TEL AVIV – After living in an Arab country for nearly six months, arriving in Israel came like a shock.

It startled me from the air. Whoa, I thought, as I looked out the window of the plane over the suburbs of Tel Aviv. If the border were open I could drive down there in a short couple of hours from my Beirut apartment. But this place looked nothing like Lebanon. My Lebanese friend Hassan calls Israel Disneyland. I thought about that and laughed when I watched it roll by from above.

Trim houses sprawled in Western-style suburban rows like white versions of little green Monopoly board pieces. Red-tiled roofs somehow looked more Southern California than Mediterranean. Swimming pools sparkled in sunlight. I felt that I had been whisked to the other side of the planet in no time.

The airport shocked me as well, although it probably wouldn’t shock you. There were more straight lines and right angles than I was used to. There were more women, children, and families around than I had seen for some time. Obvious tourists from places like suburban Kansas City were everywhere.

Arab countries have a certain feel. They’re masculine, relaxed, worn around the edges, and slightly shady in a Sicilian mobster sort of way. Arabs are wonderfully and disarmingly charming. Israel felt brisk, modern, shiny, and confident. It looked rich, powerful, and explicitly Jewish. I knew I had been away from home a long time when being around Arabs and Muslims felt comfortably normal and Jews seemed exotic.

First impression are just that, though. They tend to be crazily out of whack and subject to almost instant revision. Israel, I would soon find out, is a lot more like the Arab and Muslim countries than it appears at first glance. It’s not at all a little fragment of the West that is somehow weirdly displaced and on the wrong continent. It’s Middle Eastern to the core, and it has more in common with Lebanon than anywhere else I have been. The politics and the history are different, of course. But once I got settled in Tel Aviv I didn’t feel like I had ventured far from Beirut at all.

Lisa Goldman kindly welcomed me to the country and met me for drinks in a dark, smoky, and slightly bohemian bar on my first night. We talked, as everyone does, about The Conflict.

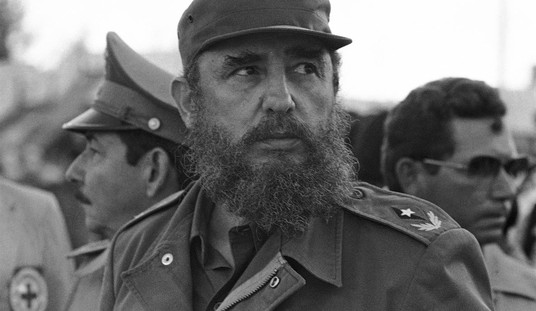

Because I’m an idiot who can’t remember to take enough pictures of people, I pulled this one of Lisa off her own Web site.

Lisa is a journalist who has been writing for the Guardian lately. She moved from Canada to Israel years ago when Ehud Barak was prime minister. Peace between Israelis and Palestinians looked imminent. Israel was on the threshold – finally – of becoming an accepted and normal country in the Middle East. It was the perfect time to relocate, a time of optimism and hope. A cruel three weeks later that dream was violently put to its death. The second intifada exploded. Israel was at war.

“It was so traumatizing,” she said. “And everybody blamed us. I don’t think I will ever get over it.”

Last year she wrote a six-part series on her blog called How Lisa Came to Israel. It’s riveting and terrifying to read. She must turn that material into a book. Do yourself a favor. Set aside some time and read Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four, Part Five, and Part Six. If you’re a literary agent, send her an email.

“I was near 11 or 12 suicide attacks during the intifada,” she said. “But that’s nothing. I know people in Jerusalem who were near 40 or 50.”

She kept going to restaurants, cafes, and bars even while bombs exploded somewhere almost every day. She even chose to sit right next to the front windows, the least safe place in any establishment.

“The staff kept asking me if I was sure I wanted to sit there,” she said. “I did.”

“I didn’t want to visit Israel then,” I said.

“Hardly anyone did,” she said. “The thing is, though, even when the intifada was at its peak you were far more likely to be killed in a traffic accident than by the bombers.”

She’s right about that. Most supposedly dangerous countries in the Middle East are considerably safer than they appear from far away. The region is not one never-ending explosion. Even so, suicide bomb operations are far more terrifying and traumatizing than car crashes. They’re murderous. They’re malevolent. They’re on purpose.

“It’s especially disturbing when you know what those bombs do to the human body,” she said.

“Do I want to know?” I said. I was not sure I did.

She shrugged and raised her eyebrows.

“Okay,” I said. “Just tell me.”

“Arms and legs go flying in every direction,” she said. “Heads pop off like champagne corks. You just can’t believe anyone hates you that much.”

*

Sometimes the Middle East feels like it’s drowning in bigotry, hate, and stupidity. But hate is not the only human emotion in that part of the world, even between Arabs and Jews.

Lisa is a liberal. Not the Bush-hating idiot variety, but the kind of brave person who continues to believe in the world no matter what kind of hell it throws at her. She spends a lot of time in the West Bank and Gaza even though the people who live in those places just replaced Yasser Arafat’s Fatah regime with Hamas.

“I have Palestinian friends who say things I don’t like at all,” she said. “They say they want to destroy Israel, that it has no right to exist.”

“How can you be friends with people like that?” I said.

“Because I know the difference between rhetoric and reality,” she said.

“Threats from the West Bank aren’t just rhetoric,” I said. “How many suicide bombings did you say you’ve seen?”

“These people will never hurt me,” she said. “They are my friends. They love me. And when I say love, I do not mean that lightly.”

