MIKE SOLANA: Bad Ghibli.

Regardless of the quality, it was hard to argue the avalanche of AI-generated images we saw last week, grasping for attention in a kind of life-like mass beyond anyone’s control, wasn’t slop-like, and I alluded to as much that afternoon. Later, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman responded on X, “One man’s slop is another man’s treasure.” Different strokes for different folks, case closed. But the conversation on slop, in keeping with its basic nature, was a bit of a distraction.

It was Sam’s following tweet that exposed a real — and in my opinion really fascinating — problem:

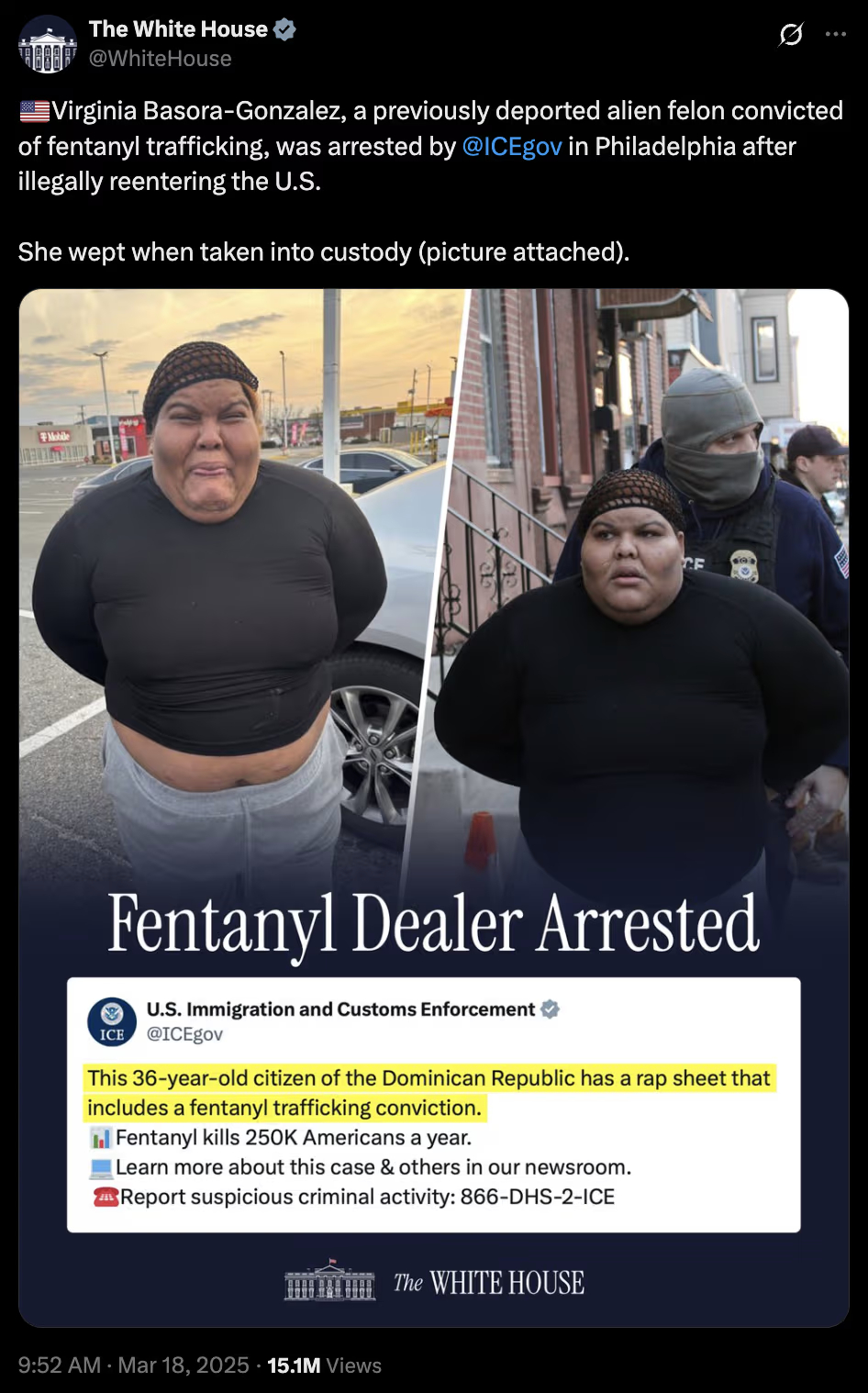

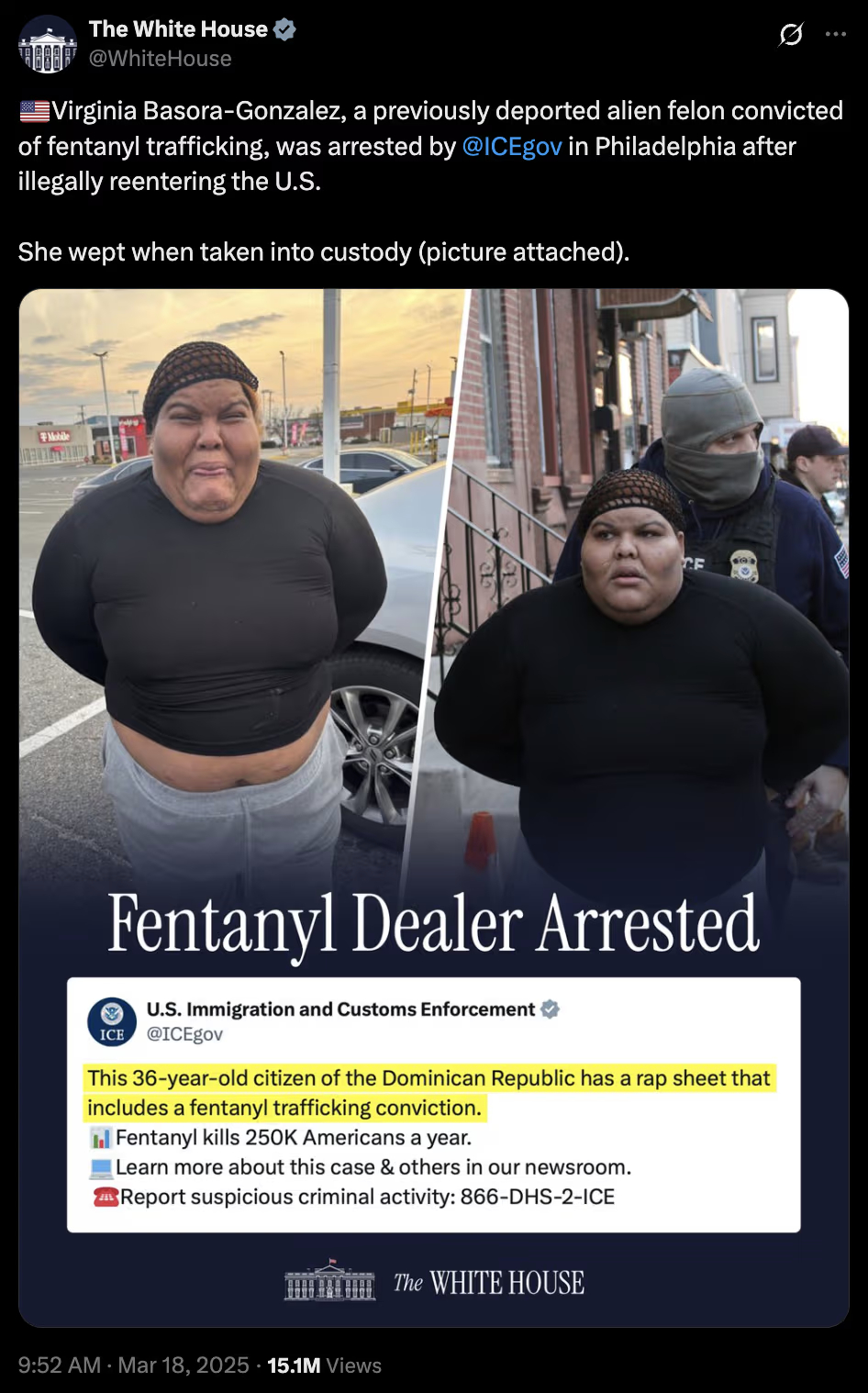

Obviously, he was alluding to the White House social media team’s Ghibli, now the most famous example of OpenAI’s new image generation by far. And the first really great, and really impactful, example of bad AI-generated art:

A bad Ghibli, we’ll call it. A piece of AI-generated art that is incredibly successful — at conveying something you didn’t intend to convey.

* * * * * * * *

While it’s hard to know exactly what the White House social media team was trying to achieve with its Ghibli (though my sense is probably nothing, and they were simply working from instinct as most of us are online), I think it’s safe to say they didn’t want to evoke a sense of pity in the average American for a deported fentanyl dealer. But that is what they achieved.

The moment their Ghibli went viral, and the first wave of backlash began, many hardline supporters of the White House were quick — naturally, correctly — to point out this was an AI-generated picture of a felon, almost certainly responsible for the death of Americans, who had already been deported once before. She was also, in real photos that emerged, (I am not being petty here, this is important) physically repulsive. Just look at her, the bad Ghibli defenders cried. And I understand the impulse. I mean, take a look yourself:

