“Why Our Children Don’t Think There Are Moral Facts” is a topic explored by Justin P. McBrayer, who bio states that he’s an associate professor of philosophy at Colorado’s Fort Lewis College. Curiously though, his article is in the New York Times, a odd location given that it’s a newspaper run by children who don’t believe there are moral facts. But responding to the Common Core syllabus, McBrayer writes:

But second, and worse, students are taught that claims are either facts or opinions. They are given quizzes in which they must sort claims into one camp or the other but not both. But if a fact is something that is true and an opinion is something that is believed, then many claims will obviously be both. For example, I asked my son about this distinction after his open house. He confidently explained that facts were things that were true whereas opinions are things that are believed. We then had this conversation:

Me: “I believe that George Washington was the first president. Is that a fact or an opinion?”

Him: “It’s a fact.”

Me: “But I believe it, and you said that what someone believes is an opinion.”

Him: “Yeah, but it’s true.”

Me: “So it’s both a fact and an opinion?”

The blank stare on his face said it all.

How does the dichotomy between fact and opinion relate to morality? I learned the answer to this question only after I investigated my son’s homework (and other examples of assignments online). Kids are asked to sort facts from opinions and, without fail, every value claim is labeled as an opinion. Here’s a little test devised from questions available on fact vs. opinion worksheets online: are the following facts or opinions?

— Copying homework assignments is wrong.

— Cursing in school is inappropriate behavior.

— All men are created equal.

— It is worth sacrificing some personal liberties to protect our country from terrorism.

— It is wrong for people under the age of 21 to drink alcohol.

— Vegetarians are healthier than people who eat meat.

— Drug dealers belong in prison.

The answer? In each case, the worksheets categorize these claims as opinions. The explanation on offer is that each of these claims is a value claim and value claims are not facts. This is repeated ad nauseum: any claim with good, right, wrong, etc. is not a fact.

In summary, our public schools teach students that all claims are either facts or opinions and that all value and moral claims fall into the latter camp. The punchline: there are no moral facts. And if there are no moral facts, then there are no moral truths.

As Allan Bloom wrote 35 years ago at the beginning of The Closing of the American Mind:

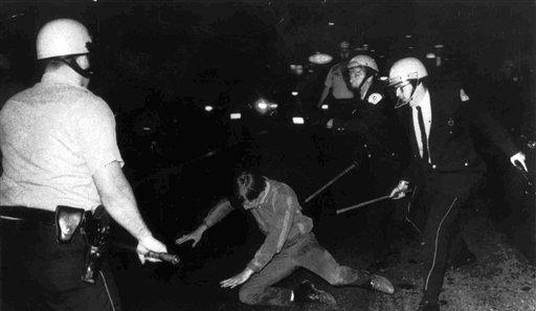

There is one thing a professor can be absolutely certain of: almost every student entering the university believes, or says he believes, that truth is relative. If this belief is put to the test, one can count on the students’ reaction: they will be uncomprehending. That anyone should regard the proposition as not self-evident astonishes them, as though he were calling into question 2 + 2 = 4. These are things you don’t think about. The students backgrounds are as various as America can provide. Some are religious, some atheists; some are to the Left, some to the Right; some intend to be scientists, some humanists or professionals or businessmen; some are poor, some rich. They are unified only in their relativism and in their allegiance to equality. They are unified only in their relativism and in their allegiance to equality. And the two are related in a moral intention. The relativity of truth is not a theoretical insight but a moral postulate, the condition of a free society, or so they see it. They have all been equipped with this framework early on, and it is the modern replacement for the inalienable natural rights that used to be the traditional American grounds for a free society. That it is a moral issue for students is revealed by the character of their response when challenged – a combination of disbelief and indignation: “Are you an absolutist?” the only alternative they know, uttered in the same tone as “Are you a monarchist?” or “Do you really believe in witches?” The danger they have been taught to fear from absolutism is not error but intolerance. Relativism is necessary to openness; and this is the virtue, the only virtue, which all primary education for more than fifty years has dedicated itself to inculcating. Openness—and the relativism that makes it the only plausible stance in the face of various claims to truth and the various ways of life and kinds of human beings—is the great insight of our times. The true believer is the real danger. The study of history and of culture teaches that all the world was mad in the past; men always thought they were right, and that led to wars, persecutions, slavery, xenophobia, racism and chauvinism. The point is not to correct the mistakes and really be right; rather it is not to think that you are right at all.

And as McBrayer’s essay today illustrates, that’s now a state-sanctioned policy. Because as Glenn Reynolds writes at Instapundit, “Our ruling class doesn’t like the idea of moral facts because that might limit their flexibility, which reduces opportunities for graft and self-aggrandizement.”

See also: Oceania’s existential struggle with Eastasia and/or Eurasia and the real-life turn-on-a-dime pivot by leftwing intellectuals that inspired it.

Earlier: ‘Let’s Destroy Liberal Academia’

Join the conversation as a VIP Member