I thought about that, and I thought about why someone might want to reach out and forge such seemingly-impossible friendships with people who declare themselves enemies. There’s a lot more behind it than a yearning for peace and the standard liberal can’t-we-all-just-get-along point of view. It strikes me, partly, as an emotional survival technique. I, for one, would not be able to tolerate living in Israel if I did not have Palestinian friends who could balance out the restless hate from some of the others. (I’d also like to have them as friends for the usual reasons, of course.)

“How can they be friends with you?” I said.

“That’s the real question, isn’t it?” she said.

I hadn’t been in Israel for even one day and I already knew I would leave with more questions than I had when I got there. I think I understand Lisa, though she might disagree. I don’t even think I understand her Palestinian friends. (I did not get a chance to meet them. I have work to do when I go back.)

“Hamas propaganda requires dehumanization,” she said. “When you meet someone face to face you become a real person. Then they can’t hurt you.”

But some of them can. The worst of them do. It takes a special kind of moral, emotional, and physical bravery to venture regularly into the West Bank and Gaza – as an Israeli civilian – and forge meaningful lasting friendships with people who say they want to destroy you. Lisa does it. I like to think I would, too, if I were Israeli. But I honestly don’t know if I could, not if I lived through the terror and rage of the intifada as she did. That’s one reason I wanted to meet her.

One of the most common spray-painted slogans in Tel Aviv says Know Hope. I don’t know who wrote it or why. Does it even matter? Israel is a stressful angst-inducing place. Not compared with Baghdad, for sure, but definitely compared with Egypt, Lebanon, and Northern Iraq. I felt better every time I saw it painted on walls. Know Hope. Those two simple words are so much more poignant in a place like Israel where the current (relative) lack of violence is almost certainly only a lull. Actual peace is well on the other side of the horizon.

Hope is precious and hard in Israel now. Hamas is taking over the reins of power in Palestine. The old Fatah regime was hideously corrupt and destructive. Some Palestinians, I am sure, voted for Hamas as a protest against Arafatism. Even so, terrorists officially rule the West Bank and Gaza with the consent of the governed.

And yet – and yet – the Israelis voted in a center-left government as a response. For a while there Israel wanted a man in power who was just a big fist. Until the second intifada broke out, Ariel Sharon – the Butcher of Beirut – was considered marginal and extreme by Israelis as well as by almost everyone else in the world. Yet they swung hard to the right and picked him to lead.

I wouldn’t say Israel has since swung hard to the left. But the Labor Party did receive one and a half times as many votes as Likud in the general election last month. Wielding a big fist no longer seems necessary whether it actually was in the first place or not. The intifada is more or less over. Brutal Israeli crackdowns in the territories are likewise more or less over. That may not be enough to feel hope, but it’s something.

Seeing Israel and Palestine for myself as they really are makes me slightly more hopeful than I was before I got there. The standard narrative of the conflict is a cartoon. Upon closer inspection, it’s a lot more complicated. And it’s a lot more interesting, too.

It may look like a never-ending and unresolvable death struggle with Arabs and Palestinians on one side, Israelis and Jews on the other. But people like Lisa and her Palestinian friends can’t be crudely reduced to that level. And we’re talking here about Palestinians who say they do want to destroy Israel, not just the liberals and the moderates who say they don’t.

Then there are those – and they’re almost completely ignored by the media – who defy these categories completely.

The Druze serve in the Israeli Defense Forces. And the Druze are as Arab as anyone else in the region. The biggest problem the Israeli government has with Druze members of the IDF is not that they are not loyal. The biggest problem is that they are consistently the most roguish and brutal toward Palestinians. They speak Arabic as their first language. Palestinians say they are traitors.

Bedouin also serve in the Israeli Defense Forces. The skills they learn as desert wanderers make them the perfect trackers.

Don’t assume the only reason Bedouin work with the Israelis is because they are loyal to the state they happen to live in, as may (or may not) be the case with the Druze. The tight relationship between Israeli Jews and Bedouin Arabs crosses international borders.

Lisa told me the Bedouin in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula speak Hebrew.

“Why?” I said. “Did they learn it during the occupation?” Israel seized the Sinai from Egypt during the Six Day War in 1967 and gave it back when Anwar Sadat agreed to a peace treaty.

“No,” she said. “They wanted to learn Hebrew so they can talk to us when we go down and visit.”

“When you go down there and visit?” I did not know what she was talking about.

“Last year 200,000 Israelis visited the Bedouin during Passover,” she said.

“Two hundred thousand,” I said. “On just one day?”

“You didn’t know about this?” she said.

“No,” I said. Before I went to the Middle East I had no idea Israeli Jews had any kind of genuinely friendly relations with Arabs in any country except right-wing Lebanese Maronites. And a significant number of Maronites say they aren’t even Arabs at all.

“The Bedouin roll our joints for us,” she said. “They sell us hashish. Israeli women like to go topless.”

“You go topless in front of the Bedouin?” I said. “Isn’t that offensive?” Bedouin are arguably the most conservative people in the entire Middle East.

“It doesn’t bother them,” she said. “They understand that our cultures are different. They don’t impose their values on us. And I never once saw a Bedouin man with wandering eyes.”

It made sense once I thought about it. Bedouin may be Egyptian Arabs, but they are completely isolated from Hosni Mubarak’s deranged state-run media. They could not care less about the politics of the so-called Arab-Israeli conflict. No one ever told them they are supposed to hate Jews. When politics can be pitched over the side, Israeli Jews and at least some Arab Muslims have a natural affinity for one another and they get along great.

“They are our brothers,” she said.

Post-script: Please help support non-corporate writing. I’d like to do a lot more traveling and writing in the future, and your donations today make tomorrow’s dispatches possible. Thanks so much for your help so far.

[paypal_tipjar /]

“You Just Can’t Believe Anyone Hates You That Much”

Advertisement

Join the conversation as a VIP Member