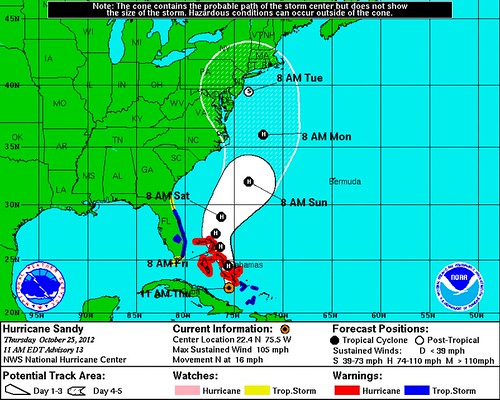

Hurricane Sandy’s development was impeded a bit by Cuba — it likely would be a Category 3+ right now, if a mountainous land mass had not intervened — but it remains a powerful Category 2 hurricane, with 105 mph winds and a barometric pressure of 963 mb, as it moves into the Bahamas. And the National Hurricane Center’s 11:00 AM forecast has shifted west, following the consensus of the computer models, to squarely target the U.S. East Coast:

You should not focus on the exact forecast track, particularly in the latter parts of the forecast, as the details are still very uncertain at this point. Everyone in the “cone of uncertainty,” from North Carolina to New England, should begin preparing for the possibility of hurricane-like conditions late this weekend or early next week. Also — another reason to focus on the cone, not the exact track — Sandy will have a very large wind field, with bad weather quite far away from the center. So a large area is going to be impacted by this storm.

[NOTE: For my latest updates on Sandy, follow me on Twitter.]

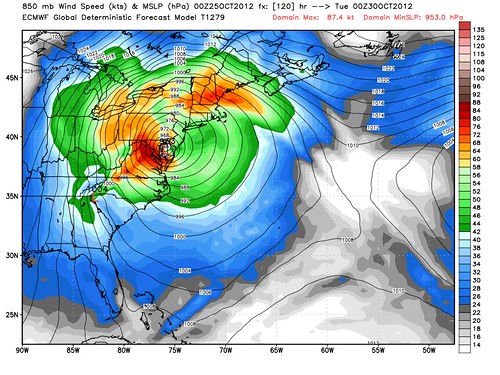

Widespread, long-lasting power outages are almost a given with a storm like this. Wind damage will be significant, particularly with leaves still on the trees (as opposed to winter Nor’easters), and particularly with heavy wind over such a wide area, which means affected areas will take a prolonged battering. Severe coastal flooding is also a serious threat, primarily north and east of wherever the storm’s center makes landfall. (Monday is astronomical high tide, making things worse.) Severe inland flooding from heavy rainfall is another big potential problem. Places where those two phenomena can happen simultaneously — for instance, the mouth of the Delaware River, where it flows into Delaware Bay — are especially at risk, if the center comes in just to their south. Which, as it happens, is exactly what the 00z run of the European model predicts for Delaware Bay:

Yikes. I don’t want people to #PANIC about a specific model or a particular model run; any individual scenario is unlikely at this point, because there is still a lot of time and a lot of uncertainty. However, that particular scenario — what Joe Bastardi calls the “Philadelphia Story” scenario — is one of many that’s “in play” at the moment, which is distressing. Likewise, a New York harbor nightmare is another scenario that’s in play.

Aside from all the “usual” impacts of a hurricane transitioning into an uncommonly severe hybrid coastal storm and impacting the Megalopolis, this storm is going to hit one week before a presidential election, which raises a whole host of additional concerns. I discussed some of these yesterday, including the possibility that the occurrence of a national emergency could alter the dynamic of the campaign in its final weeks. But right now, I want to focus on the procedural issues, the impacts on the actual conduct of the election itself. For instance:

• Additional chaos and “irregularities” on Election Day due to lost “prep” time. I spoke this morning with my father, a retired elections bureaucrat in Connecticut, and he made the excellent point that the week before the election is very busy for folks like him in his old job, and for registrars of voters, town clerks and the like. They’re testing voting machines, printing ballots or other critical papers, and doing all sorts of other mundane tasks that are critical to assuring a smooth Election Day. If the impact of the storm wipes out all or part of that critical “prep week,” then even if things are relatively “back to normal” by Election Day (by no means a given; see below), there would likely be an invisible storm impact in the form of additional chaos, “irregularities” and all manner of disruptions at the polls — failed voting machines, missing ballots, etc. — simply because the officials had to cut short their preparation, so more mistakes will inevitably happen. This, in turn, will increase the already-high likelihood of cries of fraud (from Republicans) and suppression/disenfranchisement (from Democrats) in the event of any remotely close outcome. Basically, Sandy is likely to make an already highly charged atmosphere surrounding the conduct of the election even moreso.

