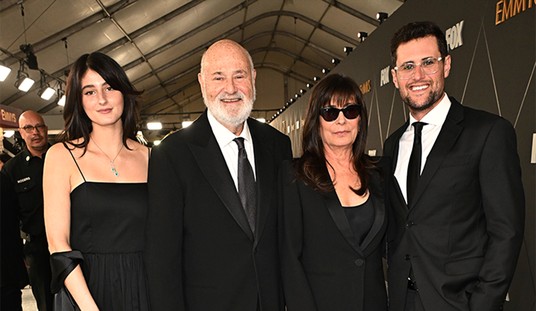

This New Year’s Eve a South Carolina man returned to a party at his parent’s house and overheard a struggle inside the master bedroom. He kicked down the door to discover his girlfriend being raped by his uncle, William Mattson (52). The image above depicts the pounding the nephew unleashed on his uncle as a result. And when Mattson tried to tell police that the sex was consensual, the nephew attacked him again in front of police officers.

Mattson’s nephew wasn’t technically in danger – his girlfriend was – so would Mattson win a lawsuit if he took his nephew to court for attacking him without justification? There are many myths and misconceptions surrounding the notion of “criminal rights.” Perhaps the most famous anecdote involves an intruder burglarizing your house, injuring himself in the process, and then suing you in court. Like most rumors, there is truth and fiction in many of these criminal-rights anecdotes.

Retaliation against a criminal almost always boils down to “self-defense.” According to the law, you are entitled to defend yourself and your property as long as you do not use excessive and/or unreasonable force. In Michigan, in November of 2007, Scott Zielinski sued the store he tried to rob after the owner and some employees chased him out onto the street, caught him, and proceeded to beat him half to death. He was seeking $125,000, but the case was dismissed when the judge required that Zielinski post a $10,000 bond first. He was unable to afford this, otherwise the case might have had credence. However, in England in 2008, a burglar, Daniel McCormick, was actually awarded the equivalent of $250,000 after an angry homeowner scared him off his property and then proceeded to run him down in his BMW and break both of his legs. The rule here is to be weary when self-defense turns into vengeance. Mattson’s nephew’s actions were considered self-defense because he was acting on behalf of the victim, essentially defending her safety.

But the ambiguity doesn’t end at self-defense – there’s still the notion of negligence. An incident in 1982 in California, Bodine vs Enterprise, is likely where this annoying concept of “criminal compensation” originated. Nineteen-year-old Ricky Bodine was on the roof of the Enterprise High School gymnasium, but according to legal documentation it’s unclear what his motive was. Some say he was stealing a flood light, while his friends say he was “redirecting” a light because they were playing basketball — but either way he was trespassing. Bodine took a misstep while on the roof and plunged through a skylight, thus falling to the gymnasium floor and turning himself into a paraplegic. His family tried to sue the school to compensate for the negligent conditions on the roof: the fragile skylight was actually painted black, making it virtually indistinguishable from the rest of the rooftop.

A similar incident occurred in 2011 when New York Senator James Alesi, while house-hunting, entered an unoccupied home that was under construction to get a self-guided tour of the inside. Alesi had to climb a ladder to exit the basement, fell off the ladder, and broke his leg. After filing a personal injury claim against the construction company, word of this case got out and Alesi became a laughingstock. Shortly thereafter a moment of clarity descended upon him and he decided to drop the lawsuit.

There is an apparent contradiction in our laws regarding property protection. In the eyes of the law, defense of yourself and defense of your property are considered the same thing (e.g. you are justified to use force to protect both). But the law also states that life has a greater value than property (e.g. execution is excessive in response to petty theft). Where this contradiction finds its resolution is in a troublesome aspect that few would consider: booby traps.

Booby traps can be dangerous legal territory to tread upon because the homeowner’s imminent safety and the concept of “excessive force” are both in question. A relatively famous case took place back in 1971 in Iowa when Edward Briney set up a trap in the bedroom of an unoccupied farmhouse on his property, which had been looted several times despite the “no trespassing” signs. Five days after the trap was set, Marvin Katko trespassed to “collect” some old bottles and jars that Briney considered antiques, and sprung the trap: a 20-gauge shotgun aimed leg high. The trap worked and Katko had to be hospitalized. He was eventually awarded $30,000 after the court ruled that a shotgun booby trap is excessive force on an unoccupied property.

In 1997, a more recent version of this occurred in Illinois when Larry Harris (37) broke into a tavern where a booby trap awaited him. While climbing through the window, Harris placed his hand on an electrified bar and was electrocuted to death. Harris’ family sued the tavern’s owner over a wrongful-death claim.

Before you dismantle that spring-loaded AK-47 above your porch, let’s establish some perspective on some of these lawsuits. The average wrongful death settlement in America is around $1 million, and Harris’ family received $75,000 (8% of the average). The average personal injury settlement for a paraplegic is around $13 million, and Bodine received $260,000 (5% of the average, scaled against inflation). Criminals appear to receive less than a tenth of the financial sympathy a jury would afford a law-abiding citizen. Another thing to keep in mind is that the financial victories listed in this article represent some of the best examples we have of excessive force and negligence when addressing criminal rights. Most of the lawsuits you hear about involving robbers who sue homeowners because they got shot are laughed out of court.

If our laws do protect criminals, to some degree, are stricter laws the answer if we want to reduce crime in America?

Some countries with very low crimes rates, like Japan and Singapore, boast firm law enforcement procedures. While some countries with higher crime rates, like Cuba and North Korea, also have strict law enforcement practices. And some of the most lenient nations on crime, like Sweden and Canada, actually have some of the lowest crime rates. The statistics may not yield a definitive answer, but in the meantime I hope the reduced compensation (5 -8% of the average settlement) has the attorneys thinking twice before they choose to represent a criminal in civil court.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member