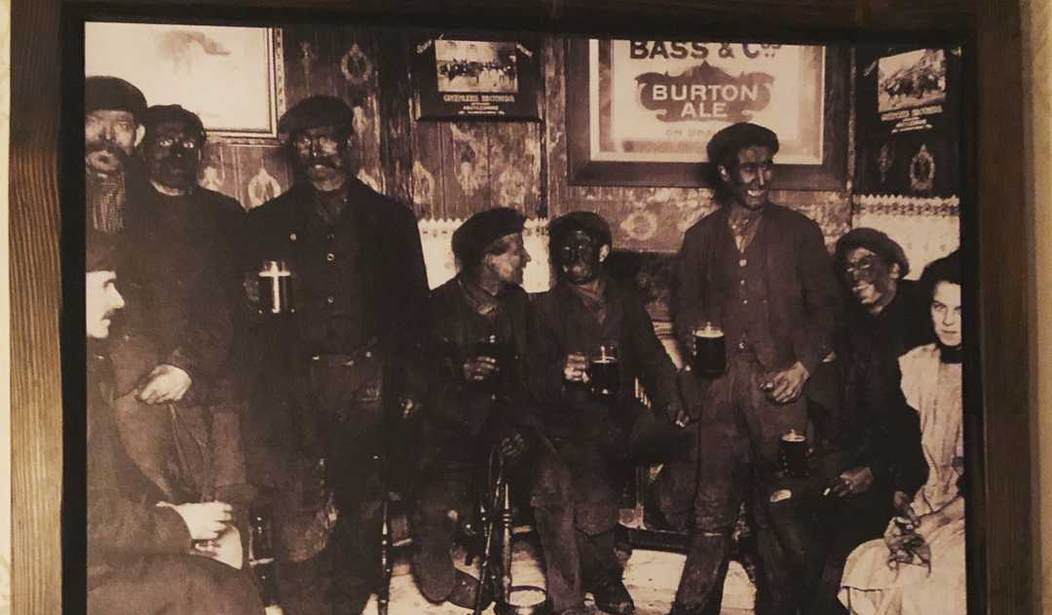

The other day, a Facebook friend shared a photo — and an article about the photo. The photo, a vintage item that looks as if it might date back as much as a hundred years, shows a group of white coal miners, their faces black with soot, standing at a bar, presumably at the end of a workday, and enjoying a round of beers together. The soot on their faces testifies to a long day of toil, in fact a lifetime of thankless, underpaid, backbreaking toil, far beneath the surface of the earth, which they performed in order to support their loved ones, some of them doubtless contracting respiratory ailments that shortened their lives.

Yet despite their hardship — a degree of hardship that is barely imaginable to most people living in the Western world nowadays — the expressions on the miners’ faces are cheerful. They’re enjoying their refreshments and one another’s company. They aren’t looking around for something to complain about. They’re making the most of this brief respite from their labors.

The photo, which hangs in a restaurant in downtown Phoenix, was reproduced on January 28 at AZ Central, the website of the Arizona Republic, that state’s largest newspaper. The accompanying article, by one Rashaad Thomas, was about his reaction to the photo, which he had noticed recently while attending a party at the restaurant.

Now, if you or I had been there and seen this photo, we might have regarded it as a small tribute to the quiet dedication of these men, as well as to other men like them, whose unsung labors contributed to the development of their nations’ economies. But Thomas, a black man, saw the picture differently. It made him angry — so angry that he spoke to one of the restaurant owners, a white man, and “explained to him why the photograph was offensive.”

To Thomas, you see, the men looked as if they were in blackface. It reminded him of the racist 1915 movie Birth of a Nation, “in which white actors appeared in blackface.” The restaurant owner, by contrast, “saw coal miners in the photograph. Therefore, it was not offensive.”

Well, yes, the owner saw coal miners. Because it’s a picture of coal miners. But to Thomas, this was irrelevant. “The context of the photograph is not the issue,” he asserts. “That photo tells me I’m not welcome.” To Thomas, “the photograph of men in blackface” (notice how these miners, grimy from a hard day’s work, are now “men in blackface,” as if they were deliberately out to insult black people) represented “a threat to me.” The soot on their faces, Thomas writes, “culturally says to me, ‘Whites Only.’ It says people like me are not welcome.” Thomas maintains that “the photograph should be taken down — sacrificing one image for the greater good.”

In other words, drop down the memory hole what may well be the only remaining image of some of those coal miners, the sole record of their lives of labor, in order to satisfy the sensitivities, reasonable or not, of one man who happened to be in that restaurant one evening for a party. (How many parties, one wonders, did those coal miners ever attend?)

At the end of his piece, Thomas admits that — surprise! — this wasn’t the only time he’d felt unwelcome in some public place. He explains that he’s often strolled into art galleries where he’s felt “not represented in the art.” (How many of those coal miners, one wonders, ever went gallery-hopping?)

