Update (3/29/17): The second part of this article is online here, with many additional photos.

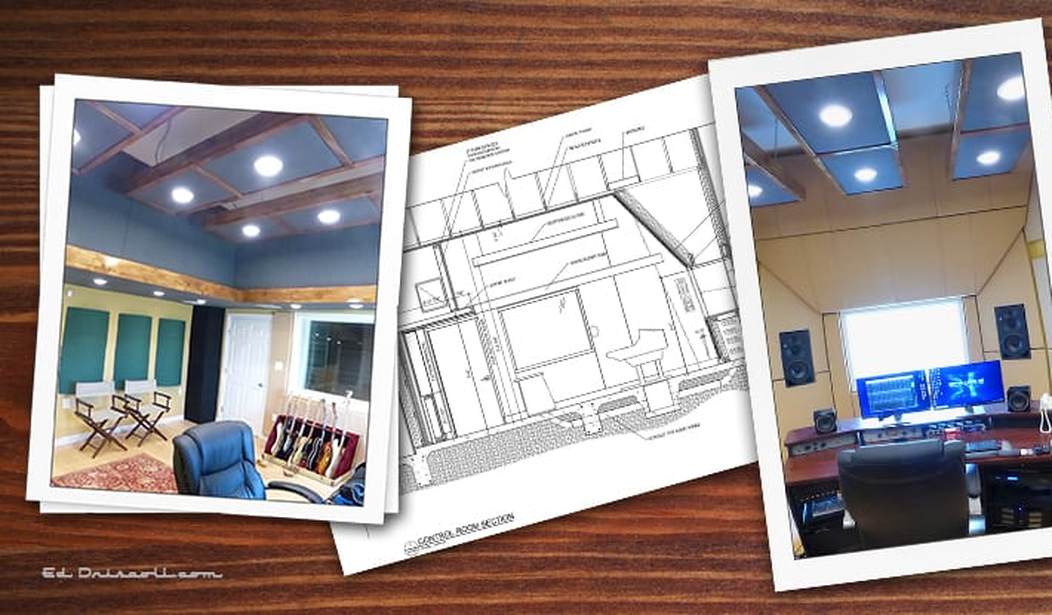

While directing Citizen Kane, Orson Welles famously said that a movie studio is “the greatest electric train set a boy ever had.” A music studio — even a home-based music studio — is a pretty nifty train set as well. We’ll explain all the stuff on the walls of these photos in copious detail in part two of this article, and how I built my project studio, but first some background on why I built it.

Back in the early 2000s, I wrote a review of PC-based recording software, which I dubbed “Abbey Road in a Box.” In retrospect, that obviously hyperbolic phrase was slightly disingenuous. It’s true that the various flavors of Digital Audio Workstation (or DAW) software are now so powerful that their ability to edit, process and manipulate sounds dwarfs what the Beatles and George Martin were capable of when they were recording Sgt. Pepper. However, that album still sounds timeless because of the Beatles’ and Martin’s sheer talent, the material they were writing and performing, and not least because the rooms in which they were recorded inside EMI’s Abbey Road Studios sound so good. A DAW, a PC, the right audio interface and appropriate ancillary gear can take you far, but they really need a good-sounding room to get the most out of them.

What makes a studio room sound good? That depends on what you want to record within it. So let me begin by explaining what I wanted mine for — and of equal importance, what I didn’t want to do in it.

The Album That Launched the Home Recording Revolution

As I’ve written before, I was fortunate to begin playing guitar in a rock band during a period when two music industry trends intersected. In 1983, Pete Townshend of The Who released the first “Scoop” anthology of his demo recordings. To promote the double album, Townshend gave a series of interviews in which he explained how, right from The Who’s earliest days, he “wrote” the band’s material by recording demos in his home studio, which he then passed around to the rest of the band, who built each song by first learning Townshend’s parts, and then embellishing them.

Townshend used largely expensive professional recording equipment in his home studios, but fortunately, around the time that Scoop appeared in record stores, the first affordable cassette-based four track recorders began appearing in music stores. These devices used conventional stereo cassettes, but played their tapes in only one direction, and had a recording head designed to allow for four individual tracks to be recorded. Thus it was now possible to put a drum machine on track one, a bass on track two, a guitar on track three, and a lead vocal and guitar solo on track four. The cassette tapes were hissy and had serious limitations, but it was now possible for any budding musician to record demos of his songs — to “write” a song onto tape by playing each part of a rock band.

By the mid-‘80s, inspired by Townshend’s example, and the burgeoning home music recording revolution, I “wrote” songs for my college-era South Jersey rock band, recording demos while home on the weekend, using a Roland TR-707 drum machine, a direct-injected Yamaha CX5M synthesizer, directed-injected Fender Precision Bass or its Yamaha synth equivalent, and a Scholz Rockman to input the electric guitar, all recorded into a Fostex 250 four-track cassette recorder in my parents’ basement. The only instrument recorded with a mic was usually my guide vocal, and fortunately, my shouting didn’t bleed through the ceiling when recording at 3:00 in the morning to wake up my parents.