• Lower turnout impacting various elections, and possibly giving Mitt Romney the national popular vote. If power remains out, some roads remain impassable, and people’s lives are generally disrupted in a myriad of ways a week after the storm in heavily affected regions (all of which seems entirely plausible), it is likely that lower turnout would result. This is especially true in states where the presidential race is not hotly contested — basically, the entire region except for New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Ohio — so voters may be less-motivated to vote, and the campaigns would certainly be less-motivated to pull out all the stops to help them do so amid difficult circumstances. If turnout is particularly affected in Democratic strongholds like New York, much of New England, Maryland, etc., it could depress President Obama’s national popular vote numbers, and help make an already much-discussed scenario even more likely: Obama wins the electoral vote and thus the presidency, but Romney wins the national popular vote (essentially, a reverse of the Gore/Bush result in 2000).

Of course, lower turnout in Virginia, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, and/or — above all — Ohio, would be far more significant, as it could impact the Electoral College outcome. The nature of such an impact is a little hard to gauge, though. Obviously, it depends on which regions within those states are hardest hit. For instance, if Philadelphia is ravaged by Sandy, it could be an enormous problem for Obama, turning a state that appears to favor him into a real tossup, and perhaps a national tipping-point state. Conversely, if western Pennsylvania is hit especially hard — whether by copious rain and strong winds, or possibly by heavy snow (!) — it could hurt Romney, and put the Keystone State far out of his reach. Similar analyses would hold in other states where the voting patterns are very regional.

More broadly, due to the “enthusiasm gap,” among other factors, low turnout probably favors the Republicans, at least in states without early voting. In states with widespread early voting (like Ohio), low Election Day turnout probably favors whichever party is doing better in early voting. I have no idea what the impact would be on key Senate races in places like Connecticut, Massachusetts and Virginia (and to a lesser extent the marginally close races in Pennsylvania, Ohio and Maine); it presumably would depend in part on the local “enthusiasm gap” there vis a vis the Senate races, but I don’t know what those numbers look like.

• Widespread power outages causing disruptions in voting. This one seems highly likely to occur, in some form or another, in various places. Think back to Hurricane Isaac, or the summer derecho, or last year’s Halloween snowstorm. Widespread power failures don’t just get fixed overnight. A week after the storm, significant portions of the hardest-hit areas will likely still be without power. What will this mean?

Well, the first question to ask is, what kind of voting machines do the potentially affected areas use? VerifiedVoting.org has a helpful map showing the types of systems in use, state-by-state — and county-by-county, if you click on an individual state (for instance, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Ohio). You can even click on the county and find out the specific manufacturer of the machine they use there.

As it happens, all of New England and New York apparently uses “optical scan” paper ballots, which means the process of voting can theoretically take place without electrical power (although it may be difficult to see the ballot without lights!). Typically, as I understand it, voters submit their ballots by feeding them into the optical scan machine, which may or may not have enough battery power to continue working in such an environment (I don’t know that answer, and suspect it varies from manufacturer to manufacturer). But, worst-case scenario, presumably the ballots can be placed in a box, then submitted to the optical scan machine later, once power is back on. This could severely delay the counting of ballots (more on that later), but would not prevent people from voting.

More potentially problematic are the “DRE” (direct-electronic recording) machines, usually called “touch-screens.” Those are used throughout all of New Jersey, Maryland and Delaware, and most of Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia and Ohio. For instance, Pennsylvania’s Philadelphia and Delaware counties — which would be very hard-hit in the Bastardi/EURO scenario — both use Danaher Controls’ Shouptronic 1242 model. Good news there: according to a report (PDF) by the Department of Elections for New Castle County, Delaware, the Shouptronic 1242 is supposed to keep functioning even when the lights are off:

In the event of a power outage the Electronic 1242 is equipped with a battery backup adequate to maintain normal operation for up to 16 hours. The internal power supply maintains the battery charge when power line voltage is normal to assure that the backup battery is fully charged and immediately ready for use if the AC power fails.

Assuming the battery is fully charged before the power goes out, and assuming the machine remains off until Election Day, that would seem to be good enough to keep things going. But I have no idea (and don’t have to check) whether every DRE system is equally robust, or if those 16-hour assurances have been fully tested, etc. And in the event of widespread machine failure, don’t just assume “oh well, people will just use paper ballots instead.” It’s not that simple. Election officials do not routinely print enough paper/provisional ballots for the entire electorate to use them. If the regular voting machines don’t work, there will be mass chaos at the polls — and probably a great deal of disenfranchisement — unless these places have a very good contingency plan, and put it into place well in advance.

