Robert Kuttner, professor at Brandeis University’s Heller School and senior fellow of the think tank Demos, believes that libertarians suffer from a delusion. He claims that the market is incompetent to price certain problems, and must be tightly controlled by government to prevent excess and abuse.

In a piece written for The American Prospect, where he serves as co-founder and co-editor, Kuttner submits examples which he believes demonstrate market failure. We rebutted his analysis in parts one and two of this series.

Kuttner summarizes his critique of the market by fully unveiling his statist economic worldview:

The free market doesn’t live up to its billing because of several contradictions between what libertarians contend and the way the real world actually works. Fundamentally, the free-market model assumes away inconvenient facts. Libertarians presume no disparities of information between buyer and seller, no serious externalities, no public goods that markets can’t properly price (Joan Fitzgerald’s piece in our special report in the Winter 2015 issue of The American Prospect magazine discusses one—water), and above all no disparities of power. But in today’s substantially deregulated economy, bankers have far more knowledge and power than bank customers (witness the subprime deception); corporations have far more power than employees; insurers have more power than citizens seeking health insurance. Labor markets can’t compensate for disparities of power. The health insurance “markets” created by the Affordable Care Act can’t fully address the deeper problem of misplaced resources and excessive costs in our medical system.

Kuttner’s concern over power disparity rings hollow in a context where he advocates for government activism. No private institution, no matter how large or influential, wields the legal monopoly on force bestowed to government. If his complaint is that big banks and large corporations have more power than consumers and laborers, Kuttner loses all credibility by prescribing an institution of even greater power.

Of course, when Kuttner writes about “power,” he’s really referencing private control over private affairs. He’s criticizing property rights and the freedom of association, not an application of force. To his mind, when a bank denies someone a loan, it has exercised “power” over that person’s life. In reality, the denied applicant has lost nothing. They have not been violated. They have not succumbed to force.

By contrast, government activism always applies force. That’s what government is.

That’s the defining characteristic that separates a public institution from a private one – the ability to legally wield force against individuals. By advocating for government activism, Kuttner actually endorses force. He seeks not to curb power, but to concentrate it.

Kuttner also points to a disparity in knowledge. Mom and Pop investors didn’t have the “knowledge” necessary to see through “the subprime deception,” he claims. Here too, his point proves self-defeating.

First of all, it’s absurd to hold up symmetrical knowledge as an ideal. No two people hold the same knowledge about any given transaction, and no principle exists which suggests they ought to. Even if such a principle could be articulated, as a practical matter, there exists no means by which to affect knowledge equality.

Indeed, disparity of knowledge proves natural in society and integral to the functioning of the market. As touched upon in part two of this series, the key benefit of the market is its division of labor. We each specialize in our chosen occupation and defer to the expertise of others by consenting to trade. You don’t have to be an expert in automotive engineering to purchase and make use of a car. Nor would you necessarily want to be.

Before engaging in a transaction, you weigh several factors which substitute for expert knowledge. You consider reputation. You consider the advice of others whom you trust. Above all, you consider price.

Price is the mechanism by which experts communicate their knowledge to non-experts. Price is the collective expression of individuals acting independently in pursuit of their self-interest. It is therefore a measure of value beyond compare. For a price to “lie,” the individuals involved in setting it through expressions of supply and demand would have to abandon their self-interest. A few may, but the overwhelming majority don’t. In this way, price tells us all we need to know regarding the value of a product or service.

To produce an economy that is more equitable as well as more efficient, government uses a variety of tools. It regulates to counteract market failure.

By advocating for government activism, Kuttner seeks to disrupt the price signals which convey knowledge from experts to non-experts. Indeed, as we covered in part two, it was such disruption which caused the 2008 financial collapse. Kuttner claims investors lacked the knowledge to see through “the subprime deception.” He’s right, but fails to recognize the means by which such knowledge is acquired – accurate price signals in a free market. He also fails to recognize the means by which the deception occurred – inaccurate price signals.

Government cannot create or distribute such knowledge. Government can only maintain the condition in which accurate pricing occurs – the condition of liberty. Taxes and government regulations merely keep people from applying their self-interested judgment to the distribution of their earned resources. To the extent capital is taxed away and economic activity is barred by regulation, knowledge which could have been conveyed through price is lost. As a result, remaining resources are to one degree or another misallocated.

The trick which statists like Kuttner like to pull is blaming the market for misallocations caused by government.

The financial collapse serves as a perfect example. Kuttner blames powerful banks for praying on ignorant investors while dismissing the role that government played. Government blunted the risk which banks should have bore, and thus distorted the prices which investors should have paid, which fostered transactions that never should have occurred.

Next time, we’ll get into Kuttner’s reverence for public goods and the proper role government plays in the market. Check back soon.

******

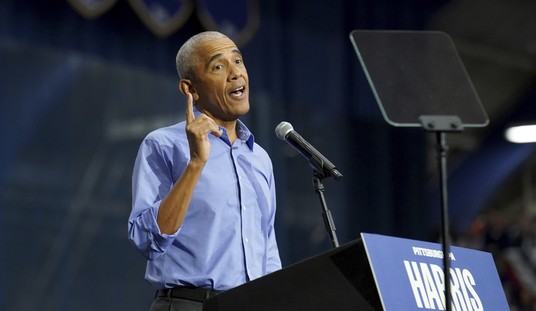

image illustration via shutterstock / advent

Join the conversation as a VIP Member