Sadly, I ended up putting songwriting and recording on the backburner during the 1990s, when life and earning a living interceded. During that period, while I was sidelined, home music recording underwent a second revolution, arguably greater or with greater potential than what occurred during the previous decade. Recording on digital audio workstation software residing on a computer became both practical and affordable. And the prospect of unlimited tracks, using pre-recorded loops of real drums (played by talented real drummers) instead of a clunky sounding drum machine and infinitely easier editing and sound manipulation became increasingly exciting to me, and I yearned to get back into recording.

OK, Computer

As a result, when I resumed recording in 2000, now in my Northern California den, my method quickly became a bit more high-tech than my ‘80s approach: I used drum loops, synth bass or direct-injected my old band-era Fender bass, a variety of software synthesizers, and at first Line6’s Guitar Port USB interface, and starting in 2006, Roland’s VG-88 and the following year, Roland’s VG-99 guitar modeling processors. As in the ‘80s, the only instrument I recorded with a mic was usually my lead vocal, and fortunately, it didn’t bleed through the rest of the house when recording at 3:00 in the morning to wake up my wife. But just the loops of real drums alone improved the sound of my material, coupled with the quality of PC audio interfaces over the old hissy, warbly cassette tapes of the ‘80s.

Unfortunately, though, both in the 1980s and in the 2000s, I was recording and mixing in non-acoustically-treated rooms, which have serious limitations. Without careful preparation beforehand, lead vocals recorded on a high-end professional condenser mic in an untreated room typically sound pretty lousy because of how much room tone these sensitive mics pick up (until 2015, I used a much more forgiving Shure SM-58 dynamic mic designed for stage use — another Jurassic piece of kit from my college band era — and lived with the mid-fi sound quality). As advanced as electric guitar modeling has gotten, in most cases, it’s often tough to convincingly reproduce a steel-stringed acoustic guitar. When all the tracks have been laid down, mixes produced in a den or bedroom are very hit-or-miss as to how they’ll “translate” when played on a car stereo or ear buds. And cranking up anything but the smallest guitar amp risks annoying the wife and/or neighbors.

Gone to Texas

So in 2014, when we bought our house in Texas on 16 acres, I knew I wanted to build a studio that was separate from the house. The property originally included a 30-foot square steel shed, but it was uninsulated and had a dirt floor. So we decided to tear down the shed, and in its place, build a separate structure that would contain a two-car garage, a guest room and bathroom for visiting friends, and a dedicated, acoustically-treated studio (with about 320 square feet of space) and a 130-foot square isolation booth for me.

While Texas-based architect Ed Churchman designed the building that housed the studio, the studio itself was designed by veteran professional studio designer Wes Lachot. Wes is a very busy guy, and we couldn’t afford to employ him to fly out to oversee construction, so we back-stopped Joe Taylor, our general contractor with studio consultant Gavin Haverstick, and Bryan Pape, acoustical engineer of Atlanta’s GIK Acoustics, who helped to answer several questions about acoustic treatments.

Your humble narrator last summer; much drywall went into this project, as will be explained in part two. (Click to enlarge.)

After decades of recording demos, I had certain parameters in mind when I talked with Wes, and perhaps the most important is that I didn’t plan to record full drum kits. I was a frustrated drummer before playing guitar, and spent much of the 1980s programming my Roland TR-606 and TR-707 drum machines. Beginning in 2000, I’ve built up a healthy library of pre-recorded drum loops (and have gotten fairly adept at editing them and mashing them into new patterns), plus software synthesizer versions of most classic drum machines, and drum programs such as Addictive Drums. As I’ve known from the college-era band days when we recorded with a real drummer, trying to record a live drummer in a home studio can be extremely problematic. A drum set’s kick drum and an electric bass amp generate the most low frequencies in a rock group, and eliminating these from my studio’s recording goals helped greatly to define my room’s parameters and the acoustics it needed.

Thus, I wanted to limit the studio to loops and virtual drum machines, and limit live percussion to hand percussion such as tambourines, maracas, and cowbells. (As The Bruce Dickinson sagely advises, you always need more cowbell.) Also, I planned to record bass via software synthesizers such as Reason, the modeled Fender Bass sounds in my Roland VG-99, and record electric bass via direct injection, rather than record a live bass amp.

(Hey, I would have built studios to record full drum kits, not to mention hiring Ringo Starr and Mick Fleetwood to drop in for sessions, but my wife really balked when I discussed the cost of recreating EMI’s Abbey Road Studios in Texas.)

All of the foregoing led to my decisions about what I wanted in a project studio. All of which led into Wes’s plans, and the two rooms they launched. And that’s the subject of Part II of this article. Watch for it soon!

Update (3/29/17): The conclusion of this article can be found here, with many additional photos.

Update (February 17, 2018): Since the publication of this article, the studio’s desk was replaced with an Omnirax Force 32 dedicated recording studio desk. The photos in this article showing the original generic desk have been replaced.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member