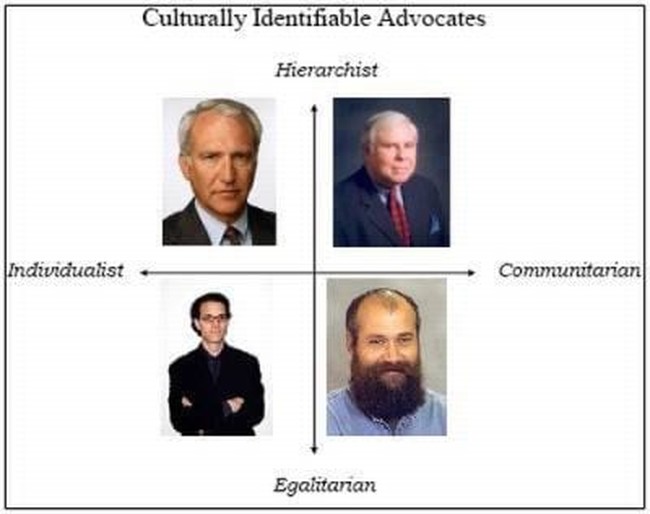

A person’s cultural and social worldview, as identified by the labels above, have more impact on determining their opinion on global warming than any other factor (Image reference - The Second National Risk and Culture Study, Yale Law School, 2007).

It has always been assumed that a lack of understanding of basic science and mathematics is the main reason the public can be so easily misled on controversial issues such as global warming. All that is needed, so science educators and campaigners believed, is a general increase in scientific literacy and people would come to more rational conclusions when presented with the facts.

But new findings published on Sunday in the journal Nature Climate Change by researchers taking part in the Cultural Cognition Project at Yale Law School shows that this is not the case at all. When faced with having to support one side or the other in important science debates, most people are influenced far more by their cultural and social worldviews than by solid science, no matter how well that science is presented. The public, especially those well-versed in science and mathematics, will usually agree with the side that comes closest to the values of the “tribe” they most identify with. In many cases, the facts don’t matter at all.

To examine the issue, Cultural Cognition Project researchers divide the population up as illustrated in the diagram at the top of the page.

Those identified as hierarchists believe that goods, responsibilities and rights should be distributed based on clearly defined and stable social status factors such as wealth and lineage. Egalitarians believe that distribution should be done equally, independent of such factors. Communitarians support the notion that society, usually government, should create circumstances so as to assure the flourishing of individuals in that society. Individualists believe that it is up to the individual to secure the conditions of their own advancement without the help or hindrance of government.

Those to the right of center on the political/philosophical spectrum tend to be more hierarchal and individualist than those on the left who tend towards egalitarian and communitarian worldviews.

Researchers found that egalitarians and communitarians consistently see global warming as posing a far greater risk to society than do hierarchists and individualists. There are several obvious reasons for this. Individualists disdain government interference in their lives, something that would increase under most plans designed to control climate. Communitarians accept collective action as a desirable route to solving such problems.

People who identify with a hierarchical, individualistic worldview perceive that a strong societal belief in dangerous human-caused global warming would result in restrictions on commerce and industry, activities they hold dear. In contrast, those of a more egalitarian, communitarian bent are generally suspicious of commerce and industry, which they believe promote social inequity. They want to impose restrictions on activities they naturally view as threatening to their worldview.

Previous studies by the Cultural Cognition Project are also of critical importance. They showed that people will accept or discredit identical information about global warming based on whether the resultant policy recommendations coincide with their social/cultural worldviews. For example, when presented with two articles promoting climate alarmism, articles that were identical aside from their policy prescriptions, the public’s trust in the validity of the articles depended on their worldview. If the solution to the supposed problem was taxation on greenhouse gas emissions, egalitarian-communitarians’ concerns about the risks of global warming rose while those of hierarchical-individualists fell. If the policy prescription was an expansion of nuclear power, egalitarian-communitarians felt the risk of global warming was significantly lower than in the first case, while hierarchical-individualists felt it was higher than they did previously.

This tells us that, to succeed, advocates must be prepared to offer policy prescriptions that appeal to their audience’s worldview. For example, climate realist advocates, those who promote the well-supported position that global climate changes all the time with little influence from human activity, can recommend policy prescriptions that include helping vulnerable people adapt to change to gain support from egalitarian-communitarians.

Public opinion about the threat posed by global warming is also heavily influenced by the perceived social/cultural worldview of the person presenting the information, other Cultural Cognition Project studies show. If advocates are seen to share worldviews with their audience, they have far greater success in swaying people to their point of view on controversial issues such as climate change. If advocates are perceived to hold worldviews that contradict those of the audience, the information being presented is much less believed. This is the case even if a hierarchical-individualist is presenting views normally associated with egalitarian-communitarians. The latter group are less supportive of egalitarian-communitarians’ views if they are promoted by an advocate from the opposite “tribe.” In fact, on some issues such as the intense and highly polarized debate over compulsory HPV virus vaccinations for 11-12 year old girls, audiences completely switched sides to one opposing their default position when the advocate presenting the information was on the other side of the social/cultural divide.

Other studies from the Yale Law School group have shown that even the public’s perception of who is, and who is not, an expert in climate science is heavily influenced by whether or not the expert’s worldview is perceived to coincide with that of the listener. Clearly, we need more advocates for the climate realist position who are seen to subscribe to an egalitarian-communitarian worldview.

Although there was a small decrease observed in the public’s overall concern about global warming as scientific literacy increases, the issue became increasingly polarized as literacy rose, the May 27 Nature Climate Change paper showed. In other words, skeptics become more skeptical and alarmists become more alarmist as they learn more about science and mathematics. Regardless, researchers found that the impact of cultural worldview was far greater than the impact of scientific literacy. What matters most, researchers find, is who is advocating the position being presented and how they are presenting it.

These findings will dishearten traditional science educators who for years have focused on disseminating clear and well-supported descriptions of the way nature works in the hopes that the public will come to more rational conclusions on issues such as global warming. It will also disappoint those who, because of their perceived political and philosophical positions, have little chance of swaying segments of the population who hold opposing worldviews. This does not imply that their work is not important, however. For example, many people with hierarchical-individualistic worldviews still support the climate scare and clearly these individuals must be the primary target audience for think tanks and other groups who hold strong free-market and other capitalist views.

The Cultural Cognition Project research findings reinforce the importance of the non-partisan, worldview-neutral strategy of groups such as the International Climate Science Coalition. Such an approach helps make it “safe” for people from across the social and cultural spectrum to work together without threatening anyone’s values. This is critical if we are to expand the tent of those who want to finally end the expensive and highly divisive climate debate in favor of rational climate and energy policy.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member