IN A MINE, BY HAND: Guess How Federal Retirements Are Processed.

April 9, 2025

MANAGING THE REQUESTS FOR MEETINGS WITH OTHER COUNTRIES IS PROVING A CHALLENGE: There’s an Update on Tariff Negotiations.

SOMETHING NEEDS TO BE DONE ABOUT THESE DEMS EXPOSING THEMSELVES: MSNBC Guest Totally Implodes Over Trump’s Immigration Policy, But Exposed Something Hilarious.

APPARENTLY HE’LL HAVE TO CHARGE SOME SUPREME COURT JUSTICES, TOO: Yeah, About Those Contempt Hearings Boasberg Was Mulling for Trump Officials…

I’M OLD ENOUGH TO KNOW THE LEFT HAS ALWAYS BEEN MURDEROUS. THEY JUST USED TO BE QUIETER ABOUT IT: Stunning New Study Shows Left’s ‘Assassination Culture’ Has Hit Disturbing Levels – Trump and Musk Targeted.

I HAVE NOTED THAT SOCIALISM MAKES EVERYTHING GREY: Is Color Being Drained from the World?

Let’s reverse that.

THIS IS THE MOST META DISGRACEFUL EVENT EVER: German journalist sentenced to seven months of probation for a Twitter meme poking fun at the Interior Minister’s lack of commitment to free speech3

CAN GREAT BRITAIN SURVIVE THE PRESENT? I DON’T KNOW. AND IT MAKES ME SAD: This British woman should not be in jail.

OH, CALIFORNIA, NEVER CHANGE: This is one of those stories that could only happen in California.

AND FOR THE X-LESS: Here.

WELL, HE IS (WAS?) AN HONEST POLITICIAN. HE STAYED BOUGHT: Report: Biden Admin Hid Report Linking American COVID Cases to China’s Military Games in October 2019.

THE LEFT’S OUTRAGE IS HIGHLY SELECTIVE: Where is the outrage now?

April 8, 2025

WASHPOST FAWNS OVER FINAL SEASON OF HANDMAID’S TALE, DUCKS MOSS’S SCIENTOLOGY: We quoted Mark Judge in the last hour, who wrote, “Jeff Bezos is trying to save The Washington Post, which is losing hundreds of millions of dollars a year and has lost all credibility.” Bezos’ spring clean of the Augean Stables is, alas, going quite slowly. At NewsBusters, Curtis Houck writes:

In a huge, five-page, 3,200-word spread in Sunday’s Washington Post, Style section writer Jada Yuan heaped more liberal bile on the grossly anti-Christian, anti-family, pro-baby death, and far-left crowd behind the show The Handmaid’s Tale ahead of its final season. As is usually the case with puff pieces on the show, Yuan left out that star Elizabeth Moss is a devout Scientology which, if there ever was a dangerous cult, that’s it.

“‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ is ready for its revolution; The dystopian TV drama is winding up for its big finish. Its cast members have lots to say about its relevance,” Yuan beamed in the online headline.

Despite women still having been allowed to protest en masse and abortions continuing to take place across the country, Yuan fed the narrative women* have almost become lifeless, listless vessels for the patriarchy in the Trump presidencies.