Who, exactly, is Rashaad Thomas? I looked him up, and found some of his other writings. They’re entirely of an ilk with his rant about the photo. In August 2016, a website published a riff by him on “Strange Fruit,” the Billie Holiday song about lynching that was timely when Abel Meeropol wrote it in 1937, but that, as transformed by Thomas (his version begins: “Black bodies swing in the southern breeze / Children cut from stomachs hanging / Blood on the roots, blood on the leaves”), reads like a case of nostalgie de la bough. Elsewhere I found Thomas’ essay/poem “Policing Black Art,” which likens the treatment of “Black art” by cultural institutions to the deliberate killing of blacks by cops and the treatment of slaves at auction:

White institutions police and kill Black art like America polices and kills Black bodies … Naked Black canvases are forced onto white gallery auction blocks …

Here too, interestingly, the concept of blackface comes up, with Thomas complaining that white people to whom he’s submitted his writing have demanded that he “write and read in Black face.” He, in response, has “allowed them to take my art and tie it to a tree so that white folks in power can sculpt my art with their lashings.” (Note to Thomas: hey, that’s not a race thing; it’s everyday life as a freelance writer.) Thomas recalls an “elderly white man” who approached him after a poetry reading and said, “I understand why you are so angry. But, we are not all like that. I feel like I want to give you hug, but I don’t know how you will react.” Guess how Thomas characterizes this statement? As an act of “symbolic violence.”

With Thomas, then, if you’re white, you just can’t win.

In “Policing Black Art,” Thomas reverently cites Amiri Baraka, whose Black Arts Movement of the 1960s — with its pure hatred of “whitey,” fixation on violence, and utter indifference to aesthetic considerations — still lives in Thomas’s own work. In the movement’s defining work, a poem entitled “Black Art,” Baraka wrote:

“We want poems like fists beating niggers out of Jocks, or dagger poems in the slimy bellies of the owner-jews … We want poems that kill. Assassin poems, Poems that shoot guns. Poems that wrestle cops into alleys and take their weapons leaving them dead with tongues pulled out and sent to Ireland.”

Baraka’s record of intense racism, anti-Semitism, gay-hatred, and wife-beating culminated in a notorious post-9/11 poem in which he accused Jews of knowing beforehand about the terrorist attacks. It didn’t keep him from being named Poet Laureate of New Jersey a few months later.

In the same way, Rashaad Thomas’ pathological hostility toward caucasians hasn’t kept his career from chugging along just fine. He belongs to the Gutta’ Collective (“a group committed to sharing a Black and Brown narrative through art and poetry”), contributes to the blog of the University of Arizona Poetry Center, is co-curator of the “Poetry Spot” at the AZ Central website, and is Engagement Manager at the Phoenix Center for the Arts — a job that sounds like a plum gig. He’s even a clothing designer (Ra-harT Designs). From 2013 to 2017 he was at Arizona State University, studying nuclear physics — no, just kidding; he was a major in “Justice Studies” and “African/African American Studies.” (He has complained that, on his first spin around the campus, he didn’t see enough people who “looked like me.”) On Twitter, in recent months, he’s shared favorite quotes from the Koran, challenged white people’s alleged contempt for blacks (“If we are so inferior, why are you so afraid of us?”), and corrected the historical record about the Civil War (“Ya’ den’ been bamboozled Lincoln di’nt want to free no enslaved Black folx. He only wanted to save the Union”).

I don’t mean to single out Rashaad Thomas for criticism. He interests me because he is legion. He may, for all we know, have talent, but we may never know one way or the other, for his work is crippled by a conviction that he’s the object of acute, ubiquitous racial prejudice. He sees it everywhere. Indeed, he’s so intensely fixated on it that he constantly finds it even where it doesn’t even exist. This is a shame, because by all indications he is — compared to most people living on this planet today, and, even moreso, compared to most people who have lived at any time or place in human history — an extremely privileged soul. He resides in Arizona’s spectacular Sun Valley and makes a living by doing things that sound rewarding and, frankly, rather cushy. And yet his good fortune seems incapable of moderating his fury.

Among the few surprising moments in the writings of his that I’ve managed to locate are these two lines from “Policing Black Art”: “Who taught me to hate myself? / Who taught me to hate my own?” Amidst all the anger, the poignancy of these questions catches one unawares. One wants to answer him: You, like all too many other Americans in certain minority groups, have been taught to hate yourself not, as you may think, by bigotry against those groups, which has receded dramatically over the course of your lifetime, but by a poisonous ideology that has brainwashed you into seeing yourself almost exclusively in terms of a superficial personal attribute and into thinking that other people surely must see you that way as well. It has taught you to see meaningless slights as evidence of that prejudice, and to stew in what you have been encouraged to consider your own ineradicable victimhood. And it has rendered you virtually incapable of writing anything that isn’t a hysterical and aesthetically worthless response thereto.

And this is why your response to the photograph of those miners is so striking. Because whatever you may think, you’re far less of a victim than any of those miners, who, after a long day of grueling work, would have been more than justified to spend their few free moments grousing about their lives. One or more of them, for all we know, might well have agitated for better job conditions and higher wages. But even if they did, they don’t appear to have been in thrall to some toxic ideology of the sort that has consumed you with irrational rage. On the contrary, what we see in that picture is that on some unknown date in some unknown location, they chose to gather together and enjoy what leisure time they had. As the cameraman snapped their picture, they were all smiling, and when you look at them now, none of them, whatever their difficulties and frustrations may have been, looks remotely capable of taking offense at a picture on a wall.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member