As Michael Anton writes in City Journal, while Tom Wolfe will forever be as associated with New York as Dickens is with London, he’s also spent a fair amount of time documenting the status seeking, lust to start from zero, and ambient weirdness of California as well. Not the least of which including…:

Wolfe’s next book after Acid Test was the great tour de force Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers (1970). The titular radicals were the Black Panthers, founded in Oakland, California, four years earlier. That this anti-American group was welcomed into the bosom of the American establishment that it wanted to destroy was naturally treated by Wolfe as a farcical fad.

Wolfe’s friend Harvey Mansfield once remarked that you haven’t understood any paragraph in Machiavelli until you have found something funny in it. It’s unnecessary to look for the comedy in Wolfe; it will find you, quickly, and never let up. However, you haven’t understood any passage in Wolfe until you have found the seriousness beneath the surface. In the course of his research, Wolfe discovered that the Black Panther Party’s vaunted “ten-point program” had been drawn up in the North Oakland Poverty Center—that is, in an office established, operated, and funded by the government. These offices, he wrote later, constituted “official invitations from the government to people in the slums to improve their lot by rising up and rebelling against the establishment, including the government itself.” The comedic action of Mau-Mauing—tough-looking, angry-sounding ghetto warriors marching to downtown San Francisco to scare the bejesus out of a hapless white civil-service lifer so that he’d award their group a grant from the poverty program—would soon be institutionalized through the infamous Acorn and similar organizations. The rebels became a kind of parallel establishment and, eventually, the establishment itself.

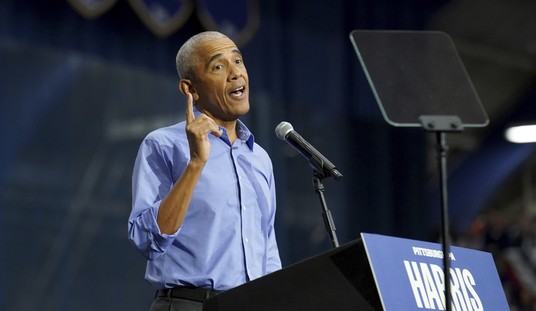

I inform Wolfe that, as far as my research has discovered, Mau-Mauing contains the first publicly printed appearance of the now-ubiquitous term “community organizing.” (It occurs twice, in fact.) “Really?” he says. “I didn’t realize that.” Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals, the profession’s manifesto, was published one year later. It’s common, for someone charged with introducing Wolfe to a public gathering, to note how often he predicts coming headlines. Three months after the publication of The Bonfire of the Vanities, for example, the Tawana Brawley case exploded. Such feats of reportage are so routine for Wolfe that we have come to expect them. But it’s hard to see how he can ever top having explained the rise of Barack Obama when the future president was only nine years old.

Heh. Read the whole thing.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member