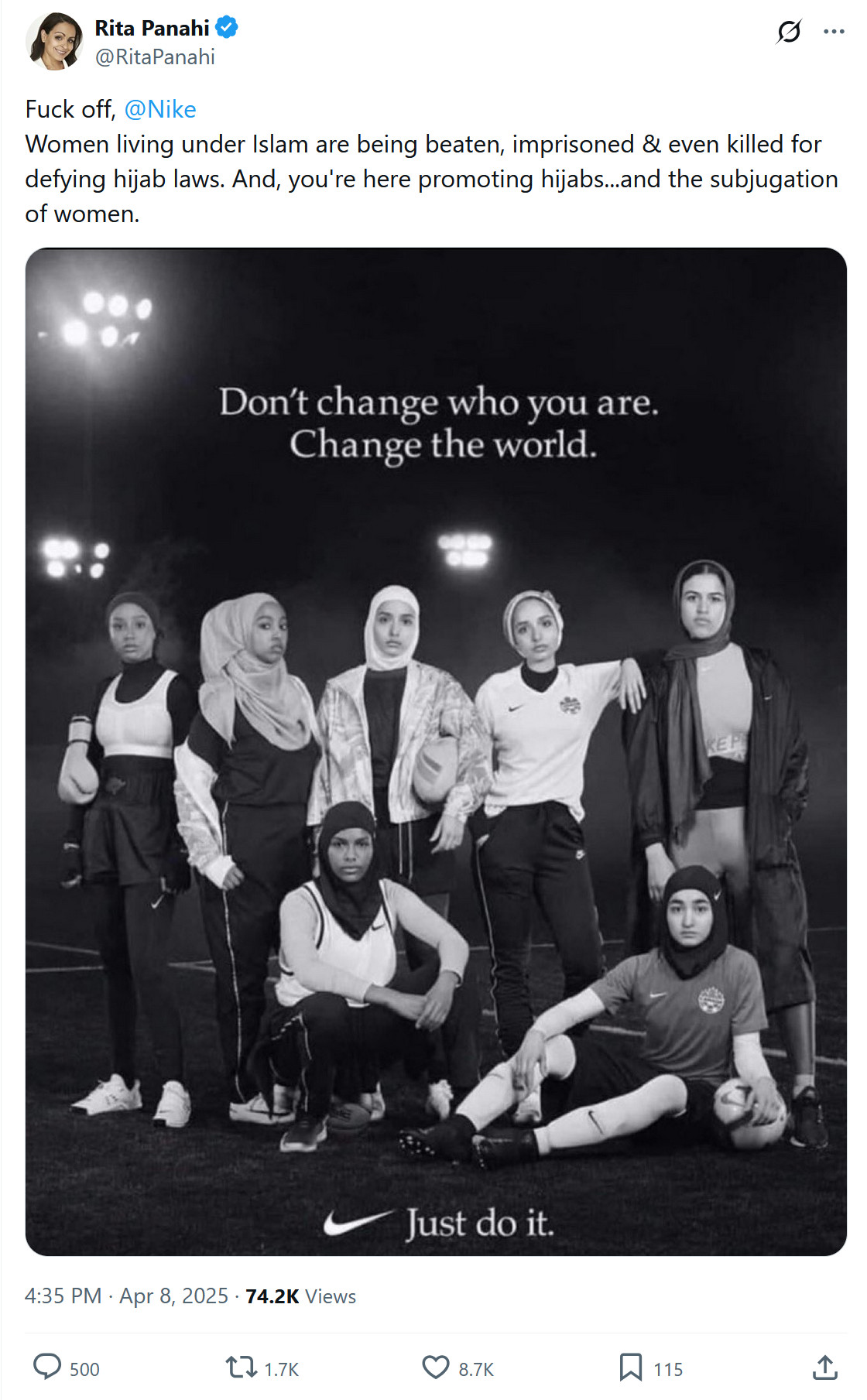

The image that accompanies Houck’s post is doubly ironic:

Everybody’s masked up, which is what the left demanded of all of America in 2020, they’re all wearing outfits that seem much like jilbabs. But many leftists have long defended the jilbab; or as Phyllis Chesler wrote in 2009, paraphrasing the opinion of a pre-Trump supporting Naomi Wolf: The Burqa: Ultimate Feminist Choice?

* But what is a woman? Flashback to 2021: The author of The Handmaid’s Tale tweeted a column defending the word ‘woman’ and the woke are outraged.

UPDATE: As I was saying:

OPEN THREAD: Blogging on a groovy Tuesday.

AMERICA’S NEWSPAPER OF RECORD:

Touching: Amy Coney Barrett Adopts MS-13 Gang Member https://t.co/e6NavId0D0 pic.twitter.com/PPugCUcZOB

— The Babylon Bee (@TheBabylonBee) April 8, 2025

SO COMMON IT’S NOT NEWS ANYMORE, BUT THAT’S NEWSWORTHY ON ITS OWN: SpaceX launches 27 Starlink satellites on brand-new Falcon 9 rocket, aces Pacific Ocean landing (video).

