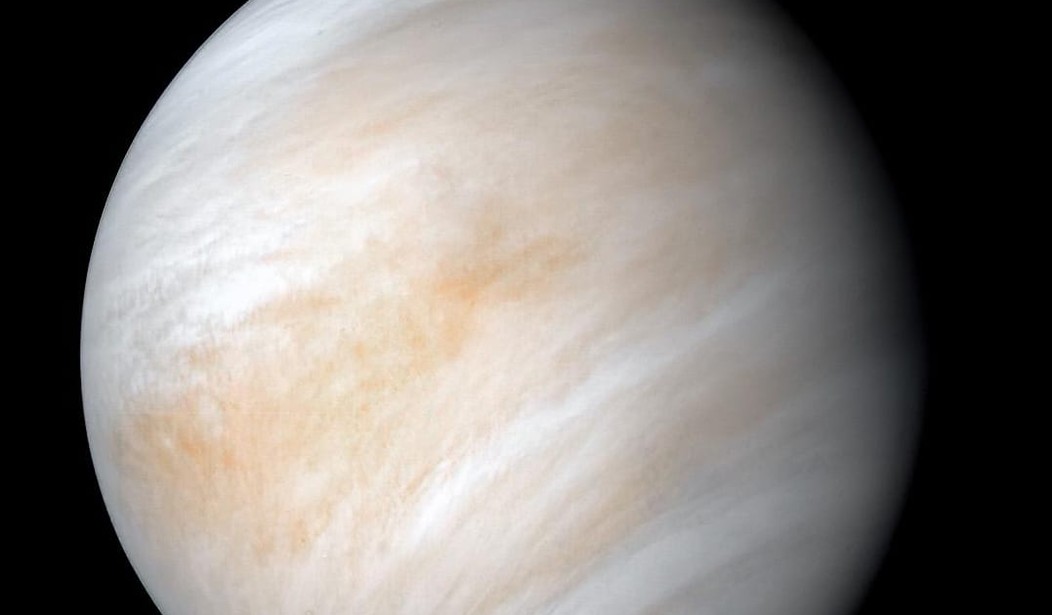

The planet Venus is a “hot mess.”

Venus may be the nearest to our own world but it’s not a place you’d likely want to visit. For one thing, you’d die very quickly.

While the planet is a tad smaller than the earth, so gravity ought to be roughly comparable on both worlds, its closeness to the Sun keeps the temperature high.

As in high enough to melt lead — nearly 900 degrees Fahrenheit.

The surface atmospheric pressure on Venus is about 100 times that of earth. Scuba divers know this is quickly fatal for humans, most of whom can only stand about a few times our earth’s atmospheric pressure unaided. That’s why we need submarines to get very far underwater.

At 100 times earth’s pressure, standing on Venus’ surface, we would be turned to goo. NASA doesn’t mince words:

You would not survive a visit to the surface of the planet – you couldn’t breathe the air, you would be crushed by the enormous weight of the atmosphere, and you would burn up in surface temperatures high enough to melt lead.

There is no liquid water or ice on the surface, the heat having a lot do with that. And it rotates backward compared to earth and the rest of the planets in our solar system. It’s covered by toxic cloud layers of carbon dioxide, which we cannot breathe, and sulfuric acid, which we definitely cannot breathe.

To find anything resembling earth-like pressure, light, and temperature on Venus, you have to go about 50 to 60 miles up into its atmosphere, past the devilish toxic sulfuric acid clouds and the stormy darkness and arid surface below.

So ok then, once the shutdowns are finally over, let’s not go there.

The hunt for life

Astronomers and exobiologists have long pinned the hopes of finding extraterrestrial life in our solar system not on Venus at all, but on either earth-like but cold Mars or Jovian moon Europa, which has liquid oceans under its 60-mile thick ice outer skin. Mars may have once had water oceans and rivers and it certainly had vulcanism. Its titanic Olympus Mons is the largest known volcano in the solar system. It’s three times the height of our Mount Everest and stretches out across an area roughly the size of the state of Arizona. Europa may have salty seas beneath the ice, and Jupiter’s gravitational tug may act as plate tectonics do on earth, stirring a creative churn. These two very different worlds have lately been our best hope for finding anything at all alive beyond earth yet in the neighborhood.

So it’s more than surprising that this week Venus has leaped to the head of the ET pack. No one saw that coming, including the scientists who suspect they’ve found it.

An international science investigation team working with two of the world’s most powerful telescopes say they have found the signature of the chemical phosphine in the Venusian atmosphere, right in that earth-like layer so many miles high above the planet’s hellish surface. Is it really there, and if so, how did it get there?

