Only at death do we truly lose options: the ability to apologize, to make amends, to create something new, to actively love one another. Nothing can be revised at that point. Nothing can be repaired.

That is why death is always a tragedy, even when the person who has died caused real harm. The tragedy deepens when wounds remain unhealed, when apologies were never offered, when reconciliation never came. It is understandable, in that moment, to lash out — to rehearse grievances, to savor the last word that can no longer be answered. After all, you cannot fix a relationship when someone is dead.

But indulgence is not strength.

Lashing out at the dead is a confession of powerlessness. It is the refusal to face what can still be changed: yourself, your conduct, your world, and the way others are persuaded to see it. The dead cannot answer back. They cannot grow. They cannot repent. Stripping them of their humanity apparently costs nothing in the moment, which is precisely why it is so tempting.

Dignity

It also costs us nothing to refuse to celebrate death. No reputation, no power, no leverage. Silence and restraint suffice. No one is required to mourn publicly, to forgive privately, or to pretend that harm was not done.

But indulging in contempt does, in fact, cost us something real. It trains us to see people as disposable. It teaches us that dignity is conditional, something granted only to those who agree with us or belong to the right side. And once that lesson is learned, it does not stay neatly confined to our enemies.

By refusing to strip someone of their humanity, you grant them dignity, and in doing so, you take on that dignity yourself. You assume weight. You place yourself under a moral standard rather than above one. You place our shared humanity exactly where it belongs: at the center of things, not at the mercy of our grudges.

This does not require forgiveness. It does not require pretending the dead were innocent, kind, or unjustly criticized, and it does not require that you agree with a single thing they ever said or did. Acknowledging humanity is not excusing harm. It is simply recognizing that, for good or ill, the person who has died was human and subject to the same limits, failures, and moral complexity as the rest of us.

That recognition is an act of restraint. And restraint, at moments like this, is a form of grace.

The Cost

Two deaths. Two ideological camps. Two waves of reaction that looked disturbingly alike.

In both cases, the temptation is the same: to treat death as a victory condition, to savor the feeling that an enemy had been silenced. The justifications differ. The behavior does not. In both cases, something essential is lost — not from the dead, but from the living.

A culture that cannot restrain itself at the moment of death is a culture that has lost its sense of proportion. Death is the one boundary no one crosses back over. When we turn it into a punchline, we reveal how thin our commitment to human dignity really is.

Grace, at moments like this, is not softness. It is strength exercised at the last possible moment.

It costs us nothing to take the high road.

It may cost us everything if we don’t.

Editor’s Note: May both Charlie Kirk and Rob Reiner rest in peace and may our memories of them eventually be mostly good, not bad.

Join PJ Media VIP and use promo code FIGHT to get 60% off your membership.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member