According to the Trump team, the orders will:

— Reinvigorate America’s beautiful clean coal industry

— Lift Biden-era restrictions on coal plants

— Strengthen the reliability and security of the electric grid

— Protect American energy from overreach by radical leftists in the states

It will also expedite leases for coal mining on federal lands.

What a stark contrast with the clueless Biden.

Well, Biden was merely a puppet carrying out the wishes of his boss: “If somebody wants to build a coal-powered plant, they can–it’s just that it will bankrupt them.”

KAROL MARKOWICZ: Democrats lit the ‘assassination culture’ fuse — now their silence equals violence.

“We are at war,” Rep. LaMonica McIver (D-NJ) shouted in February, as she denounced what she called Trump’s “hostile takeover” of the government he was elected to lead.

“We have to fight in the streets,” said Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.).

Now, the fuse is lit — and the elected firebrands have nothing to say.

Voters chose Trump, very recently and very specifically, to shake Washington up.

It’s OK to protest, to loudly oppose the changes Trump was elected to make. That’s part of America’s political legacy.

But “assassination culture,” as the lead author of the NCRI report calls the new spike in violent rhetoric, is not.

Democrats don’t get a pass on it this time. They set this ball rolling; they own it. Their silence now is encouragement.

They need to be the ones to stop it. Time to take responsibility and lower the temperature.

Read the whole thing.

“WE’RE HELPING CLEAN UP THE PLANET:” “Voilà. Over 150 barrels of human shit.”

HOW PRINCETONIANS SAVED THE GREAT GATSBY:

At the start of the 1940s, F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917 was, as the kids say, in his flop era. In the first year of that decade, the total sales for all of Fitzgerald’s books, from This Side of Paradise to The Great Gatsby, were a whopping 72 copies. The amount of scholarly ink spilled on him could fit into a thimble. When Fitzgerald died in December 1940 — of a heart attack, at the age of 44 — the world’s verdict on the author was that he was a tragic figure: a sort of literary sparkler who burned too bright, too young, then fizzled out when his decade did, enjoying great celebrity during the Jazz Age and losing it all in the 1930s when the public had too many worries to care about flappers and champagne.

His early death was all the crueler, critics said, because it came late enough for him to see the collapse of his youthful promise. On his 40th birthday, the New York Post published a profile that depicted him as a washed-up alcoholic who knew his best days were behind him, interesting only as a symbol of the failures of his generation:

Then the reporter asked him how he felt now about the jazz-mad, gin-mad generation whose feverish doings he chronicled in This Side of Paradise. How had they done? How did they stand up in the world?

“Why should I bother myself about them?” he asked. “Haven’t I enough worries of my own? You know as well as I do what has happened to them. Some became brokers and threw themselves out of windows. Others became bankers and shot themselves. Still others became newspaper reporters. And a few became successful authors.”

His face twitched.“Successful authors!” he cried. “Oh, my God, successful authors!”

He stumbled over to the highboy and poured himself another drink.

If it were up to the world, perhaps that would still be his legacy: an obscure figure whose works scholars cite on rare occasions, but not someone whom readers or critics care about. Most books, as an eminent librarian once said, have rarely been read. But the pantheon of artistic greatness isn’t up to the world only. From time to time, Princeton intervenes to correct the world’s mistakes.

This year is the 100th anniversary of the publication of The Great Gatsby. Though today Fitzgerald’s novel is covered in honors — a perennial on lists of the greatest American novels, a staple in the classroom, the subject of movies and Broadway musicals — it owes its place in the canon to a valiant company of students, professors, and alumni from his alma mater. Though he was, for a time, forgotten, Princetonians recognized Fitzgerald as their poet laureate and kept his fire burning long enough for the world to recognize the lasting value of his work.