Who wants this person in their country? Nobody. Who cares if she cries on her way home? Not me. But, incredibly, in order to defend the cartoon, White House allies had to point to the real photo of an actual criminal, which the White House had already released at the time of the Ghibli. In this, we are not using imagery to massage or explain away reality, as we often see with propaganda. We are using reality to explain away an entirely generated controversy that happened, it seems to me, by mistake. Because someone who is not an artist generated real art he didn’t understand.

How did we get here?

Read the whole thing.

In his early days as creator/producer of Saturday Night Live, Lorne Michaels once rejected a potential sketch by telling its writer that it suffered from “premise overload.” In 2022, Biden’s infamous nighttime Independence Hall speech rant was the result of his handlers trying to put him in a real-life “Dark Brandon” scenario, which thrilled his hyper-online far left base and left the vast majority of Americans confused and angered by the Leni Riefenstahl-like images they were seeing. Similarly, the Trump comm team’s confusing AI slop last week was premise overload as well. I didn’t make the connection with Basora-Gonzalez, and I initially pondered if the man in the cartoon was some sort of Tim Walz callback, given his rounded face and middle-aged appearance, and Walz’s comical obsession last year with camouflage-colored haberdashery.

Solana concludes, “Be careful what you prompt for.” I would argue, prompt away; ChatGPT’s ability to effortlessly spitout Ghibli cartoons is lots of fun, but a political comms shop needs to make sure that the vast majority of the people seeing the image will connect with it before deciding to hit the publish button on social media.