Despite his death at age 70 in 1999, Stanley Kubrick remains a cult favorite among millions of cinephiles, as shown by the recent 50th anniversary big screen re-release of his 1968 masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey in both 70mm and IMAX formats. The ambiguity of 2001 drove its first audiences crazy — at its premiere in Los Angeles in April of 1968, Rock Hudson was heard to shout, “Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?!”

From Dr. Strangelove onward, Kubrick loved ambiguity as a filmmaker, telling Joseph Gelmis, his interviewer in the 1970 book The Film Director as Superstar, that “a certain degree of ambiguity is valuable, because it allows the audience to ‘fill in’ the visual experience themselves. In any case, once you’re dealing on a nonverbal level, ambiguity is unavoidable.” Kubrick also practically admitted he had no problem lying to interviewers about his films, when he told Rolling Stone’s Tim Cahill while promoting Full Metal Jacket in 1987, “Some people can do interviews. They’re very slick, and they neatly evade this hateful conceptualizing. Fellini is good; his interviews are very amusing. He just makes jokes and says preposterous things that you know he can’t possibly mean.”

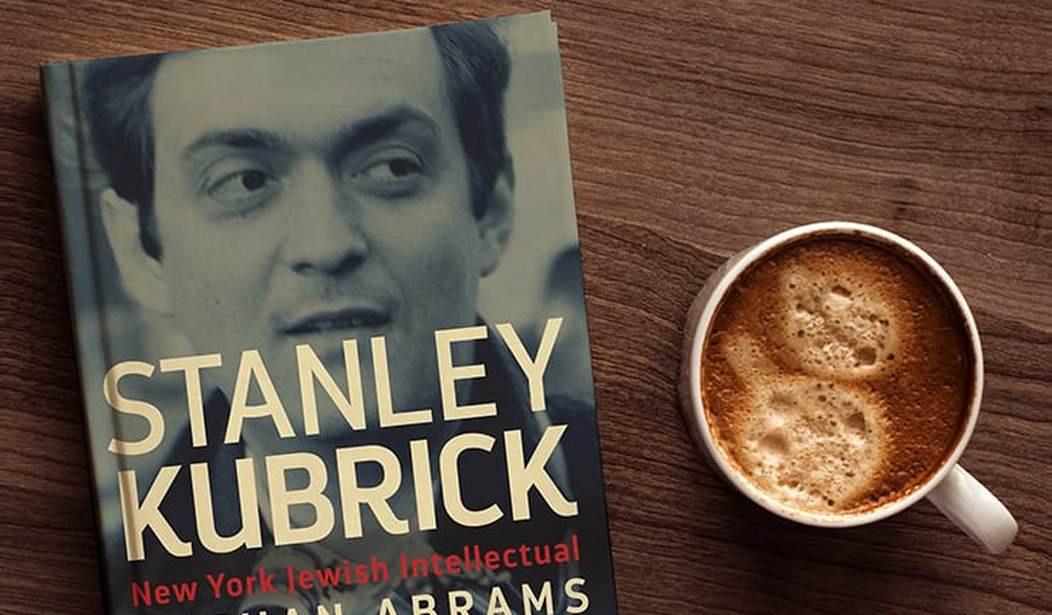

In Stanley Kubrick: New York Jewish Intellectual, Nathan Abrams, a professor of film studies at Bangor University in Wales, makes a very convincing case that while Kubrick posed as an atheist technocrat filmmaker who wanted his films to appeal to worldwide audiences, among the many things he was burying in their subtexts were “the concerns of Jewish intellectuals in the post-Holocaust world.” According to Abrams, two themes repeat in various forms in virtually all of Kubrick’s movies: menschlikayt and goyim naches.

Regarding the first of the two Yiddish expressions, Abrams writes that menschlikayt, derived from the term mensch, originally meant a:

“[U]niquely Jewish ‘code’ of conduct,” emphasizing the moderate, meek, and intellectual values of Yiddishkeit (literally: Jewishness/Jewish culture, which John Murray Cuddihy defined as “the values, feelings, and beliefs of the premodern shtetl subculture . . . ‘Jewish fundamentalism’”). It privileged a posture of reliance on family, tradition, accommodation, nonviolence, gentleness, timidity, and a man’s responsibility for his fellow men in contrast to conventional goyish (“un/non-Jewish/Gentile”) masculinity.

