WHEN THINGS GET SO BIG, I DON’T TRUST THEM AT ALL. YOU WANT SOME CONTROL, YOU’VE GOT TO KEEP IT SMALL: The triumph of bedroom pop. From Joe Meek to Taylor Swift: a short history of lo-fi.

I must have been about 16 when I got my first Portastudio. The compact home recording unit had first been introduced by Japanese electronics firm Teac in 1979, offering unprecedented multitrack dubbing to the bed-bound amateur musician. For a little less than $1,000, you could record four separate tracks of instrumentation — as much as the Beatles had when making Sgt. Pepper — on an ordinary cassette tape. By the time I got my teenage hands on a four-track machine of my own, that price had come down by an order of magnitude. It was a chunky little unit in pigeon blue with just two microphone sockets and a small handful of mixing dials for volume control and stereo panning. Anything you fed into it would be squashed and smudged into its limited dynamic range and smeared all over with a waterfall of tape hiss. But to me that little box was magic.

Recording music myself in the comfort of my bedroom made sound into something plastic. It gave me a sense of agency and allowed me to think in a different, more holistic, but also more experimental way. At that time, most of the songs in the charts and on the radio seemed to be made in big, expensive studios with mixing boards that looked as though they could launch a space shuttle, by highly paid producers wielding microphones that cost, individually, more than everything I owned put together. My friends and I were grabbing beats from the presets on toy Casio keyboards, plugging our guitars directly into the Portastudio jack inputs, then turning the tape over so the sound would play backwards, looping the signal from a daisy chain of cheap effects boxes until it fed back a sound that fooled my friend Marc’s older brother into thinking we had a Moog synthesizer. We bought records by artists with an aesthetic (almost) as scrappy as our own, poring over the badly photocopied sleeves of short-run CDs issued by micro-labels in Nottingham, Wetherby and Olympia, Washington. Never would I have imagined that scarcely more than two decades later, some of the biggest pop stars on the planet would be embracing lo-fi aesthetics and making records in their bedrooms just like us.

To be fair, people are making records on laptops in their bedrooms these days, because digital audio workstation (DAW) software is ubiquitous, and as such, it’s done much to kill the traditional recording studio. Also, it’s much cheaper for an artist to rent a real studio to bring the band in to record the drum tracks, and then everything else can be edited and overdubbed at home, in a small project studio, or a bedroom with some decent acoustic treatment on the walls.

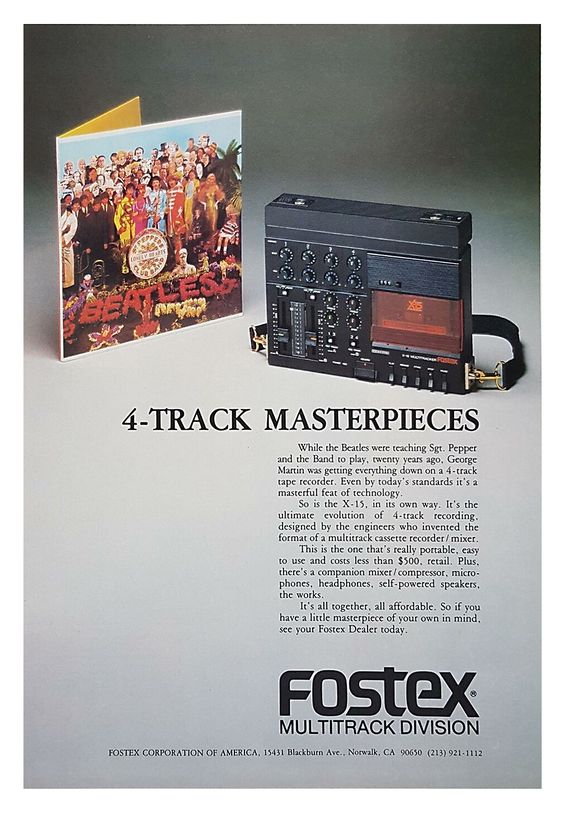

And the notion that “For a little less than $1,000, you could record four separate tracks of instrumentation — as much as the Beatles had when making Sgt. Pepper — on an ordinary cassette tape,” isn’t quite true. I’m surprised that Fostex never got sued for false claims for this mid-’80s ad:

Sure you can make the next Sgt. Pepper — you just need John, Paul, George, Ringo, George Martin, and engineer Geoff Emerick, and plonk them down into one of the best equipped recording studios in the world. And hire plenty of sidemen to play the exotic instruments that the Fab Four couldn’t. And an orchestra for the finale. Oh, and ditch the hissy cassette four-track which jams all those tracks onto a 1/8th” wide audio cassette, and invest in a few Studer J-37 reel-to-reel machines, which spreads the four tracks over one-inch-wide tape for infinitely greater fidelity. And noticed I said “a few.” Martin and his engineers used two J-37s synced together to record the massive orchestral overdubs on Pepper’s closing track, “A Day in the Life.” There was also an additional reel-to-reel recorder that ran when mixing to create the Beatles’ famous Artificial Double-Tracking (ADT) effect on many of their lead vocals. But hey, other all of that, you’re good to go with a portable Fostex X-15 cassette recorder!

To be fair though, the impact of the cassette four-tracks of the 1980s was long-lasting: it democratized music recording and songwriting; and it’s not a coincidence that several of us early bloggers had our roots tinkering in that earlier DIY-era.

Speaking of which, classical reference in headline: