Tropical Storm Chantal, already moving west-northwestward at a lightning-fast clip, sped up further this morning, racing through the Lesser Antilles islands (where she reportedly caused modest damage) at a forward speed of 29 miles per hour. That’s roughly double the typical speed of a tropical cyclone in the deep tropics. Here’s a look at the storm’s low-level circulation on a Martinique radar loop this morning, courtesy of Eric Holthaus:

Chantal’s maximum sustained winds are now estimated at 65 mph, and her minimum central barometric pressure — after dropping to 1002 millibars overnight, then jumping back to 1010 mb — is at a still rather unimpressive 1006 mb.

The Dominican Republic, which Chantal is forecast to hit tomorrow, has issued a Hurricane Watch. However, as weatherblogger Levi Cowan (@TropicalTidbits) notes, it would be very difficult for Chantal to become a hurricane while moving at its current forward speed. Cowan explains that the strong trade winds which are pushing Chantal rapidly to the WNW are also “taking [the storm’s] feet out from under her,” creating “random” or “unstructured” convection (thunderstorm) patterns that are unable to wrap into a coherent mid-level circulation. Joe Bastardi writes that the low-level center, seen in the radar loop above, is “probably not aligned with [the] mid level” circulation.

In a just-published update, Dr. Jeff Masters writes:

Chantal’s winds are unusually high considering the storm’s high central pressure of 1006 mb and disorganized appearance on satellite imagery. Chantal is fighting dry air associated with the Saharan Air Layer (SAL), as seen on water vapor satellite loops. This dry air is creating strong thunderstorm downdrafts that are robbing Chantal of moisture and energy. Visible satellite loops show the outflow boundaries of these thunderstorm downdrafts at the surface, spreading to the northwest of Chantal. Martinique Radar shows a large area of heavy rain that is not well-organized, lying mostly to the west of the Lesser Antilles Islands.

Dr. Masters adds that “a tremendous amount of wind shear” is occurring, which “make[s] it very difficult for a tropical storm to keep the surface center aligned with the upper level center.” He also notes that conflicting measurements from balloon soundings near the storm today “demonstrate[] that there is a lot going on the atmosphere at small scales we cannot see which makes intensity forecasting of tropical cyclones very challenging.”

What next? Analytically, not much has changed since yesterday. The key question remains whether Chantal will survive its forthcoming passage over Hispaniola. (That’s assuming the track doesn’t shift; Cowan notes that some computer models are taking the storm’s center more toward eastern Cuba.) Again quoting Cowan, it’s “hard to draw conclusions about post-Hispaniola until Chantal is actually past Hispaniola.” That’s because “Hispaniola can destroy storms,” but re-strengthening seems a reasonable possibility if the circulation can survive its interaction with those high mountains.

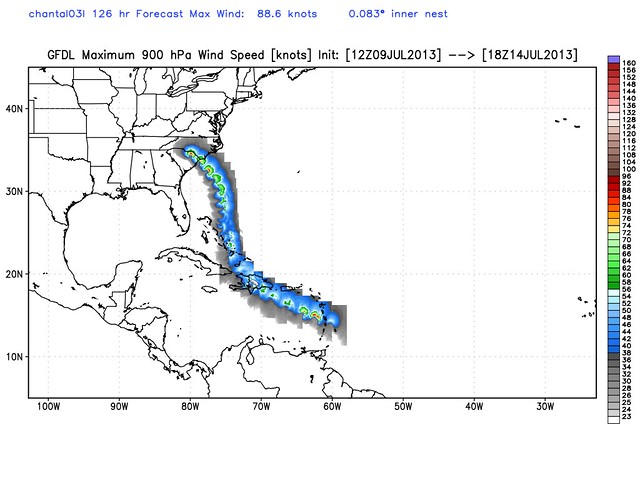

Even if Chantal does survive Hispaniola and then re-strengthen, there isn’t any particular reason to believe it will become a monster. Meteorologist Ryan Maue points to one scenario favored by the latest run of the GFDL computer models, which shows a restrengthened-but-still-weak Chantal hitting the Carolinas this weekend, as a “likely tropical storm — main threat would be rain”:

CAUTION: That’s just one computer model forecast, 126 hours out, so don’t focus on the details of the track — they’re not remotely reliable at this point. (Myrtle Beach is in no more specific danger right now than anywhere else along the east coast of Florida, Georgia or the Carolinas.) Instead, focus on the general pattern: storm hits Hispaniola, weakens, turns right, moves through the Bahamas, turns back left and re-strengthens. That’s generally what we can expect, if Chantal survives Hispaniola.

Meanwhile, by the time Chantal is potentially impacting the Southeast, we could be looking at Tropical Storm Dorian following in her footsteps. Dr. Maue, posting an image of four recent computer-model forecasts for Sunday evening, tweets:

Last 4-GFS forecasts confused about #Chantal, but consistent on developing next tropical storm in far Atlantic: pic.twitter.com/gaPBelquFl

— Ryan Maue (@RyanMaue) July 9, 2013

And “Dorian,” if it comes, could be just the beginning. Historically, Chantal looks like a harbinger of an active season to come. In Cowan‘s words: “If you weren’t prepared for this season, this ought to wake you up. Active Julys usually mean active Aug-Sep too. GFS supporting our ideas.” Meteorologist Michael Watkins tweets: “My [calculations] show since 1952 – seasons w/ July development in the deep tropics run approx 150% of average ACE [Accumulated Cyclone Energy] – vs 85% w/out.” He adds that such seasons “have a 75% chance of seeing ACE >120 for the season.” An ACE above 103 is considered an “above normal” season, and an ACE above 120 would be in the ballpark of the 2011 season (126), most memorable for Hurricane Irene, and the 2012 season (133), most memorable for Isaac and Sandy.

Dr. Jeff Masters elaborated yesterday on the Chantal-as-harbinger theme:

Chantal’s formation on July 8 is an usually early date for formation of the season’s third storm, which usually occurs on August 13. A large number of early-season named storms is not necessarily a harbinger of an active season, unless one or more of these storms form in the deep tropics, south of 23.5°N. According to Phil Klotzbach and Bill Gray, leaders of Colorado State’s seasonal hurricane forecasting team,

“Most years do not have named storm formations in June and July in the tropical Atlantic (south of 23.5°N); however, if tropical formations do occur, it indicates that a very active hurricane season is likely. For example, the seven years with the most named storm days in the deep tropics in June and July (since 1949) are 1966, 1969, 1995, 1996, 1998, 2005, and 2008. All seven of these seasons were very active. When storms form in the deep tropics in the early part of the hurricane season, it indicates that conditions are already very favorable for TC development. In general, the start of the hurricane season is restricted by thermodynamics (warm SSTs, unstable lapse rates), and therefore deep tropical activity early in the hurricane season implies that the thermodynamics are already quite favorable for tropical cyclone (TC) development.”

Two of this season’s three storms have formed in the deep tropics–Tropical Storm Barry, which formed in the Gulf of Mexico’s Bay of Campeche at a latitude of 19.6°N, and now Tropical Storm Chantal, which formed at a latitude of 9.8°N. With recent runs of the GFS model predicting formation of yet another tropical storm southwest of the Cape Verde Islands early next week, it appears that the Atlantic is primed for an active hurricane season in 2013.

Stay tuned to Weather Nerd for updates on Chantal and any other storms that may threaten the United States. For even more frequent updates, follow me on Twitter (@brendanloy). Another good resource for the latest information is Amy Sweezey’s “Wx Tweeps” Twitter list.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member