Abrams notes, later in his book, that Kubrick, with more than a little assistance from Kirk Douglas (formerly known as Issur Danielovitch Demsky), began to push hard against the original concept of “Menschlikayt,” towards a more muscular post-WWII version. But in its original definition, Abrams writes that “Menschlikayt rejected goyim naches”:

Literally meaning “pleasure for/of the gentiles,” its root is the Hebrew word goy (singular of goyim, meaning gentiles), but it also derives from the word for “body” (geviyah). It can therefore also be interpreted to mean a “preoccupation with the body, sensuality, rashness, and ruthless force,” as manifested in such physical activities as bearing arms, horse riding, dueling, jousting, archery, wrestling, hunting, orgies, and sports in general. Denied the right to participate in such activities, Jews instead denigrated them, consequently also disparaging those very characteristics that in European culture defined a man as manly: physical strength, martial activity, competitive drive, and aggression.

In his early chapters, Abrams explores Kubrick’s beginnings, shortly before the end of WWII, as a hustling teenage still photographer for Look magazine. (Abrams notes that Kubrick wasn’t above rearranging elements into a more newsworthy or controversial shot, a tacit reminder that the “Fake News” isn’t exactly a new phenomenon by what we now refer to as “the MSM.”) By the early 1950s, Kubrick cut his teeth in the motion picture industry with a few documentaries for RKO, before moving on to his first features. After making The Killing in 1956 starring Sterling Hayden (which no less than Orson Welles said was better than John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle, an earlier caper flick that also starred Hayden), Kubrick came to the attention of the man who would give him his giant leap towards both superstardom and independence as a filmmaker: Kirk Douglas.

Kubrick And Kirk, “The Muscular Moses”

In 1956, Kubrick and James Harris, his then-producer, acquired the rights to a 1935 novel set in WWI by Humphrey Cobb called Paths of Glory. Douglas agreed to star in the film in exchange for a production credit for his nascent company, Bryna; and his star power sold the picture to United Artists. Abrams writes that the plot of Cobb’s novel, three French soldiers being railroaded towards execution for alleged cowardice in battle to set an example of the rest of the troops, “evoked that of the Dreyfus Affair a half century earlier”:

In October 1894 Alfred Dreyfus, the only Jewish officer in the upper ranks of the French army, was accused of spying for Germany and publicly disgraced. Convicted without evidence, he was stripped of his rank and sentenced to solitary life confinement. As he was taken away, crowds chanted “Death to the Jews.” It was a miscarriage of justice so profound that it divided France and beyond…Dreyfus died the same year Cobb published his novel.

According to Abrams, the project appealed to both Douglas and Kubrick as a way to overcome “age-old anti-Jewish stereotypes. Since antiquity, but particularly in the modern era, Jews were perceived as weak, passive, and averse to military involvement.” In contrast, Colonel Dax, as portrayed by the rugged macho Douglas, is shown both as a heroic soldier and a shrewd attorney. While the fate of the soldiers he is charged with defending against cowardice is a foregone conclusion, it’s not due to Dax’s lack of skill as a lawyer. And in Dax we also see the more modern personification of a Mensch. As Abrams writes:

He’s brawn and brains, as befitting a mensch. General Mireau (George Macready) describes him as “perhaps the foremost criminal lawyer in France.” General Broulard (Adolphe Menjou) refers to the “keenness of [his] mind.” Such designations define him by his intellect, possessing what is known, approvingly, in Yiddish as Yiddische kopf (Jewish brains), tapping into a trend, predating the invention of cinema, whereby Jews are stereotypically defined by their minds. Later, in cinema, the legal profession became a stereotypical marker of Jewishness. Twice in their initial exchange, Dax trips up Mireau, giving the impression that he’s much more intelligent than his superior officer.

In his next film, Douglas would star as what Abrams describes as “a muscular Moses,” aka Spartacus. Kubrick was brought in by Douglas after the film’s first scene had been shot, after Douglas had a falling-out with original director Anthony Mann. Spartacus’ success would be Kubrick’s springboard to independent filmmaking.

The 1960s: Finger on the Zeitgeist

Unlike Orson Welles, whose rococo post-Citizen Kane films rarely connected with a mass audience, and as a result, made him a pariah in Hollywood boardrooms, in the 1960s and early 1970s Kubrick seemed preternaturally connected to the mass culture zeitgeist of the times: 1962’s Lolita anticipated the sexual revolution of the Beatles-era; 1964’s Dr. Strangelove, the anti-Vietnam War protests and the left’s disgust with fellow Democrat Lyndon Johnson (who many likely viewed as a more cornpone version of George C. Scott’s General Buck Turgidson). And 2001: A Space Odyssey become the top grossing American film of 1968, in spite of its radical structure and lack of expository information, thanks to its eye-popping special effects, in service to visuals that managed to tie into two of that year’s biggest but very different obsessions: the moon race and psychedelic drugs. 1971’s A Clockwork Orange, a futuristic film shot on a shoestring budget, focused on violence and the proper role of the state’s response, topics many Americans were debating in the aftermath of the violent riots of the late 1960s and Kent State.

