VDH: Pollsters Have No Reputation After This Decade-Long Hatred Of Donald Trump.

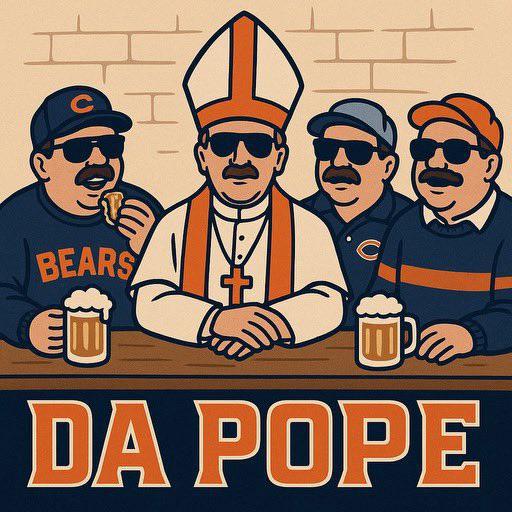

So what were the pollsters trying to tell us or were they trying to manipulate? And I think it’s the latter. Larry Kudlow, for example, the former Fox business, I think he still is at Fox, he pointed out that when he examined the New York Times and the Washington Post polls, they were deliberately not counting people who surveyed that they were Trump voters in 2024.

That was half the country. They were only polling about a third. Think of that, a third of the people that said they voted for Trump, they polled.

Not half. So of course their results were going to be disputed or suspect. But here’s another thing.

There were analyses after each of the 2016, the 2020, and the 2024 elections about the accuracy of polls post-facto of the election. And we learned that they were way off in 2016. They said they had learned their lessons.

They were way off in 2020. They said they learned their lesson. And they were way off in 2024.

And why are they way off? Because liberal pollsters, and that’s the majority of people who do these surveys, believe that if they create artificial leads for their Democratic candidates, it creates greater fundraising and momentum. Kind of the herd mentality.

Joseph Campbell explores: How Trump can turn the tables on the pollsters.

Were he to choose a more focused, accountability-driven response, Trump could readily point to flawed poll results reported in the 2024 presidential campaign. Given that many of them erred in estimating the election outcome, he could pose a simple question: What makes them believable now?

Trump, in short, could argue pollsters have persistent credibility problems and point to vulnerabilities exposed in recent elections.

Traditionally, pre-election polls have been regarded as representing what George Gallup, a founding figure of survey research, called an “acid test” of the soundness of polling techniques. “The only justification of an election forecast,” Gallup once declared, “is to test polling methods.”

The late Philip Meyer, a well-regarded journalist, educator and past president of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, essentially agreed with Gallup’s characterization, noting: “A poll is an estimating device while an election is an exact measurement of the real world. By holding the device against the reality, we can learn how well the device is working.”

The reality revealed in the three most recent U.S. presidential elections was that pollsters were unable to measure with accuracy Trump’s popular backing. They collectively understated support for Trump in each election, despite having made methodological adjustments following the 2016 and 2020 campaigns — adjustments specifically intended to measure Trump’s popular backing more accurately.

