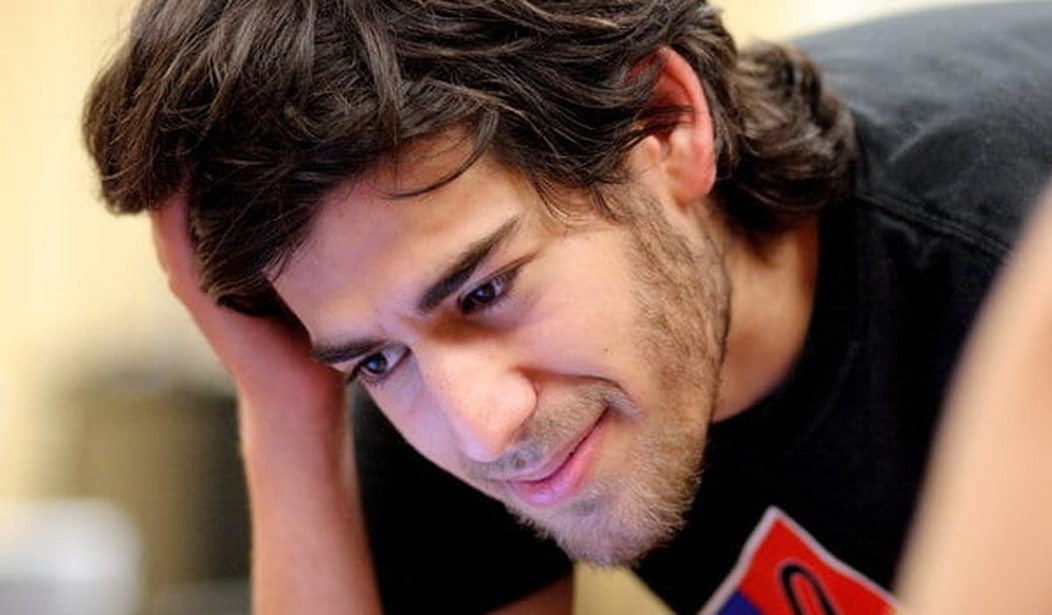

Details of the Justice Department’s treatment of an Internet activist who committed suicide has stoked fresh outrage on Capitol Hill, with the chairman of the House Oversight Government and Reform Committee demanding answers from Attorney General Eric Holder about the findings of a probe into the death of Aaron Swartz.

In January 2011, Reddit co-founder and RSS creator Swartz, who lobbied for freedom of information on the web, was arrested for downloading millions of academic articles from the digital library Journal Storage (JSTOR) in protest of the weighty fees charged for accessing articles, and those dollars going to publishers instead of writers.

“We need to take information, wherever it is stored, make our copies and share them with the world,” Swartz wrote in 2008. “We need to take stuff that’s out of copyright and add it to the archive. We need to buy secret databases and put them on the Web. We need to download scientific journals and upload them to file sharing networks.”

JSTOR declined to pursue any civil action against Swartz, and even eventually made millions of its articles accessible to the public free of charge. “Aaron returned the data he had in his possession and JSTOR settled any civil claims we might have had against him in June 2011,” JSTOR said in a statement “mourning this tragic loss” after Swartz’s death.

The Justice Department, though, slapped Swartz with charges including wire fraud and computer fraud, altogether carrying the possibility of 35 years behind bars and up to a $1 million fine. Prosecutors eventually offered Swartz a deal to avoid trial in which he’d have to plead guilty to all 13 charges and spend six months behind bars.

Two days later, on Jan. 11, 2013, Swartz hung himself in his Brooklyn apartment. He was 26 years old.

The news initially sparked the interest of Oversight Chairman Darrell Issa (R-Calif.), a foe of the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) along with Swartz, and Sen. John Cornyn (R-Texas), who queried Holder about the prosecution of the young web whiz both in a January letter and at a March Senate Judiciary Committee hearing.

“Does it strike you as odd that the government would indict someone for crimes that would carry penalties of up to 35 years in prison and million dollar fines, and then offer him a three or four month prison sentence?” Cornyn asked.