After his 1975 film Barry Lyndon, Kubrick’s output would slow to a crawl, with a gap of 12 years between his 1987 film Full Metal Jacket, and his last movie, Eyes Wide Shut, in 1999. Part of the reason for those long gaps are blind alleys such as Aryan Papers, his early 1990s attempt at writing a Holocaust-themed movie, which Kubrick shelved when he learned that his friend Steven Spielberg was about to helm Schindler’s List and AI, whose proposed complex digital special effects stymied Kubrick. But in addition to these dead ends, the increased delay in Kubrick’s output was caused by the preparation time of each successive film, not least of which was writing screenplays loaded with massive amount of subtext. But it’s their complex and layered subtexts that allow Kubrick’s films to be interpreted in numerous ways by their audiences and critics.

1975’s Barry Lyndon was Kubrick’s first big stumble as a mature filmmaker. Unlike his previous films, it lacked an obvious topical theme to resonate with audiences. Its failure ensured that Kubrick took fewer chances or less risk in his last three movies. Arguably, both 1980’s The Shining and 1987’s Full Metal Jacket were examples of genre deconstruction. The former, like Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, was an attempt by a superstar director to cash in on the horror genre. (Being based on a Stephen King novel, as King was in the midst of his own ascension to superstardom, didn’t hurt, either.) The latter, a war movie, with echoes of such earlier films as Apocalypse Now, The D.I., Jack Webb’s 1957 look at Parris Island, and Joseph Sargent’s 1970 counterculture cult hit Tribes, with Darren McGavin as a tough-as-nails Marine drill instructor and Jan-Michael Vincent as the hippie draftie he attempts to break. And of course, Kubrick’s last film, Eyes Wide Shut, based on a 1926 novella by Austrian Arthur Schnitzler, was sold to the public as a virtual orgy starring superstars Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman, helping to front-end load its success.

Kubrick, Kabbalah, and the Ultimate Trip

In 1973, Carolyn Geduld wrote Filmguide to 2001: A Space Odyssey for Indiana University Press, which is arguably the single best key to unlocking 2001: A Space Odyssey’s structure and many of its mysteries. Other critics would explore how its dead-eyed cipher-like futuristic characters are Nietzsche’s “Last Men,” until Keir Dullea’s victory over a Machiavellian supercomputer prepares him to be transformed into the Nietzschean Übermensch. But in Stanley Kubrick: New York Jewish Intellectual, Abrams makes a convincing case that in addition to Nietzsche, Kubrick was also obsessed with Kabbalah, an ancient branch of Jewish mysticism “with its emphasis on words, numbers, and numerology,” which had become increasingly popular in the postwar era. Abrams writes that “the great scholar of Kabbalah, Gershom Scholem’s.. .book On the Kabbalah and Its Symbolism was published in English in 1965,” just as Kubrick and co-writer Arthur C. Clarke were beginning their early drafts of what would become the film’s script.

The influence of Kabbalah, Abrams writes, can be seen, among many other places in the film, in its chapter titles:

Part three, “Jupiter Mission: 18 Months Later,” accords to the realm of Derash or Midrash. In this light, the name of the spaceship Discovery, which is a space probe on a voyage of inquiry, seeking the source of the monolith on Jupiter, is highly resonant. This section is laced with Hebrew symbolism. Eighteen in Hebrew is equivalent in numeric value to “life” (chai), referring to double the human period of gestation and birth. The silent prayer central to the Jewish daily service is also known as the Shemonah Esrei (Eighteen) because it contains eighteen benedictions.

* * * * * * *

Called “Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite,” the fourth and final section invokes the Kabbalistic concept of ein-sof, the Hebrew for “without end” or “the infinite”… It is by no means insignificant that the final words spoken in the film are “total mystery,” invoking a doctrine of faith or religious truth, as might be revealed by Kabbalah.

