There is a story based on an African’s experience in America. It is one of personal success and it is one that should wake us up to the opportunities our young people are missing. Not because the opportunities aren’t there, but because attitudes are misdirected. Because parental guidance is lacking. In some ways this is a difficult story to tell because it speaks to a number of truths.

The story is about a young man, Chinedu Ezeamuzie, 21. Originally from Nigeria, he’s lived most of his life in Kuwait. In 2003, his parents brought him and his three siblings to America, where he was enrolled at the Clarke Central High School in Athens, Georgia, his first time in a public school. He came from a mother and father that instilled values of family, community, spirituality, and self-betterment.

On his first day in school, wearing khakis, a button-down dress shirt, and nice leather shoes, this African caught the attention of the African-Americans in the school cafeteria. They ridiculed him. He said, “They gave me ‘the look,’” and asked in so many words, “Why is this guy dressed like the white folks, like the preppy guys?”

He would be insulted because he ate in the school cafeteria with whites. The blacks accused him of being a “traitor.” Such attitudes made no sense to Ezeamuzie. In Kuwait, his life was enriched in time spent with Europeans, Arabs, workers from the Philippines, and a mixture of groups from the African continent. The thinking was so puny, narrow, and counterproductive that it was hard to believe it was coming from Americans.

Ezeamuzie didn’t understand why so few black students were in his advanced placement classes. He would find it was in part because of peer pressure not to excel, not to be “different.” In time, he relaxed his British-trained tongue, but the more he tried to fit in, the more confused he became. He wondered: Why did they mock students for being intelligent? Why did every conversation seem to go no further than drugs, girls, and materialism?

The experience caused him to reflect on the stereotypes Americans, including African-Americans, have of Africans. No, he didn’t run with tigers, climb trees, or chase monkeys. He had to overcome stereotypes of African-Americans. No, they aren’t all rappers, gang-bangers, and criminals on the run. But it hurt him to see in his life at school that so many were apathetic about the value of an education. As much as he wanted to blend in, he couldn’t help but stand out. Eventually, he faced the fact that he was different and needed to stay that way for the sake of his future.

The young man is now a graduate from Georgia Tech, having majored in marketing. He’s even been running his own web development company for several years. He balances his professional side with his musical side as a singer/songwriter who performs for fun at the college.

The story I read quoted another Nigerian student living in Baltimore, Maryland, named Vera Ezimora. She said, “We have all been tortured.” But she noted that holding on and reliving the past did nothing but add to the torture, referring to the history of racism and slavery. To know the history is good. To dwell on it is not.

The experience of the Nigerian in Georgia is one any number of teachers have witnessed and some readers have lived through. Young people who’ve learned too early how to be cliquish. Who laugh at intelligence and behave as though ignorance is bliss. Who ridicule the student who forgoes play to study and doesn’t raise an eyebrow when a friend ditches class or drops out of school. Who has no sense of connection between where he or she is now and where they may want to be — or where they’ll wind up at this rate.

I recall a conversation I had with a fellow named Patrick, originally from the Congo. He told me if a kid goofed off in class, he was whipped. When word got back to the home, he was whipped again. Sometimes he was that kid. In the words of a saying from World War II, the attention he received caused him to “straighten up and fly right.” Apply that discipline in most American communities today and a call would go out to Child Protective Services.

Where did this attitude, which has been around for decades, come from that elevates acting foolishly over building a strong and productive future? An attitude that ultimately knows no ethnic distinction? I ask that question rhetorically as any of us can come up with our own answers.

Bill Cosby has made a second career beyond the bounds of comedy to comment on black attitudes towards education. He organizes his own town halls challenging inner-city leaders and families to get serious about education. In a talk given on the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court case that knocked down segregation in the public schools, Cosby hit a nerve: “People marched and were hit in the face with rocks to get an education, and now these knuckleheads are walking around. … The lower economic people are not holding up their end of the deal. These people are not parenting.”

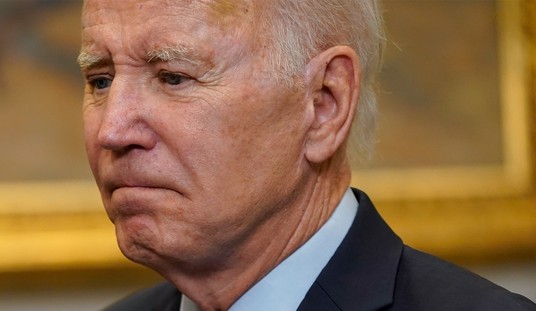

Whatever else one thinks of President Barack Obama, politics aside, his election is a way for making education, intellect, and personal drive “cool.” Echoing the tough-love talk of Bill Cosby, President Obama has said the time for excuses is over. When you have homework to do, turn off the TV and do it. If you see someone breaking windows, call the police and lock them up. Parents, you have an obligation to communicate with your children’s school, to attend the parent-teacher meetings, and to drive the agenda of your children’s education. It’s too important to leave education to the educators.

That’s what was taught in Chinedu Ezeamuzie’s family. That used to be what we taught here.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member