Moreover, my point about polling places lacking electricity and lighting is not a trivial concern, even if the machines themselves are workable. The many thousands of polling places in school gymnasiums, local libraries and whatnot aren’t typically hardened against power outages, and likely lack a contingency plan for bringing in generators and such on short notice. It is easy to imagine last-minute changes in polling place locations, many voters trying to vote in the “wrong” precinct because theirs lacks power, etc. At a minimum, I would anticipate a whole lot of chaos, confusion, and a higher-than-usual number of provisional ballots being cast.

• Widespread power outages causing major delays in vote-counting. Casting ballots is one thing; counting them is another; and communicating those vote counts to a central location is yet another. We are used to rapid vote counts filling our screens on Election Night, telling us who the winner is (albeit based on unofficial returns) within a matter of hours, except when the result is razor-close like in 2000. However, such speedy counting depends on thousands of local polling places having the ability to tally and transmit their vote totals shortly after the polls close. Without diving too far into the weeds again, it’s easy to imagine widespread power outages causing all sorts of disruptions to this process. Consequently, we could easily see a number of states with uncommonly slow vote counts. If the slow-counting state is, say, Vermont or Maryland, nobody will much care nationally; if it’s, say, New Hampshire or Virginia, it could make for a frustrating night.

More after the jump.

• Evacuations causing massive disruption and controversy. Imagine for a moment that Hurricane Katrina had hit a week before a presidential election, and that Louisiana and Mississippi had been swing states. I actually can’t really imagine it — the disruption would have been unbelievable, the controversy uncontainable, the outcome unpredictable. How on earth do you handle a situation where thousands upon thousands of voters are, through no fault of their own, displaced at the last minute — missing whatever absentee or mail-in ballot deadlines might have existed — and consequently unable to vote? You can’t locally delay the election without creating an unfair and legally questionable situation (more on that in a moment), but it’s also obviously unacceptable to have a whole swaths of voters disenfranchised. I don’t care if those voters are Republicans or Democrats: it’s undemocratic and un-American to have a storm wipe out, or substantially dilute, a whole region’s voice in a national election.

Sandy is by no means equivalent to Katrina, but it could certainly lead to evacuation orders this weekend for coastal and flood-prone areas in its target zone, and it’s conceivable that those evacuation orders might not be lifted for some time after the storm if power outages, downed trees and power lines, inland flooding, etc. create a witch’s brew of unsafe conditions in the affected areas. If those areas happen to be located in a swing state, or a state with a major Senate race, it is easy to imagine decisions about when to lift evacuation orders becoming intensely politicized.

A nightmare scenario for Democrats would be an evacuation of portions of Philadelphia, which would not only endanger Bob Casey, but would take a state that Obama seems likely to win unless he’s losing swing states across the board (and thus the PA outcome doesn’t really matter), and turn it into a potentially decisive tipping-point state that could hand Romney the presidency even if he loses Ohio and most of the other swing states. Now, to be frank, I’m not sure how realistic a major Philly evacuation is — Philadelphia obviously is not New Orleans; most of the city seems not to be in a flood zone — but then, I don’t know my Pennsylvania political geography that well, so perhaps somebody can help me out there. [UPDATE: Sean Trende has created some maps of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania showing the partisan composition of the areas shown by flood risk maps as having, respectively, moderate and mild flood risk.] In any case, just for the sake of argument, what would happen if voters, from whatever region in PA, are displaced through Election Day? Pennsylvania’s law on absentee ballots would make it pretty difficult to resolve such issues on a large scale at the last minute:

In Pennsylvania, the County Board of Elections must receive your application for absentee ballot no later than 5 p.m. on the Tuesday before the election. In emergency situations (such as an unexpected illness or disability) you can submit an Emergency Application for Absentee Ballot, which must be submitted no later than 5 p.m. on the Friday before Election Day. Completed non-emergency absentee ballots must be received by 5 p.m. on the Friday before Election Day. In presidential election years, absentee ballots received by the close of the polls on election day will be counted for the offices of president and vice president. …

Emergency Absentee Ballot Applications are available at the county Board of Elections Office. If you have an emergency and did not apply for an absentee ballot by 5 p.m. on the Tuesday prior to Election Day, you may download and apply for an Emergency Absentee Ballot. This application must be notarized before it is submitted. …

If you become physically disabled or ill between 5 p.m. on the Friday before Election Day and 8 p.m. on Election Day or if you find out after 5 p.m. on the Friday before Election Day that you will be absent from your municipality of residence on Election Day because of your business, duties or occupation, you can receive an Emergency Absentee Ballot if you complete and file with the Court of Common Pleas in the county where you are registered to vote an emergency application or a letter or other signed document, which includes the same information as that provided on the emergency application. …

If you are not able to appear in court to receive the ballot, you can designate, in writing, a representative to deliver the absentee ballot to you and return your completed absentee ballot to the County Board of Elections. If you are not able to appear in court or obtain assistance from an authorized representative, the judge will direct a deputy sheriff of the county to deliver the absentee ballot to you if you are at a physical location within the county.