As artists even better than him have done — Mozart is an example — Fitzgerald died in penury. He was living in a girlfriend’s apartment in Los Angeles, drinking too much and scratching up a bare living by writing screenplays. At the time of his fatal heart attack, he was reading an issue of the Princeton Alumni Weekly.

Just 30 people came to his funeral. The newspapers covered his death, but the story they told was a tragedy of youthful talent squandered: “Roughly, his own career began and ended with the Nineteen Twenties,” said The New York Times. “The promise of his brilliant career was never fulfilled.” “Poor Scott,” Ernest Hemingway said of him, and the label stuck. Poor Scott, who died in the worst way an artist can die: too early, but late enough to see himself forgotten.

* * * * * * * *

In the meanwhile, World War II was raging, and the U.S. government launched a curious wartime initiative that played an unexpected role in Fitzgerald’s literary comeback.

The military collaborated with the publishing industry to send free books to servicemen abroad, putting together a Council on Books in Wartime in 1942, with a board of directors assembled from top publishing executives, to choose the books that would be selected for this purpose. (The records of the Council on Books in Wartime are at the Princeton University Library.) Once chosen, the books were reprinted in a new format, the Armed Services Editions. Small enough to fit in a pocket, these books were printed on newsprint paper, which meant they were incredibly cheap to make.

The Council chose two of Fitzgerald’s books for this series: The Diamond as Big as the Ritz and Other Stories and The Great Gatsby. Why these books? Scholars have suggested different theories. Publishers were the ones who offered titles for the council to choose from, and perhaps Scribner’s offered up Fitzgerald’s works so it could do its wartime duty without giving up truly valuable titles. Perhaps the council was running out of bestselling fiction, or perhaps it thought the setting of Gatsby, a period of postwar prosperity to the point of excess, would hearten young men who were looking ahead to a new postwar period after the fighting.

Whatever the case, the Armed Services Edition of The Great Gatsby — a handsome little green affair, 222 pages long and weighing just 2.3 ounces — put the novel into the hands of some 155,000 readers. A capsule biography of Fitzgerald that follows the novel’s text calls Gatsby “his greatest novel” while rehearsing the story of his ruined promise: “F. Scott Fitzgerald gave a name to an age in American life, lived through the age, saw it burn itself to a grim cinder — and wrote finis to it. Few authors have such an achievement to their credit.”

In 2019’s “The Great Forgetting,” Kyle Smith wrote:

As the Who suit up for what I suppose will be their final tour (“Who’s Left”?), Chuck Klosterman points out in his book But What if We’re Wrong? that whole forms die out. He compares rock to 19th-century marching music: nothing left of the latter except John Philip Sousa. That’s it. And Sousa himself is barely remembered. In 100 years rock might be gone too, Klosterman guesses. Maybe we’ll remember one rock act. Who will it be? Maybe none of the obvious answers. It certainly wasn’t obvious at the time of Fitzgerald’s death that The Great Gatsby would be the best-remembered novel he or anyone else wrote in the first half of the 20th century. As for the novels of the second half of the 20th century, the clock is ticking on them. The Catcher in the Rye is moribund. Generation X was the last to revere that book. Teaching it to young people today would get you ridiculed. To Kill a Mockingbird? It had a good run but it’s now being labeled a “white savior” story by the grandchildren of those who revered it. Soon schools and teachers will be shunning it.

Exit question: Why Can’t Hollywood Get The Great Gatsby Right?

(Via Virginia Postrel.)

Is it really “efficiency” if you have to run your dishwasher twice to get your dishes clean?

STANDING ON PRINCIPLE:

This guy didn’t resign when IRS employees leaked the sensitive tax information of 405,000 citizens to ProPublica, but draws the line at a legitimate law enforcement request for information on non-citizens. https://t.co/AFTyzkIqlo

— Parker Thayer (@ParkerThayer) April 8, 2025

“ARE WE THE BADDIES?” It Would Be Super Cool if the Democrats Weren’t Always Rooting for the Bad Guys.

FASTER, PLEASE: Gene discovery reveals potential for growing new heart arteries.