This is fascinating stuff, which adds yet another layer of complexity to 2001’s seemingly infinite (pun intended) subtext. But then, as I said earlier, all of Kubrick’s post-Lolita films have deep, deep subtexts that provide a cottage industry for both film critics and Kubrick’s obsessive fans (not least of whom is your humble narrator). 2001 also marked Kubrick’s first effort at going beyond dialogue as the primary method for advancing a story. As Kubrick told Joseph Gelmis in 1970:

I think one of the areas where 2001 succeeds is in stimulating thoughts about man’s destiny and role in the universe in the minds of people who in the normal course of their lives would never have considered such matters. Here again, you’ve got the resemblance to music; an Alabama truck driver, whose views in every other respect would be extremely narrow, is able to listen to a Beatles record on the same level of appreciation and perception as a young Cambridge intellectual, because their emotions and subconscious are far more similar than their intellects. The common bond is their subconscious emotional reaction; and I think that a film which can communicate on this level can have a more profound spectrum of impact than any form of traditional verbal communication.

Barry Lyndon: Kubrick’s Most Jewish Movie?

Lacking 2001’s dazzling special effects and the comedic drive and satire on contemporary culture embodied by Dr. Strangelove and A Clockwork Orange, Stanley Kubrick’s 1975 film Barry Lyndon is the film that separates the true Kubrick obsessive from everyday filmgoers. In his book, Kubrick, Inside a Film Artist’s Maze, Thomas Allen Nelson called it “A Time Odyssey.” The film is both a time machine back into 18th century Ireland and England and a look into fifty years or so of a man’s life, from his teen years to a dissipated middle age. In his 1975 article for industry publication American Cinematographer on Barry Lyndon’s painterly — and often ravishing — images, Herb Lightman wrote, “In its bare bones the rise-and-fall saga of an 18th-century Sammy Glick, Barry Lyndon is also practically a documentary of how people lived in the Ireland and England of that period – their manners and morals, their values and amours, the personal duels and large-scale battles.”

In his new book, Abrams notes that “in its depiction of social exclusion and isolation, critic Jonathan Rosenbaum called Barry Lyndon Stanley Kubrick’s most Jewish movie…Kubrick identified with Barry, perceiving in him an avatar”:

As an American Jew living in an English country house in rural Hertfordshire, Kubrick surely felt removed from the society that enveloped him, as somewhat of a social pariah. When Thackeray writes, “You who have never been out of your country, know little what it is to hear a friendly voice in captivity.” Kubrick surely empathized with the feeling of exile. “Clearly,” B. F. Dick writes, “Kubrick saw something of himself in the novel: the boy from the Bronx, now London based, who compensated for his lack of university education by acquiring a knowledge of the arts that few academics could match.”

After all, [Ryan] O’Neal was the only American among a European cast, much resembling Kubrick’s own position within a British film industry. Barry [Lyndon] is an outsider, a theme that has distinct parallels with Kubrick’s previous films. Kubrick, as we know, admired such types. Back in 1960 he had praised the “outsider who is passionately committed to action against the social order.” He was referring to such criminals, maniacs, poets, lovers, and revolutionaries as [earlier Kubrick characters such as] Johnny Clay, Dax, Spartacus, and Humbert. To this list can be added Alex and Barry. All were “outsiders fighting to do some impossible thing.”

* * * * * * * *

Barry has Yiddische kopf. While seemingly not bright or very articulate, he’s smart enough to keep his words to a minimum, to stay silent when required, and to maintain the required poise and facade. Largely living by his wits and resourcefulness until he marries Lady Lyndon, he’s verbally adept, able to charm people. Capable of adapting to survive, he ingratiates himself with both men and women alike. In his narcissism and verbal adeptness, he’s similar to Humbert and Alex, both of whom can be read, as we’ve seen, as Jewish.

In his chapter on A Clockwork Orange, Abrams’ efforts as seeing Alex as a cipher for Judaism seem somewhat shakier, but he makes a much more convincing case regarding Barry Lyndon. In the latter film, the themes of being an outsider dominate the story, all the way to we as an audience feeling distanced by our gazing into a painterly recreation of a egalitarian, pre-industrial revolution past that hasn’t existed for centuries.

There isn’t space in this already lengthy review to discuss Abrams’ look at all of Kubrick’s films, from his first documentaries in the early 1950s, to his final effort, 1999’s Eyes Wide Shut, which Abrams describes as Kubrick’s “most personal, autobiographical, and complex movie, particularly in terms of its and his Jewishness.”

Ultimately though, are Abrams’ assumptions correct? Many of them ring true and likely are. But let’s give the last word to the maestro himself, in a note to a critic who attempted to breakdown the subtext of Dr. Strangelove in 1965: “I would not think of quarreling with your interpretation nor offering any other, as I have found it always the best policy to allow the film to speak for itself.”

Join the conversation as a VIP Member