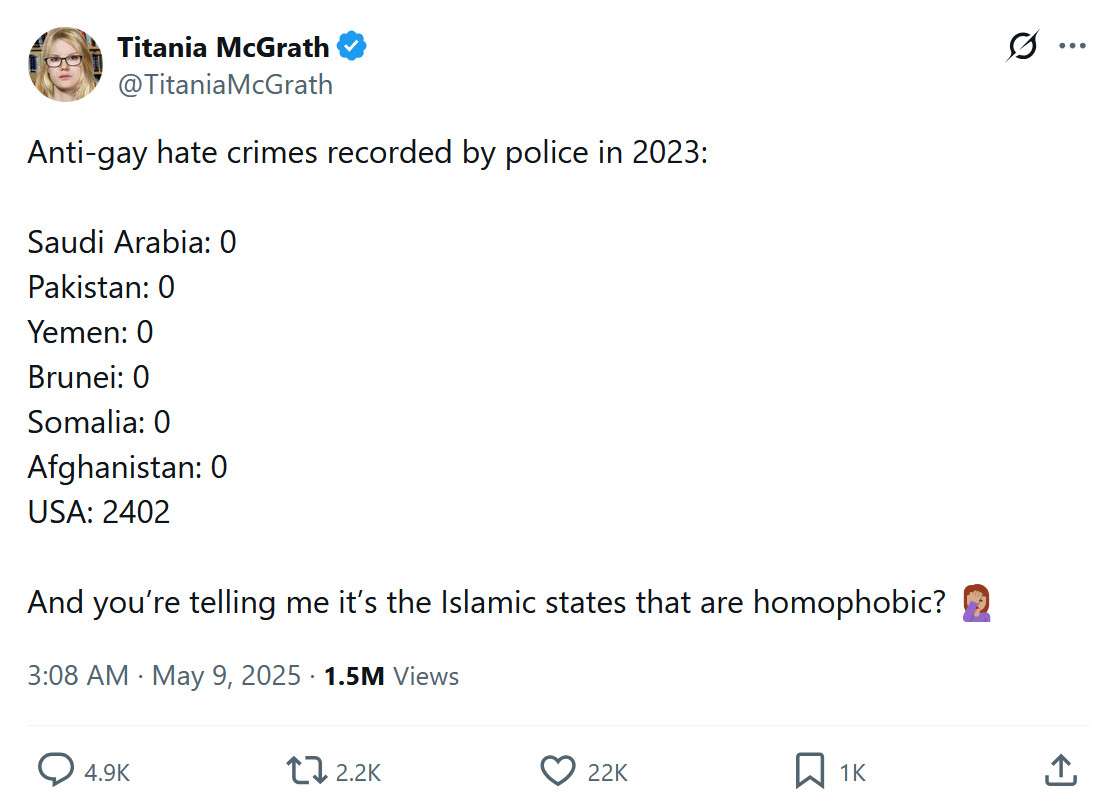

Finally, in “Sins of omission,” Salena Zito explores the DNC-MSM hatred of Real Clear Politics’ aggregation of polls because they favored the Bad Orange Man:

In the final stretch of last year’s presidential election, the New York Times took a whack at RCP, suggesting its map showing Trump winning all seven swing states was inferior because it was using subpar polls.

“Overall, Trump has made slight gains in the national polling average over the past two weeks, and the battleground state polling averages have tightened,” the story read. “Still, the race remains uncommonly close.”

Unlike its competitors, RealClearPolitics does not filter out or weigh polls that its critics allege are “low quality.” RCP likes to say that “at RealClearPolitics, high-quality polls are accurate polls.” One of its pages displays a map of the Electoral College with a winner projected for each state, even those the site currently deems to be toss-ups.

The story then said that “influential accounts have been sharing screenshots of RealClearPolitics’ scarlet-dominated Electoral College map,” often pairing it with images of a betting average site showing Trump with a 65% chance of winning.

Simon Rosenberg, a Democratic strategist and constant critic of RCP, said in the story that he believed that Republican-aligned pollsters were “flooding the zone” to shift the polling averages and deflate Democrats’ enthusiasm.

In the end, FiveThirtyEight had then-Vice President Kamala Harris with a 50-in-100 chance of winning the cycle. RCP had Trump winning six of seven battleground states. The New York Times implied that it had gamed to look better for Trump with “low-quality polling.” This isn’t hyperbole; it was in the headline that read: “Why the Right Thinks Trump Is Running Away With the Race.”

Two things appear to be happening here — the sin of omission by skipping over who the true inventor and innovator of the craft was and an effort to dismiss its competency and capability.