Phosphine is present on earth but it’s difficult to make. It’s also present in the atmospheres of gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, but the processes creating it there have nothing to do with life. On earth, phosphine is a signature of living processes and has come to be a signal the exoplanet hunters will look for. Might it be on Venus? The conditions there are wildly different from pretty much everywhere else we know.

The scientists who believe they have found its lines on spectra of Venus’ atmosphere are not saying it definitely is there or that life must be the reason for it. They just say they have seen its signature and have ruled out other known processes for making the garlicky gas.

In 2017 (English astronomer Jane) Greaves observed Venus with the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) on Mauna Kea in Hawaii, searching for bar code–like patterns of lines in the planet’s spectrum that would indicate the presence of different chemicals. While doing so, she noticed a line associated with phosphine. The data suggested the molecule was present at around 20 parts per billion in the planet’s atmosphere, a concentration between 1,000 and a million times greater than that in Earth’s atmosphere. “I was stunned,” Greaves says.

It’s always in the last place you look

Greaves and her team, including MIT molecular astrophysicist Clara Sousa-Silva, followed up observing Venus with the massive Atacama telescope in Chile. They found the telltale lines again, strengthening their initial finding from Mauna Kea.

Venus is our next-door neighbor. It’s a world that we not only can visit, we already have. The defunct Soviet Union and the United States began missions to reach Venus in 1961 and America succeeded in a fly-by of its atmosphere in 1962 (Mariner 2). The USSR and USA space race resulted in several successful missions to Venus, including the first sampling of its atmosphere, the USSR’s Venera 4 in 1967, America’s Mariner 5 fly-by a month later, a few more atmospheric missions, and then — touchdown. The Soviet Union’s Venera 8 landed on Venus on March 27, 1972. The United States had won the race to the moon four years earlier, so Venus was something of a consolation prize by then. The Soviets made Venus their world, orbiting and landing there several times before the Soviet Union’s collapse. No other nation has yet landed a spacecraft on Venus. Yellowish Venus is far less explored than our other neighbor, red Mars.

Venera 8 took measurements and examined its surroundings, but lasted less than an hour on Venus before it was crushed by the heavy atmosphere. It did tell us that Venus is hot and dry and a horrible place to try to live. Nothing discovered about Venus since then has fundamentally changed the game.

Extremism isn’t just for antifa

But life on Venus? That would change our view of Venus and a lot else. We have known for a while that “life as we know it” isn’t what we once thought it was. On earth, creatures have adapted to live in the most extreme circumstances. From boiling hot water spewing out of volcanic jets at the bottom of the ocean, to the thin, cold upper reaches of our atmosphere, we keep finding stuff alive. The discovery of “extremophiles” has expanded our understanding of the conditions that may foster life off of earth. The so-called Goldilocks Zone of habitable worlds and conditions may be wider than we expected, or ever even suspected.

It’s possible, though very unlikely, that one or more of the earth missions to Venus contaminated the atmosphere in some way and Greaves’ team is picking up evidence of that. It’s even possible that the origin of any life found there originated here. Meteorites have been known to thump Mars, sending up plumes of rocks that landed on earth later, and vice versa. It’s possible that something struck earth hard enough to put a piece of our world over on that one. The famous Allen Hills meteorite, which was once suspected of showing the traces of Martian life, is such a rock. It’s a piece of Mars sent to earth by a cataclysmic crash. We didn’t have to go Mars to look for life. Mars came to us.

This possible finding of the signature of phosphine above Venus doesn’t mean Venus harbored life in the past, as NASA suggested a year ago, or now. Though this finding is tantalizing and practically begs for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Marsophiles to send robotic explorers to traverse the surface of Venus.

Venus remains an unlikely world for life. Greaves’ team’s finding the signature of phosphine isn’t enough to change that yet. It will take a lot of peer review first, and follow-up observations then, and after that more missions to the planet next door.

“I’m confident our models and data reduction are good, but I’m still skeptical,” team member and molecular astrophysicist Clara Sousa-Silva told Scientific American. “I expect the world to come and point out the mistakes I’ve made.”

Skepticism is the way to bet until others replicate the finding. NASA will surely aim its big gun, the orbiting Hubble Space Telescope, at Venus again before long to check for phosphine. The itch to know what’s there and why must and will be scratched.

Bryan Preston is the author of Hubble’s Revelations: The Amazing Time Machine and Its Most Important Discoveries. He’s a former producer for the Hubble, a veteran, author, and Texan.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member