Emergency Absentee Ballot Applications from voters who experience an emergency after 5 p.m. on the Friday before Election Day must be submitted to the Court of Common Pleas no later than 8 p.m. on Election Day.

Needless to say, that system is not set up to deal with thousands of residents applying for Emergency Absentee Ballots between next Tuesday and next Friday, let alone thousands who might “find out after 5 p.m. on the Friday before Election Day that [they] will be absent from [their] municipality of residence on Election Day” (because as of next Friday, they may still assume that the evacuation orders will be lifted by Election Day, only to subsequently learn that’s not going to happen). If the storm creates a situation where thousands of voters need, at the last moment, to receive an absentee ballot and vote absentee, it will do two things. First, many voters won’t bother; it won’t be worth the hassle, particularly when they’re dealing with a massive disruption in their lives due to the storm. Secondly, those who do bother will overwhelm the normal process, and a court battle would be almost certain.

I haven’t checked the relevant laws in other affected states, but I suspect that similar or related issues abound. Bottom line: if large numbers of voters are still evacuated on Election Day due to the storm, expect chaos. If those voters are from a swing state, expect highly-charged chaos.

• So… can President Obama delay the election? No. Not unilaterally, anyway. Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution states: “The Congress may determine the Time of chusing the Electors, and the Day on which they shall give their Votes; which Day shall be the same throughout the United States.” What we call “Election Day” is actually the day when we “chuse the Electors” who subsequently vote in the Electoral College. And Congress has, as the Constitution permits, set a uniform Election Day. The “Time of chusing the Electors” is set by 3 USC § 1: “The electors of President and Vice President shall be appointed, in each State, on the Tuesday next after the first Monday in November, in every fourth year succeeding every election of a President and Vice President.” This year, that’s November 6.

(As for the “Day on which they [the electors] shall give their Votes,” that is set by 3 USC § 7: “The electors of President and Vice President of each State shall meet and give their votes on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December next following their appointment at such place in each State as the legislature of such State shall direct.” This year, that’s December 17.)

Modifying 3 USC § 1, to reset the national Election Day, would require an act of Congress. Such an act would not, per my reading anyway, violate the Constitution, which only requires that “Day on which they [the electors] shall give their Votes…shall be the same throughout the United States”; there is no constitutional requirement that the “Time of chusing the Electors” (Election Day) be the same in every state. However, 3 USC § 1 does set a national election day, so an executive order would not suffice to reset it. An Act of Congress, which of necessity would have to be bipartisan (since the GOP controls the House, and can filibuster in the Senate), would be needed.

Unless…

There appears to be something of an escape hatch in 3 USC § 2, which states: “Whenever any State has held an election for the purpose of choosing electors, and has failed to make a choice on the day prescribed by law, the electors may be appointed on a subsequent day in such a manner as the legislature of such State may direct.” That language is a little confusing in a circumstance like this, since presumably an advance decision to delay the selection due to Sandy would mean that the state in question has NOT “held an election for the purpose of choosing electors,” in which case the statute, as written, seemingly does not apply. However, it is at least possible that a state legislature might attempt to cite 3 USC § 2 in delaying its election. This would of course be very problematic, since it would give the voters of — say — Pennsylvania or Virginia advance knowledge of how other states voted, and thus whether or not they hold the deciding vote. But I guess it could theoretically happen. It would be very, very risky for Democrats to push such a thing through on a partisan basis, however, because any Electoral College disputes are ultimately resolved by Congress, pursuant to an arcane statutory procedure that you might vaguely recall hearing about back in 2000, though it never actually came to that. It is not crystal-clear how such a dispute would turn out, but it is possible that, if the state in question is electorally decisive, the ultimate result could be the same as in a 269-269 tie, with the GOP-controlled House (voting by state delegation, not individual member, so the GOP has a mortal lock on a majority) electing the president and the (possibly) Democrat-controlled Senate electing the vice president. So, as in the 269-269 scenario, we might end up with a Romney-Biden administration, but not with a second Obama term. Accordingly, the Democrats are highly unlikely to risk such an outcome in advance by trying to move Election Day in a place like Pennsylvania (a state they’re favored in anyway) or Virginia (where they at least have a chance) unless it’s almost certain that NOT moving the election would guarantee a Romney win.

The bottom line is that I would be extremely surprised if Election Day is moved, either nationally or locally. However, everything else I’ve described above could very realistically happen, depending on just what Hurricane Sandy does and where it goes. While the details are extremely unpredictable, Sandy could definitely become a big part of the story of this election. Stay tuned.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member