The job of a news organization is to attract an audience because its content is consistent in getting it right or pretty darn close*. The same is true of polling. It is one thing to question polling firms and say you don’t like their methodology or think they’re rigorous enough.

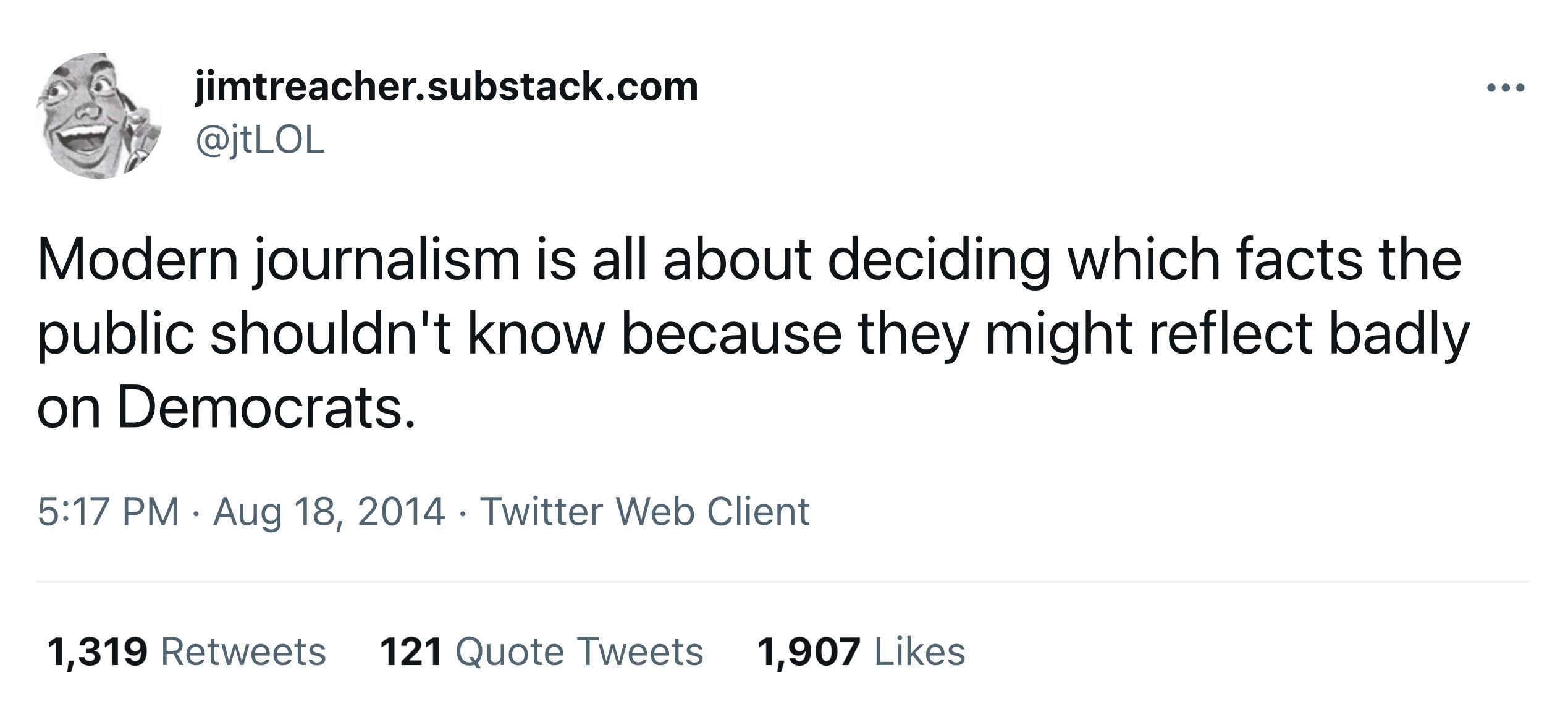

Well, that’s what the job of a news organization used to be. In the 21st century, that’s shifted somewhat: