The Kent State shootings hadn’t happened yet. Neither had Neil Armstrong’s moonwalk. President John F. Kennedy was four years gone, but Bobby was still alive. 1968 was both a clear precursor to the more sobering upheavals of 1969, and the last year with any tangible connection to 1967’s Summer of Love. Rock was in its psychedelic golden age, the Sgt. Pepper/Satanic Majesties era. “Light My Fire” was the counterculture’s national anthem. Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, and Brian Jones were still alive, and I had seen them all.

Napa High School — I was a junior that year — was not the epicenter of the growing subculture, but damn close. Only a chaparral-hilled 39 miles separated us from San Francisco. It was a journey I undertook every chance I got, but it was a night ride into neighboring Sonoma County that provided the heaviest musical impact that summer of 1968.

In Northern California, we had our own claim to aural infamy. Named after an ephiphanic admixture of Owlsey’s LSD, Blue Cheer, a band the critics mostly hated, had drilled its way to number 14 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart with a psychedelicized cover of Eddie Cochran’s “Summertime Blues.” The band’s debut album, “Vincebus Eruptum,” peaked at number 11 on the Billboard Top 200, largely on the strength of the blistering single.

Tickets to Blue Cheer’s early June “Bill Graham Presents” concert at Sonoma County Fairgrounds had sold out briskly, but I’d gotten in line at Napa’s only music store in plenty of time to snag a handful for a carload of my friends.

Though the band we were going to see was named after a hallucinogenic drug we’d dabbled in, the night of the concert our stash consisted only of Mexican weed and two bottles of the Southern Comfort Joplin had made famous. I was designated driver not because I had agreed to stay sober, but because I was the only one with a car. My aunt had willed me her old 1947 Dodge sedan; no seat belts, no headrests, a steel dashboard and hard-charging V-8 that meant no good business for a 16-year-old rock hound unleashed.

It fell to me that summer evening to make the rounds, picking up friends who exist today only in long-haired photos in musty high school yearbooks. Absorbing the usual admonitions from my mother and walking out the door, I remembered to grab my Polaroid camera.

Forty-nine years ago, the drive from Napa to Sonoma was distinctly a country drive, especially at night. Sudden curves wound through John Muir’s forests, and undulating threads dipped and fell over endless vineyards. On concert nights, it could be counted on that most if not all the traffic was headed west, towards Sonoma, the Wine Country’s biggest little city.

Once at the Fairgrounds, we found a parking space in the huge lot and tippled out the Southern Comfort in passed-around snorts. They wouldn’t let you in with a bottle. Our joints stashed in hideaway pockets (possession of marijuana was a serious offense in Sonoma County back then), we joined up with hundreds of other scruffy stoners thronging through the front doors of the exhibition hall. Walking in a tribal trance during the set of an opening band lost to memory, we sought out and found familiar faces from Napa. An intermission, some sneaky tokes, and Blue Cheer hit the stage.

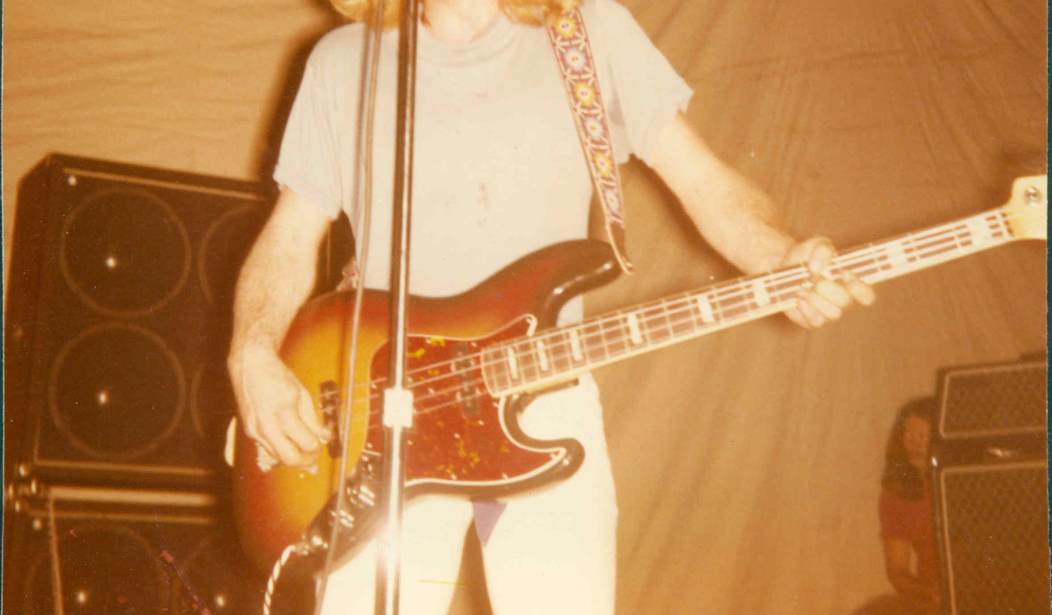

They led off with “Summertime Blues,” which thoroughly roused the house, and they ended up closing with their big hit too. In between, guitarist Leigh Stephens unleashed a whammy-bar shriek-fest, bassist Dickie Peterson laid a slab of white noise with his Precision Bass, and drummer Paul Whaley pounded everything together like a demented shaman.

I was transfixed of course, but not so much so that I forgot my camera. At what I thought were the perfect moments, I captured shots of each member of the band.

Sonoma’s finest would be on heightened alert, so we smoked down the last of the roaches and scoured the interior before I turned the key in auntie’s old warhorse. I started out driving a few blocks toward what I thought was the highway back to Napa, but somehow got turned around, and soon we were totally lost on an unfamiliar road with no shoulder leading in an unfamiliar direction out of the city.

Here’s the thing: when you get lost, and there is a good stretch of road in front of you, you tend to speed up, because you need to find somewhere to stop, turn around, and figure out where the hell you are. I was doing about fifty when I saw the barricades and blinking lights. Road Closed. Road Gone was more like it.

I slammed through — the Dodge bumper impervious as the barricade splintered — and my tires hit the kind of construction zone gravel and dirt that it is virtually impossible to regain control on.

The car fishtailed, careened sideways for 300 feet, throwing up a pall of dust. It did not tip over.

We sat soundlessly, dusty motes from an opened wind wing catching silver light from an overhead pole. There was a man out walking, a man who would have been just about the age of our parents. He cautiously approached the driver side window. I rolled it down.

“Everyone all right?” he asked, staring in at a group of half-wasted hippies with acute hearing loss, then walked off muttering as if we’d ruined his whole night.

I sobered up quickly and restarted the stalled engine. We found the road back to Napa, and I took it, with my friends, my aunt’s car, and my camera intact. The photos I took of Blue Cheer and sent to the band’s official website just before the Dickie Peterson’s 2009 death from cancer are still floating around the internet.

We arrived home late, having avoided what might have been a grisly roll-over accident and life-altering encounter with law enforcement, but something singular did happen that night. We couldn’t have known it then, because the genre had not been invented, but “Summertime Blues” and “Vincebus Eruptum” would ultimately receive credit as cornerstones in the invention of heavy metal. They are believed by many to be the first heavy metal records to chart.

We had witnessed a seminal moment in the birth of heavy metal. It seemed as if they played that song every hour for the rest of the summer.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member