“I think that’s a good use of prosecutorial discretion…” Holder responded.

“So you don’t consider this a case of prosecutorial overreach or misconduct?” pressed Cornyn.

“No,” Holder replied.

MIT, whose archive was hacked while Swartz was a fellow at Harvard (which gave him access to JSTOR), launched an internal investigation into the case.

The report, issued July 30, notes disagreement between the school and the U.S. Attorney’s Office on how Swartz would be treated.

“MIT’s counsel noted that no one at the Institute was looking forward to the time, disruption and stress involved in testifying at hearings and trial. The prosecutor’s response was that it disturbed him whenever a defendant ‘systematically re-victimized’ the victim, and that was what Swartz was doing by dragging MIT through hearings and a trial. He analogized attacking MIT’s conduct in the case to attacking a rape victim based on sleeping with other men,” the report states.

“MIT’s counsel stated that, while the government might believe that jail time was appropriate in this case, the government should not be under the impression that MIT wanted a jail sentence for Aaron Swartz. The prosecutor responded that the government believed that some custody was appropriate. He said the government had to consider not only the views of the immediate victims, but also general deterrence of others.”

The report also suggests that the DOJ came down on Swartz harder because he went public with the case and his allies launched a petition drive on his behalf.

“The prosecutor said that the straw that broke the camel’s back was that when he indicted the case, and allowed Swartz to come to the courthouse as opposed to being arrested, Swartz used the time to post a ‘wild Internet campaign’ in an effort to drum up support. This was a ‘foolish’ move that moved the case ‘from a human one-on-one level to an institutional level.’ The lead prosecutor said that on the institutional level cases are harder to manage both internally and externally.”

The lengthy report also describes a meeting with Aaron’s father, Robert Swartz, in which he “accused MIT of violating wiretap laws and its internal policies in its collection of electronic communications of his son and providing them to the prosecution, and of violating his son’s privacy rights in doing so.”

In a letter to Holder on Wednesday, Issa noted that “despite the fact that the Justice Department was aware of the positions of the victims regarding Swartz’s prosecution, it proceeded to investigate and prosecute Swartz vigorously.”

The comparison to a rape trial noted in the MIT report “raises questions about the mindset of the prosecutors handling the case,” the chairman added.

“The report also indicates that the Department elevated its charges against Swartz in response to an Internet campaign conducted by Demand Progress in support of Swartz at the time of his arrest,” Issa continued. “…The suggestion that prosecutors did in fact seek to make an example out of Aaron Swartz because Demand Progress exercised its First Amendment rights in publicly supporting him raises new questions about the Department’s handling of the case.”

Issa asked Holder to arrange a meeting with committee staff on the Swartz case by Aug. 13. By the afternoon of Aug. 12, the DOJ had not reached out to arrange that briefing.

In response to a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit pursued by Wired investigations editor Kevin Poulsen, the Secret Service today released 104 pages of heavily redacted documents kept on Swartz.

The documents confirmed that the government’s interest in Swartz was piqued after a 2008 manifesto he wrote describing his beliefs that open access is a human right.

There are still 14,500 more pages of government documents on Swartz to be released by court order; Poulsen said he’s been given a processing time estimate of six months before all are released.

In June, Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) and Reps. Zoe Lofgren (D-Calif.) and Jim Sensenbrenner (R-Wis.) introduced Aaron’s Law Act of 2013. It would reform the quarter-century-old Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) to establish that breaches of terms of service, employment agreements, or contracts are not automatic violations of the CFAA.

Lofgren’s office said “by establishing a clear line that is needed in the law, it distinguishes the difference between common online activities and harmful attacks.”

“Aaron worked closely with my office on a number of civil liberties issues,” Wyden said at a memorial for Swarz in February. “…Aaron was a hacker. He hacked to promote innovation through openness. Where Aaron saw injustice, he hacked for its remedy. Aaron Swartz hacked Washington. A poorly written law called him a criminal. Common sense and conscience knows better.”

Join the conversation as a VIP Member